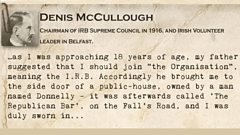

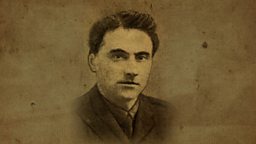

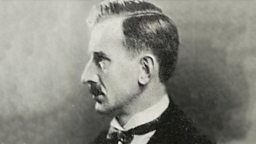

Denis McCullough

Orders for Belfast

From Belfast's Divis Street, Denis McCullough was "in continuous control of the IRB [Irish Republican Brotherhood] in Belfast and indeed in Ulster" in the years before 1916.

My allegiance was to the I.R.B. first and last

Chairman of the Supreme Council of the IRB at the time of the Easter Rising, and of the Volunteers in Belfast, he was determined that "if the Rising was coming off on Easter Sunday, I couldn't be out of it, that I would bring my men out to Tyrone ..."

He did so, but confusion resulted, and McCullough and his men eventually played no active fighting role in the Rising. He was arrested and imprisoned shortly afterwards.

Nationalist background

Denis McCullough was born in Belfast in 1883, being he says "brought up in a Nationalist and Separatist atmosphere." His father and grandfather were both involved in the Fenian movement. He himself joined Cumann na Gael and the Tir na n-Og branch of the Gaelic League, and his own family home "was a meeting place for the I.R.B."

When McCullough was just shy of 18, his father suggested that "I should join 'the Organisation', meaning the I.R.B." Sworn in at "the side door of a public house" he was unimpressed by many of the IRB's senior members, and immediately set about introducing his own changes:

"I was disappointed and shocked by the whole surroundings of this, to me, very important event and by the type of men I found controlling the Organisation; they were mostly effete and many of them addicted to drink. In a year or two, after I had organised one or two new Circles of young men to support me, I got most of these older men retired out of the organisation, which had been split up into about three factions ..."

Subsequently, he says, "I was elected a member of the Supreme Council [of the IRB], representing Ulster ..." and would remain so until the Rising in 1916. He believed "Belfast was one of the vital and continuing centres of the I.R.B."

Dungannon clubs

With Bulmer Hobson, McCullough co-founded the non-sectarian Dungannon Clubs. The Manifesto for these he recalled as being written by Hobson, who "set out as our first and final objective 'The establishment of a "Free and Independent Republic" for Ireland'." This description he says he had to be argued into, thinking it "would destroy the value of the movement as a cover for the I.R.B. in which the real work for a Republic could be done ..."

The Dungannon Clubs' main activities, he says, included publishing pamphlets and a newspaper, The Republic. They held meetings and debates, and "concerned themselves particularly with an anti-recruiting campaign which they carried on by means of our outdoor meetings, the postcards and particularly the pamphlets ..."

Branches were established "in several parts of Ireland, several in County Tyrone and in County Derry, also in London and Glasgow. They were of considerable value in keeping the nationalist-Separatist spirit alive ..."

They then became one of the organisations, McCullough says, which amalgamated to result in "the foundation of 'The Sinn Fein League'."

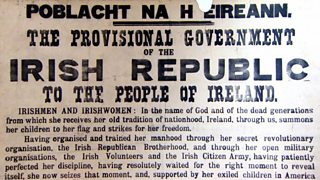

Irish Volunteers

McCullough recalls being heavily involved in the organisation of the Irish Volunteers in Belfast. This was, he says, because the IRB leaders in Dublin "took great care to see that control was kept in the right hands ... I immediately proceeded to organise the Irish Volunteers in Belfast, getting my own men, mostly trained in the Fianna, into key positions ..."

" ...the Irish Volunteers swept nationalist Belfast into its ranks and by the time war broke out, in 1914, we had over 4,000 men in the ranks."

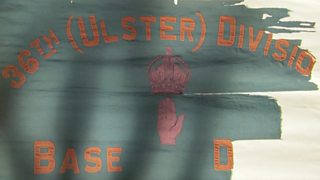

Elected as Chairman of the Volunteer Committee in Belfast and surrounding districts, McCullough was eager to keep the ranks together. However, at the urging of the Irish Parliamentary Party, he says many nationalists left to fight in World War One, and "the Volunteers were split and of the four thousand enrolled men ... we were left with less than one hundred and fifty all told ..."

Divided into sections the remaining men drilled regularly on the side of Divis Mountain, says McCullough, while "On special occasions, such as the visit of Padraig Pearse to lecture in St. Mary's Hall ... we mobilised our full force ..."

Imprisonment in 1915

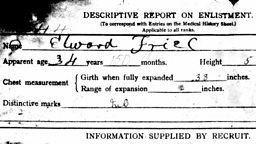

In 1915, McCullough received a Deportation Order from the "competent Military Authority" in Belfast, along with Herbert Moore Pim and Ernest Blythe. Debate ensued, he says, about the response and Eoin MacNeill proposed that one person should be sent to America to do propaganda work.

McCullough recalls being nominated to go, but "categorically refused to leave the country."

He was then arrested, tried and sentenced to four months imprisonment in Belfast Gaol, being released in November 1915.

Chair of IRB Supreme Council

Following his release, McCullough's name was proposed for the position of the Chairman of the Supreme Council of the IRB. He himself had "intended to propose Pearse as Chairman for the coming term", but says Sean McDermott "asked me 'for God's sake' to do nothing of the kind, as 'we don't know Pearse well enough, and couldn't control him' - an important factor then."

McCullough says he was reluctant: "I protested that I did not think I was a suitable man for the position; I did not wish the responsibility and in any event I resided in Belfast... My protests were overborne and, despite them, I was elected unanimously as Chairman and occupied the position up to the Rising."

Rising plans

McCullough was present, he says, at the IRB Supreme Council meeting when "the question of a Rising out was discussed and decided. I know that I was in the chair ..." After discussion, "the unanimous decision arrived at was that preparations for a Rising were to be pushed forward and a date arranged in any of the three following contingencies, viz.

- Any attempt at a general arrest of Volunteers, especially the leaders.

- Any attempt to enforce conscription on our people.

- If an early termination of the war appeared likely."

It was decided "to set up a Military Committee to take charge of the preparations and plans. McDermott, Pearse, Ceannt, Plunkett and Connolly were appointed to this Military Committee, there and then ..."

Orders for Belfast

McCullough is summoned to Dublin to a meeting where “Pearse made the following arrangements. When the date for the Rising was decided, we were to receive a code message …. I was to mobilise my men, with all arms and ammunition and equipment available, to convey them to Tyrone, join the Tyrone men mobilised there and "proceed with all possible haste, to join Mellows in Connaught and act under his command there".”

McCullough "pointed out the length of the journey we had to take, the type of country and population we had to pass through and how sparsely armed my men were."

But, he says, "Connolly got quite cross at this suggestion and almost shouted at me 'You will fire no shot in Ulster: you will proceed with all possible speed to join Mellows in Connaught, and', he added, 'if we win through, we will then deal with Ulster'. He added further, to both [Frank] Burke and myself 'You will observe that as an order and obey it strictly'."

As far as McCullough was concerned, he says he had now "got my orders for Belfast, direct from Pearse and Connolly."

Waiting

McCullough, now "awaiting the code message giving me the date of the Rising", begins "making all preparations possible to carry out my orders."

Meanwhile, on the Sunday before Easter week, he attends a Volunteer function. As he arrived, Bulmer Hobson was speaking, and "to my amazement I heard him advocating a policy of waiting; that this was not Ireland's opportunity and that a more favourable time would come later."

"...to me it sounded like bedlam. I had just left Tom Clarke, who told me the Rising was fixed for the following Sunday and here was the Secretary of the Irish Volunteers advocating publicly, a policy of delay."

Ready for action

After receiving no further orders regarding the Rising, McCullough "was very concerned myself that no instructions had reached me and could not understand it." Finding Sean McDermott in Dublin on the Monday before the Rising, he says he "locked the door and told him that he must talk to me."

McDermott told him "of the plans for Dublin and of the coming of the German arms to Clare or Kerry. He also said that they expected a ship to Dublin, with German officers to lead the Rising."

McCullough found it "hard to believe", but swore his loyalty: "that if the Rising was coming off on Easter Sunday, I couldn't be out of it, that I would bring my men out to Tyrone if possible, and carry out the orders I had already received from Pearse and Connolly."

He then "returned to Belfast on Tuesday of Holy Week and proceeded with my arrangements ..."

Later, reflecting on his own lack of information, McCullough says, "I have no complaint ... A rising had been decided on. The fewer who were aware of the arrangements, the less chance there was of any leakage of information. Too much had been lost in previous attempts by too many people knowing and hearing too much."

Easter Week 1916

Preparations complete

By Good Friday morning, McCullough says he had made all of his necessary arrangements. He had "proceeded with my arrangements to get my men mobilised; to get them equipped, as far as our money would go and to make arrangements to get them out of Belfast, for the manoeuvres, as quietly as possible."

By trade in the piano and music industry, McCullough had also "made various personal arrangements, such as getting an Attorney to complete a Deed of Assignment of my business to my mother, certain arrangements for its continuance, the payment of creditors and members of the staff."

Orders were orders

Then, with the Volunteers arranged to leave Belfast by rail for mobilisation at Coalisland, Co. Tyrone, McCullough says he was called to a meeting on Good Friday morning near Carrickmore. Various Tyrone leaders were in attendance, he says, including Dr Patrick McCartan, [Frank] Burke, Father Daly and Father Coyle, and they heard of the Easter Sunday plans.

McCullough says: "They expressed the opinion – particularly the priests but also Burke – that the whole thing was engineered and inspired by Connolly; that it was not a Volunteer, but a Socialist Rising; that it had no sanction etc. from MacNeill."

In response, McCullough goes on, "I stated specifically that my allegiance was to the IRB first and last; that I was satisfied that the proposed Rising was inspired and would be directed by the IRB through its leaders in the Volunteers, with Connolly and the Irish Citizen Army, an integral part of any fighting force that would turn out; that I was taking my orders from the IRB through its Military Committee and that accordingly I was in Tyrone and was bringing my men to Tyrone, to carry out the orders I had received from Pearse and Connolly."

He urged, he says, those gathered to mobilise their men and prepared for Sunday, but found "they ridiculed the idea of a march to Connaught, pointing out the difficulties, almost the impossibility of such a march, mostly through very hostile territory. I agreed that I was aware of these difficulties, but orders were orders ..."

As those gathered "wouldn’t take my assurances for the fact, that it was an IRB not a Connolly Rising", it is decided, McCullough says, to send messengers to Dublin to "verify the position."

Discussions and arguments

On Easter Saturday, McCullough says, the messengers "reported that the position was substantially as I had outlined it", but "the discussion and arguments began all over again”, and across the day "no progress was made towards a decision."

Later, McCullough locally sorts practical arrangements for his men at Coalisland, after which, he recalls, back at Carrickmore and examining his automatic, he "was fool enough to pull the trigger to ascertain if it was loaded – it was, and the bullet went through my left hand, breaking no bones ... I suppose I must have passed out, because I came to, sometime later, lying on the side of the ditch."

After he sleeps and is treated, the "discussions and arguments were resumed", McCullough says, "with no better results."

An ultimatum

By Easter Saturday evening, with his men arriving to Coalisland, McCullough says he was "worn out and getting into despair."

Having made some local visits, "nowhere did I find any sign of activity." Believing the arguments are "going round in circles", McCullough says he now "issued an ultimatum" to the Tyrone leaders present: "that if they would not undertake to get their men moving and ready to start with mine for Connaught in the morning I would order my men back to Belfast and disband them there."

In response, McCullough says, "the Tyrone leaders stated that they would bring their men out, but would remain in their own districts."

To him, "I could see no usefulness in action of that kind and as it made no provision for the hundred or so odd men and boys that I had brought to Tyrone, in accordance with my orders, with only two days' rations each ... my only alternative was to bring them back to Belfast."

Subsequently, after midnight, he says he gets a messenger to Coalisland to order his men to be ready to march next morning, and after some more "fruitless discussions", McCullough recalls he "went to bed, worn out in mind and body."

Return to Belfast

Next day, Easter Sunday, McCullough says he met with his Section leaders at Coalisland to explain his decision that the men should return to Belfast.

"Some of them demurred, but I insisted on my authority, and ordered them to get their men on the road to Cookstown, the only station in Tyrone from which a train left for Belfast, on that day."

He says that "throughout the days I was in Tyrone, the responsibility for the lives of those I had with me, weighed heavily on me. A number of them were married men with families and the greater number were young men and boys, for whose lives and liberty I would be held responsible."

McCullough recalls that he got the men "started back for their homes, with orders to demobilise there and be ready in case any further orders came for them."

He himself, he recollects, initially planned to carry on to Dublin with Dr McCartan. They try to reach Portadown by car, there to catch the Dublin train, but the car breaks down. He says that with repairs not possible "in time to enable us to get the train at Portadown, I decided immediately to follow the men and try to overtake them on their march to Cookstown."

Stewartstown Incident

After catching up with his men, McCullough says an incident happened at the village of Stewartstown. This followed the arrival of "a man named Butler, who was kind of a hanger-on to the Volunteers before the split, but had no connection with us afterwards, apparently came from or his wife came from Coalisland and was there for the Easter holidays when our men arrived ... On Sunday morning he was the worse of drink and tailed on to the Column, on its march to Cookstown."

While passing through the village of Stewartstown – which McCullough refers to as "a hotbed of Orangeism" – he says a "crowd of the inhabitants attacked the column and it took all my efforts to keep them steady and from retaliating. I got them safely through Stewartstown, but Butler, who was in the rear, turned back and fired a shot or two at the Orange crowd, from an old revolver he carried."

Butler, he says, is arrested and some of the Volunteers "broke rank and proceeded to stage a rescue." McCullough says he "got between them and the police and with the help of one or two of the Volunteer officers, got them to re-form ranks and continue their march."

McCullough says: "If I had permitted a fracas to develop, undoubtedly some of our men would have used the revolvers or automatics they still had and the whole affair would have developed into a sectarian riot, to the disadvantage and disgrace of the whole movement."

He continues: "If we had been able to get the Volunteers started on the march on Connaught, as ordered by Pearse and Connolly, I have no doubt now that the scenes similar to that at Stewartstown would have developed at every Protestant village or townland we passed through, in Tyrone and Fermanagh, before we got to the Connaught border, and that we could not have avoided a fight, somewhere along the way."

After the Rising

Arrest and imprisonment

Upon reaching Belfast, McCullough says "the men dispersed to their homes."

He himself is eventually arrested at home, as are a number of other Volunteers.

McCullough says he was first lodged in Belfast Gaol, and then sent by train to Dublin under guard, where "every second house, coming in, seemed to have a Union Jack flying and where I only saw about half-a-dozen friendly looks."

Kept in Richmond Barracks, McCullough says he met with Sean McDermott for the last time:

"...I was in the room opposite the one in which Sean McDermott was lodged. I met him on the landing, being brought out after his court-martial. He embraced me, said "his number was up" and bade me good-bye. We heard the shots that killed him the following morning and on the other mornings, when the other men were shot."

McCullough was next deported to Knutsford prison. He was subsequently transferred to Frongoch internment camp and finally to Reading Gaol.

Appeal and release

Following the Rising, McCullough recalls, a Commission was appointed by Parliament, and "... the Home Secretary ... had promised Parliament that any person recommended for release by this Commission, would be released."

McCullough says that eventually, when it appeared inevitable that "all would be brought before the Commission ... we mobilised the men, warned them that this might be used as a means of getting information about various leaders throughout the country, who had so far slipped through their fingers. They were instructed, therefore, that each man could say what he liked about his own actions and movements, but under no circumstance was he to mention any other man's name or give any information whatever about any other person’s actions or movements ..."

When he himself is called before the Commission, McCullough says: "They asked me particularly about my visits to Tyrone and I told them my business took me there regularly, and gave the best answers I could, on other matters."

McCullough says, that "the Commission, I believe, recommended my release", and this takes place in August 1916.

He concludes his recollections by saying that after the Rising: "... and the subsequent re-forming of the Volunteers and their translation into the I.R.A., on the formation of the First Dail, I could see no further use for the I.R.B. and severed my connection with it."

These pages are based on personal testimonies and contemporaneous accounts. They reflect how people saw things at that time and are not meant to be a definitive history of the period.

The words of Denis McCullough

Voices 16 objects

Voices 16 galleries

Credits

Denis McCullough's account is taken from his Witness Statements, reproduced courtesy of the .

Image courtesy of the .