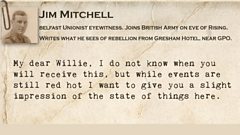

Jim Mitchell

Unionist witness to the Rising

James 'Jim' Mitchell was born in Belfast in the late 1870s. At the time of the 1911 Census of Ireland, he was living in East Belfast with his father, two brothers and his sister, and working as a National School Teacher. He also taught at Belfast Metropolitan College.

I can hear the phit phit of the bullets singing through the air

Mitchell opposed Home Rule, signing the Ulster Covenant alongside his father and brother, Joseph, in 1912.

In April 1916, he took the decision to travel to Dublin with Joseph, to join the British Army:

"Joe and I arrived on Sat. evening and dined with the Adjutant, afterwards going to the Theatre Royal to see Wilkie Bard. We were in the Officers' Mess until 3 am on Sunday, and Morgan made arrangements to have me put through all the tests on Sunday morning at 11.30.

Result - I became a Soldier of the King on Easter Sunday.

Since then we have been through some experiences ..."

Unable to get out of the city, Jim Mitchell went on to have an eventful week. Staying at the Gresham Hotel, his was a close-up experience of the Easter Rising from the heart of Dublin. He recorded this in two long, very vivid letters, often in the moment, writing he says to give an impression of the happenings "while events are still red hot."

Easter week 1916

Start of the Rising

After completing "all the tests" on Easter Sunday, Mitchell celebrated his new military status by lunching in the Officers' Mess. Next day, Easter Monday, he made for the races with a friend: "...we went out to Fairyhouse Races. All came home with a pound or two extra in pocket. While out there we heard rumours of trouble with the Sinn Feiners in the City and naturally these stories did not lose in the passing round."

"Coming home by train, however, we soon experienced a few evidences of the storm. The train stopped 3 miles outside roadstone and all had to walk into the city, as a bridge over the railway line had been partially destroyed."

Mitchell eventually reached the Gresham Hotel on foot. Venturing out on Monday night, he was met with "some ghastly sights."

"Two horses lay dead opposite the Hammam, their soldier riders having been shot dead and carried into the hotel. Human blood covered the footway. All military and police were confined to barracks, and the mob had complete possession of the principal thoroughfares."

"I saw the looting of 12 shops, all being wiped out in a marvellously short time. When the vanguard of the mob smashed in the windows of the shops, the numbers behind so pressed on them that the former got the full benefit of the falling plate glass. What faces and hands had men, boys, and women who were unlucky enough to be pressed into the gaping fissure. Blood, blood everywhere."

Comparatively quiet

Tuesday proves comparatively quiet. Venturing out, Mitchell says "no military nor police could be seen", and with looting continuing, Mitchell decides to return to the hotel.

After this, he says that "no one in the hotel, except a few of the staff, has shown a nose outside the door."

Bombardment

At 1am on Wednesday morning, Mitchell says "the fusillade began", and after finally getting to sleep at 5am, he is woken at 8am by "a terrific rattling and roaring".

"Later we were informed this was caused by the bombarding of Liberty Hall, the headquarters of all the trouble and disaffection... We are practically prisoners in this building ... the machine guns and rifles are busy at it, and as I write here in the front of the building I can hear the phit phit of the bullets singing through the air ..."

"Twenty minutes later. An exceptionally loud roaring and rattling brought everyone to his feet ... A boat of some kind is at O'Connell Bridge and is evidently the cause of the loud reverberations. What these mean I know not, as no result is, as I said, apparent. What I do know is that I have got a damned fine reception into the Army, and that the salute of guns is irreproachable ..."

Three days after signing up for the British Army, he says he cannot get to his base:

"When and how I reach the barracks is wrapt in mystery ... Acrid smoke is penetrating into the rooms ..."

Out of an upstairs window, he sees a difficult sight: "One or two people were in the street, and I happened to glance at one man in shirt-sleeves. I heard a shot, drew back, and immediately popped my head out again just to see the man drop. Two of the others carried him off. This is the first person I have ever seen killed, and my feelings could be imagined ..."

He sees buildings ablaze: "as these shops were in the same block, things looked serious for us." Mitchell says the Fire station refuses to send out a brigade, as one of their firemen had been shot on Wednesday answering a call, but they are later reassured that the Brigade was at the fire.

A Terrific Roar

On Thursday, Mitchell gets word that Portobello Barracks, which he had been speculating on how to reach, is under attack, and that "the position there is serious ..."

An early dinner is had at the hotel, as "after dinner all were to clear out of the front rooms as the military intended to clear Sackville St of all snipers, and to bombard the GPO. Blinds were drawn and shutters put up. While at a game of solo there was a terrific roar ... shots had come from a field 18 pounder placed in a street just above our hotel ..."

These leave the building that was hit, the YMCA, with "a big ugly hole"; and others carry away "the whole top" of another building, plus "huge slices" of another. "What a sight the YMCA presented! Similar to a scene in one of the shelled towns in France."

As they are taking dinner, "an armoured car passed slowly down Sackville St." An officer from it tells them they have to leave the front rooms, and go to the back or basement of the hotel, "as the GPO was about to be shelled from the street, just opposite to our building."

Thereafter, he says, they spend the evening in the Aberdeen Hall supper room: "Cards were played by candlelight until 5am people sleeping or attempting to ... going upstairs in the dawn we had a peep out and discovered that the GPO was on fire."

Effects on the men

Mitchell reflects on the effects of the experiences to this point: "We had now come to look upon all these happenings in a matter of fact way. The abnormal has become normal. I reflect, after seeing the dead, men and horses, in the street that anything must happen and should happen to save the state."

"... One becomes convinced by the necessity of 'one for all and all for the State'. Any man who passively or actively denies this truth becomes as the rat, vermin and should be destroyed as such. I felt relief and secretly exulted at the inglorious end of the creatures with such mean and selfish minds."

Feeling trapped by the company of those at the hotel, on Friday Mitchell "lay until 4pm", and describes how he and his friends have set about passing time:

"One could scarcely believe that such craven fear existed in the minds of those who call themselves men. This fear has proved extremely useful, as it has afforded the almost entire comedy of our imprisonment. We take delight in the signs of terror in the faces of some of the mere males, and allow no opportunity to evoke them pass."

"We rattle chairs in the darkness, drop tin boxes and bang tables, for the pleasure of seeing some of them scuttle away to the safety of an improvised dug out or the security of a room far from the roof. A few seek courage in quaffing innumerable strong liquors and the result is almost nervous collapse."

That night, they "played solo whilst almost to stupefaction. Snipers still being sniped, and rattling going on ad infinitum ..."

Beginning of the end

Retiring in the early hours of Saturday, Mitchell says "we saw an awe-inspiring spectacle ... the whole of the GPO block of buildings for a couple of hundred yards was a mass of flame ..."

That day, they are "hunted from our bedrooms to the ground floor and compelled to keep to the safety of the lower rooms". Suspecting flash signalling to snipers, the military warn that anyone "appearing at a window after this warning was to be shot at ..."

Despite this, before dinner, Mitchell and a friend surreptitiously open a window, and see "a group made up of soldiers with drawn bayonets in their rifles, and of worn looking prisoners in mufti. This looked to be the beginning of the end."

Sees the rebels surrender

So it proved, as Mitchell later witnesses the surrenders in Sackville Street: "That [Saturday] evening, at early dinner time, we witnessed the surrender of about 500 Sinn Fein troops, who delivered up their arms to the military almost opposite our hotel ... a long procession of men fully armed passed by in single file. That was the first section of a large number of Sinn Feiners, who were headed by one in green uniform and slouch hat and holding up a white flag."

"They were advancing to the commander of the military in Sackville Street to throw down their arms in token of surrender. No guard accompanied them, and it was not until they were surrounded by the soldiers and had divested themselves of all arms and ammunition that they became prisoners."

"... Before the prisoners were marched off, the Sinn Feiners were formed up two deep, and their names were taken down in note books."

From the roof, looking across Dublin, Mitchell sees "the majestic sight of the great fires ... the conflagration was awe inspiring. The whole of the city seemed as if doomed ... the noise of falling roofs and walls gave an added horror ..."

After the Rising

Leaving the hotel

Finally able to get out of the hotel again, Mitchell surveyed the damaged city on Sunday 30 April:

"Later in the day we were able to reach O'Connell Bridge. Then we realized for the first time the fearful havoc wrought by fire and artillery during the week ... Round along Eden Quay for about 200 yards the houses are in ruins. In all this area there exists nothing but smouldering masses of bricks, out of which shoot occasionally tongues of flame ... the GPO is an empty shell ... for apparently unending distances stand gaunt wrecks of former great establishments ..."

On Monday 1 May, Mitchell goes further afield in the city: "streets crowded with civilians ... the scene was animated ... Stephen's Green itself was deserted ... It presented, however, a picture of rare beauty, the early spring green of the trees and shrubs lending a beautiful and delicate contrast to the marks of destruction all around."

He finds travel is still forbidden: "no one can leave the city yet, and when this allowed, all wishing to travel must first procure a military pass."

This results in some of the hotel's inhabitants having concerns which Mitchell finds amusing. Himself believing they should "be on their knees with thankfulness for their fortunate circumstances during the dangerous crisis", instead:

"... one cheerily optimistic lady wants to know if the dance previously arranged for Wednesday next will come off, and how those who had already bought tickets will be able to reach and depart from the Aberdeen Hall ... Conceive of it, dancing with the scenes of horror and destruction all around us, and before the mind's eye continually. What minds must some people possess!"

Stuck in Dublin

On Tuesday, 2nd May, Mitchell sees friends off to Belfast. He and others "wished to report ourselves as early as possible", but are advised that "as the barracks were full up with soldiers ... to stay in the hotel for a day or two."

He does so, and on Wednesday hears from a friend that their Colonel, learning of their circumstances:

"... generously signed passes, and granted us leave until Tuesday next. What a glorious effect this news had on Alex and myself ... The prospect of seeing our people again and of obtaining clean fresh clothes again, and of course money, was exhilarating."

Home to Belfast

On the Thursday after Easter week, Mitchell was finally able to leave Dublin, having seen "an inspection of our Battalion by Sir John Maxwell this morning at Portobello Bks ... spoke to the troops for quite a while." Mitchell reached home late that afternoon:

"At home in Belfast! All our experiences seem now to be those of a dream. Everything that has passed within the past 12 days has the impression of unreality, and I suppose it will be days before the events and incidents attain their true perspective."

"... And now to bed and sweet repose."

Later life

Following the Rising, Army records indicate that Mitchell became a Lieutenant in the Royal Army Service Corps, with his first theatre of war being Mesopotamia in 1917.

These pages are based on personal testimonies and contemporaneous accounts. They reflect how people saw things at that time and are not meant to be a definitive history of the period.

The words of Jim Mitchell

Voices 16 objects

Voices 16 galleries

Credits

Jim Mitchell's account is reproduced with the kind permission of the .

Jim Mitchell's image is reproduced with the kind permission of the .

Additional thanks to Dr Éamon Phoenix.