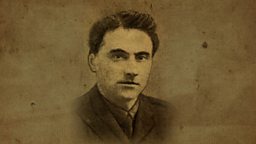

Margaret Skinnider

Teacher, suffragist, rebel

Margaret Skinnider was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1893 to immigrant Irish parents. As a young girl, Margaret spent many summers in Monaghan. Seeing "the fine places of the rich English people" contrasting with "the small and poor homes of the Irish", she says she began "to feel resentment, though I was only a child."

Scotland is my home, but Ireland my country

At home in Scotland, she became a maths teacher and was active in the women's suffrage movement. She joined the Glasgow branches of the Irish Volunteers and Cumann na mBan ('League of Women'). She also joined a women’s rifle club and proved a first class shot.

"In Glasgow I belonged to the Irish Volunteers and to the Cumann na mBan ... I had learned to shoot in one of the rifle practice clubs which the British organised so that women could help in the defence of the Empire ... I kept on till I was a good marksman."

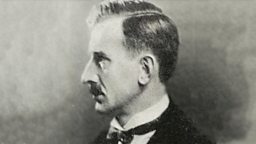

Invitation from the Countess

Invited to Dublin at Christmas 1915 by Countess Markievicz due to her reputation in Cumann na mBan, Skinnider did not arrive with standard luggage. "In my hat I was carrying to Ireland detonators for bombs, and the wires were wrapped around me under my coat."

Once in Dublin, she used her abilities in maths to draw up a map pinpointing locations to target with explosions. James Connolly confirmed, according to Skinnider, "that my map was correct and believed the plan practicable enough to carry out ... From that day I was taken into the confidence of the leaders of the movement for making Ireland a republic."

Boyish looks

Despite being in her early 20s, Skinnider also participated in excursions organised by Fianna Éireann, which she describes "an organisation that would do something for Irish spirit in Irish boys."

"When I told Madam I could pass as a boy, even if it came to wrestling or whistling, she tried me out by putting me into a boy's suit, a Fianna uniform. She placed me under the care of one of her boys ... she wanted to find whether I could escape detection."

Back to porridge

"When I left Dublin to return to my teaching in Glasgow, they made me promise that I would come back whenever they sent for me, probably just before Easter ... it was not easy to go quietly back to teaching mathematics."

Returns for the Rising

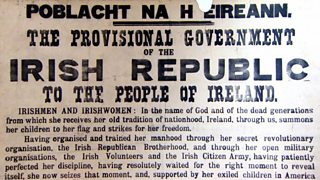

Skinnider returned to Dublin before Easter on Holy Thursday 1916, prepared to take action in support of her beliefs: "I joined the [Irish] Citizen Army, in Easter Week."

"I believed the time was at hand to do something. We all believed that, for an English war is always the signal for an Irish rising."

Easter week 1916

Preparations (Fri, 21 April)

On Good Friday, Skinnider was sent to Belfast in order to escort James Connolly’s wife and two of his children to Dublin – "they were to be there during the Rising."

Once back in Dublin, Skinnider began 'ammunition work', retrieving dynamite and bombs from their hiding places.

Flying the flag (Mon, 24 April)

With the Rising underway, Skinnider was sent to scout for St Stephen’s Green Command – "I was only a girl on a bicycle … it was a great moment for me. … At last all the men were standing ready, awaiting the signal. In every part of Dublin similar small groups were waiting for the hour to strike. The revolution had begun!"

She saw the tricolour raised above the GPO as the rebel troops occupied the building, then delivered another flag to be hoisted atop the College of Surgeons, "a small one I had brought on my bicycle from headquarters. ... We were all happy that night."

A narrow escape (Tues, 25 April)

Thrust into the heat of the battle, Skinnider experienced her "first taste of the risks of street fighting. Soldiers on top of the Hotel Shelbourne aimed their machine gun directly at me. Bullets struck the wooden rim of my bicycle wheels, puncturing it."

"I knew one might strike me at any moment, so I rode as fast as I could. My speed saved my life."

Female fighter (Wed, 26 April)

Wanting to be more involved in the fighting, Skinnider argues with Commandant Mallin – "we had the same right to risk our lives as the men … in the constitution of the Irish Republic, women were on an equality with men."

Mallin aquiesced, and Skinnider was given a uniform of green moleskin and "assigned a loophole through which to shoot … it was good to be in action. … More than once I saw the man I aimed at fall."

Shot and wounded (Wed, 26 April)

On a mission to burn buildings, Skinnider was shot. "'It's all over', I muttered, as I felt myself falling."

She contracted pneumonia while being treated, and her recovery was further hampered by a doctor who “made the mistake of using too much corrosive sublimate on my wounds, and for once I knew what torture is. The mistake took all the skin off my side and back."

She lay ill in the College of Surgeons for four days, nursed by Countess Markievicz.

Reluctant surrender (Sun, 30 April)

Word was delivered by despatch that a general surrender has been decided on. Markievicz "begged the Commandant, who could make the decision for our division, not to think of giving in. It would be better, she said, for all of us to be killed at our posts."

"He [Commandant Mallin] must have decided to give in at once, for in less than an hour an ambulance came to take me to St Vincent’s Hospital … I urged them again and again to hold out."

After the Rising

Shock at executions

Skinnider is astounded at the execution of the Rising's leaders. "Despite all our wrongs and their injustices, I did not dream of their killing prisoners of war."

Her shock deepened when she was visited in hospital by Mallin's widow and the Connolly sisters. "It is not the same thing to read of executions and sentences in the press and to hear of them from the lips of friends – the wives, mothers, and daughters of the men executed."

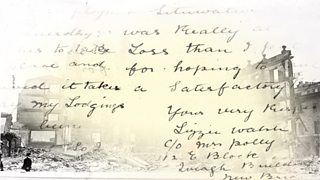

Return to Scotland

After having previously been deemed not well enough to be transferred from hospital to prison, Skinnider was discharged and granted a permit to travel to Scotland.

"I was proud that I could tell my mother I had been mentioned three times for bravery in dispatches sent to headquarters … I was given an Irish cross. This was the joint gift of the Cumann na mBan girls and the Irish Volunteers of Glasgow."

Committment to the cause

"When I went back to Dublin in August, it was to find that almost everyone on the streets was wearing republican colours. The feeling was bitter, too … even the children of Ireland have become republicans."

During the War of Independence, Skinnider returned to Ireland and trained Volunteer recruits. She was incarcerated during the Civil War, but later secured a teaching post in Dublin and campaigned for many years for equal pay and status for women teachers.

Final reflections

"For a long time after the rising, I dreamed every night about it. The dream was not as it actually took place, for the streets were different and the strategic plans changed, while the outcome was always successful. My awakening was a bitter disappointment, yet the memory of our failure is a greater memory than many of us ever dared to hope."

Margaret Skinnider died on 11 October 1971.

These pages are based on personal testimonies and contemporaneous accounts. They reflect how people saw things at that time and are not meant to be a definitive history of the period.

The words of Margaret Skinnider

Voices 16 objects

Voices 16 galleries

Credits

Margaret Skinnider's personal account is taken from the book Doing My Bit For Ireland, by Margaret Skinnider.

Additional information comes from her Military Service Pension file (Skinnider MSP_3 WMSP34REF1991), courtesy of the .

Thanks to Janet Wilkinson for assistance with Margaret Skinnider's testimony.

Image courtesy of the Seamus Reader Collection.