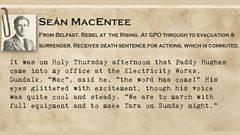

Seán MacEntee

Irish Volunteer from Belfast

Seán MacEntee was an Irish Volunteer from Belfast who came from a strongly nationalist, middle class Catholic business family. Disillusioned by the direction of parliamentary Home Rule, and coming to believe that the circumstances of World War One provided the opportunity for other actions, he went on to fight in the 1916 Rising.

One felt a free man ... we were soldiers of the free Irish nation

Ordered to bring the Rising orders from Patrick Pearse north, he was with the Volunteers at Castlebellingham when a constable, David McGee, was shot and killed by the rebels and a Lieutenant, Robert Dunville, was wounded.

After making his way back to Dublin, MacEntee eventually joined the GPO garrison and was there through its bombardment and evacuation. After the surrender, he was one of four court-martialed on charges of murder and attempted murder at Castlebellingham. Strongly denying these charges, he said in his defence that "he lamented his [Constable McGee's] death; the constable was his fellow countryman, discharging his duty."

MacEntee was sentenced to death, but this was commuted to penal servitude for life. Released in a general amnesty in June 1917, he later became a senior Irish politician, holding many ministerial positions and finally that of Tánaiste of the Republic of Ireland from 1959-65 (deputy Prime Minister).

Early life

Seán MacEntee was born in Belfast in 1889. His father James, a Parnellite, was a successful publican and Belfast merchant, also serving as a Catholic Nationalist member of Belfast Corporation for many years.

MacEntee was educated at St Mary’s CBS and St Malachy’s College, and then qualified as an electrical engineer at the Belfast Municipal College of Technology.

He joined the Gaelic League and the Ulster Literary Theatre, but did not become a member of the IRB or Na Fianna. While his father became a close friend of Joe Devlin of the Irish Party, MacEntee did not join the official Irish Party organisation.

Radical journals

Though a reader of radical journals like The Irish Peasant and Irish Freedom, MacEntee kept outside the small group of Belfast separatists like Denis McCullough and Bulmer Hobson.

Instead he found himself as a younger man sympathetic to James Connolly's Socialist Party of Ireland, saying: "Connolly ... gathered about thirty or forty of us, of whom the majority were not Catholics, around him ... at most of our meetings, Connolly spoke ... His social theories had Irish roots ... believing that national freedom and economic freedom were complementary conditions ... Connolly's oratory, however, and all our enthusiasm availed little, and the Socialist Party of Ireland made poor headway."

Dundalk Volunteer

Initially working as an apprentice at Belfast's electrical works, MacEntee then moved towards the beginning of 1914 to Dundalk, County Louth: "I came from Belfast to take up an appointment in the Dundalk Electricity Works as assistant to the town’s electrical engineer."

Probably around Easter of that year he says he became involved in the establishment of a local corps of the Irish Volunteers in Dundalk, when there was "a meeting held at the Town Hall to organise a company of the Irish Volunteers. I was a member of the original committee."

Numbers grew, he says and "about May we could have mustered some five or six hundred earnest men, and by August at least a thousand."

World War One

World War One brought a split in the Irish Volunteer movement however. After John Redmond's urgings that the Volunteers should present themselves to fight in World War One, MacEntee says "the force began to fall apart". In Dundalk, "after the outbreak of the war and Redmond's recruiting speech, the whole thing broke up because Dundalk became a great recruiting town."

"The group of 1000 of whom we had been so proud melted away, and with this, for the time being, my enthusiasm for volunteering."

Nonetheless, a small number remained: MacEntee says those who continued in the movement believed "that in England's defeat lay Ireland's only hope for freedom..."

Rising preparations

After debating on going abroad to take up work, MacEntee was persuaded "back to rejoin the Irish Volunteers ... I withdrew my application for the post I had in mind and threw in my lot ... with the Irish Volunteers ..."

Their Dundalk Volunteer Corps, he says, "endeavoured to build up some sort of armament for ourselves." But "everything had to be done by stealth; every word about what was being done had to be spoken in a whisper."

Drilling, making buckshot, and trying "to build up an esprit de corps", lectures were arranged, including one from Seán MacDermott on 16 March 1916, "which in cold intensity of purpose was like a surgeon’s knife ... holding his audience by his personal magnetism ... [he] warned us against letting our opportunity slip away. German armies had shown themselves to be invincible; England and France were being bled to death; Ireland's long-awaited hour was at hand."

Some weeks after, "we arranged another lecture in the Town Hall on Easter Sunday and the lecturer was to be Patrick Pearse himself ... However, Pearse's Dundalk meeting did not come off; nor did he ever intend that it should. It was a ruse, a stratagem to deceive Dublin Castle ... at 7 o'clock in the very heart of Dublin he [Pearse] expected to be proclaiming the advent of the Irish republic ..."

Easter week 1916

Easter weekend

The Thursday before Easter Week, MacEntee got word that the Rising was to happen on Sunday, after which amongst his group of Volunteers "exhilaration and excitement pervaded."

Going "to Belfast to bid goodbye to my family", MacEntee returned to Dundalk, and on Easter Sunday the company made ready, with the main body beginning a march towards the village of Slane. There they were "to occupy the village, seize the bridge there across the Boyne ... and then destroy it."

MacEntee remained, one of a party detailed to seize rifles in Dundalk. They were awaiting the opportunity to do so when the countermand order arrived from Eoin MacNeill, cancelling the orders for Easter Sunday.

To MacEntee it seemed "everything had gone like clockwork, and then, suddenly, the clock stopped." He got word to the Volunteers, and reached them himself just outside Slane, where they stayed overnight: "we knew not what to do, nor where to march."

Despite this, MacEntee says in these moments "one felt a free man ... no more taking cognisance of English authority ... we were soldiers of the free Irish nation."

However, believing "our hands were tied by that confounded order", MacEntee volunteered to "proceed to Dublin to secure definite instructions", with the men meanwhile to "march slowly back towards Dundalk."

Easter Monday - 24 April 1916

On Easter Monday MacEntee managed to reach Dublin in the early hours and went to Liberty Hall, being recognised by James Connolly, and finding "much talk and much gaiety." There he met Pearse, of whom he says: "Never before was I so impressed by the bigness of any man ... I could clearly see how his personality dominated all the others there."

Pearse ordered MacEntee to return to the Louth Volunteers and gave them their orders: "We strike at noon."

Given a revolver by Pearse, MacEntee set off but missed the train. Seizing a car from its owner, he reached the Louth Volunteers and relayed Pearse's message. Seeing an opportunity to "get quick and easy transport for our men to Tara", the Volunteers took possession of cars from those returning from Fairyhouse races.

This, he says, "was not done without some excitement and a great deal of confusion", including the wounding of a farmer, Patrick McCormick, by MacEntee in the arm, for which he says "I was myself to blame." He says "my negligence, in failing to ascertain whether the catch was at the firing position or not, and, perhaps, the hastiness with which I presented the weapon were certainly blameworthy."

In a convoy, the men "set off for Tara." Stopping at the village of Castlebellingham to procure supplies, the village police officers and others were placed "under arrest and searched"; then, controversially, as the Volunteers were about to leave, two of their prisoners were shot: "To ensure, as far as possible, that no mishap would occur, I now took charge of the prisoners myself and ordered the men previously on guard back to their cars. Keeping the prisoners covered the while, I then backed towards my own car ... I had just turned to enter it, had mounted the foot-board, and was stepping inside the car, when a shot rang out. I jumped out at once and looked towards the prisoners. The lieutenant was standing quite steady and upright, two policemen were running across the road, while of the other policeman and of the chauffeur there was no sign. I thought that, like the others, they too had run away."

MacEntee says the cars stopped at the sound of the shot, and that he "ran to the leading car" and explained "that some person had fired on the prisoners." Questioned as to whether any had been hit , he says "I replied, 'I think not'" and the signal was given to start.

"The cars were moving off as I walked back, and mine was just starting as I reached it. I got into it, as it moved, and turned then to look back at the officer. He had been standing very bravely and steadily up to this but, as I looked at him now, I saw him tremble and sway and sink to the ground. I realised then, for the first time, that he had been wounded ... But already most of our cars had left ... I could not stop them, nor turn back ... every moment we thought, was precious to us … there was a doctor in the village who would be of much greater service to him than we could be, and to whom we could offer no help. I followed the other cars."

MacEntee says it "was not until nearly five weeks later, when I was brought back from Stafford to stand my court martial in Dublin, that I learned that the same shot that wounded the lieutenant [Robert Dunville] killed Constable Magee as well."

His convoy set out to get to Tara; MacEntee’s car, with its Belfast chauffeur, became diverted with others however, and they had to go into camp for the night.

Tuesday - 25 April 1916

Heading for Tara in the very early hours of Tuesday, MacEntee found "the place was deserted ... Royal Meath had not risen ..."

Hoping this meant the Volunteers had pushed on ahead, MacEntee and others continued, but his car's petrol ran out. He proceeded on foot, initially with others but eventually by himself, and with difficulty tried to get to Dublin.

Meeting a farmer and friend of Eoin MacNeill's who offered to go to Dublin by car to get information from him, MacEntee then found out "that martial law had been proclaimed, that Dublin was completely surrounded, that no German landings had taken place ... and that the bombardment of the Post Office would begin on the morrow."

It was by then "impossible for me to make Dublin before dusk", and MacEntee spent Tuesday night in a hay shed.

Wednesday - 26 April 1916

In the very early morning, MacEntee carried on walking, "now very foot-sore and compelled to halt very frequently." Drawing closer to the city, he heard "the thunder of the big guns against Dublin town." Coming against him, his road was he says "all packed with refugees, or their belongings ... hastening outwards to the country ..."

MacEntee finally arrived in Dublin, and had his first sight of the battle flag of the Republic on the GPO. "High up on its roof floated two flags: the further one, a green flag with white letters, the flag of the Workers' Republic; the other, a tricolour of green, white and orange, fronting the bullets that swept around it from Findlater's Church."

Seeing a company of Volunteers, he discovered they "intended to dash across O'Connell Street, under fire, to the Post Office ... I fell in with them."

The group managed to reach a building in Earl Street, in which there were Volunteers, and once inside MacEntee was brought "to report to Brennan Whitmore, who was in command of this section." He gets them food and sets them to duties: "Some of us were set to loop-hole walls, some to break down stairs, so as to isolate each floor from the others except at one particular place ... The main fight was being carried on between our men on the Post Office roof and the English troops at Findlater's Church and Amiens Street, so that, on this day, we saw very little of the battle."

Thursday - 27 April 1916

A quiet morning turned rapidly hectic: "As the afternoon wore on, matters became livelier. The machine guns kept up a continuous crackle, and O'Connell Street and Earl Street were swept by a continuous heavy fire, the bullets flying past and pattering on the pavement and upon the walls like hail-stones."

On duty at a window, MacEntee later sees Dublin aflame: "the whole street was filled with the lurid splendour of the flames ..." He found himself "fascinated by its awfulness."

About 9pm, they are evacuated: "The whole block of buildings, including the Imperial Hotel, which was next to us, was now well alight, and there was nothing else for us to do ... We mustered, all told, I think, about eighty souls, and marched out in single file into Earl Street."

Intending to make for the country, they come under intense fire, and eventually decide they have to "try to make the Post Office." But this proves difficult: "When I reached Henry Street, the enemy's fire was increasing in volume, rising to a 'crescendo' of intensity, until the bullets whistled through O'Connell Street like the blast of a hurricane."

Finally they make it through a window, "and, a minute later, we stood inside the Post Office."

Friday - 28 April 1916

Inside the GPO next morning, MacEntee describes what he found. The large hall "now had other uses. The greater portion of it had been screened off to form a hospital. A kit-store had been opened in another portion ... the sorting tables were in general use as sleeping bunks for the Volunteers. In a secluded corner, a priest sat hearing confessions ... Every window was manned by a rifle-man ..."

He saw "a man lying on a bed borne by four or five men, with a nurse and a couple of officers ... It was Commandant-General Connolly making his rounds. Twice wounded seriously on the previous day, he still insisted on taking as active a part as possible in the fight."

He heard James Connolly's Order of the Day being read: "This is the fifth day of the establishment of the Irish Republic, and the flag of the country still floats from the most important buildings in Dublin ... We are hemmed in; because the enemy feels that in this building is to be found the heart and inspiration of our great movement."

Pearse addressed them, and there is a moment, as MacEntee describes, of ominous calm: "We knew now the reason for the comparative inaction and quietness of the English guns. We were in the midst of comparative calm, a dead, brooding, ominous calm: soon the storm would break upon us."

Afterwards, hearing some commotion, an orderly reported "that the English had set the roof on fire." MacEntee noted: "The final attack on the Post Office had begun."

Working with Seán MacDermott to clear combustible material, MacEntee was then given a shotgun and posted with others at a window: "I could see the advance of the flames. I was fascinated by the long snakes of fire ... the fire grew fiercer and spread until it seemed as though we stood underneath a lake of flame."

After they had next cleared the ammunition store, Patrick Pearse gave them instructions: "... he spoke a few words to us, saying it had been decided to evacuate the Post Office and that we, under the command of the O'Rahilly, were to act as an advance guard ... It was about seven o'clock when we left the Post Office and filed out into Henry Street, The O'Rahilly at our head. Without commotion and without incident, we lined up and halted for a moment in the street outside."

Headed for Williams and Woods, at Moore Street, Seán MacEntee describes how "from down the street and from the houses on each side, at almost point blank range, came a burst of heavy fire." After another attempt to make their target, they came under even more concentrated fire. By now five of the group were wounded, one slightly, four more seriously. With nightfall coming, they took shelter in a stable, taking turns to rest, and treated the wounded.

Saturday - 29 April 1916

On Saturday morning, "we started boring through the party walls of the houses ... so as to strike Moore Street in the one and to work up to Williams and Woods in the other ... the sniping, which had continued most of the night, had ceased altogether."

MacEntee says he saw Willie Pearse and Captain Breen, who was carrying a white flag. Pearse told him that the Volunteers had surrendered: "'What!', I cried, speaking to Pearse and breaking down with emotion, 'Has it come to this?' 'It has', Pearse replied ..."

He says they marched to O'Connell Street, en route seeing the O'Rahilly's body "lying on the pavement, his uniform riddled." Other prisoners arrived, until by the evening he estimated they numbered in the hundreds. They were then marched to the Rotunda, and "there, in the open, in a space where there was scarcely room for us to stand, we were compelled to spend the night in bitter cold ... of that night, I will not speak ..."

Sunday - 30 April 1916

Next morning, MacEntee was taken with the others from the Rotunda: "We were marched through the streets to Richmond Barracks ... The city was quiet and almost deserted as we trudged along. Here and there, at some few windows, were a few onlookers, most of them, so far as one could judge, sympathetic."

There they were searched, and 'G' division policemen moved through the group, according to MacEntee, selecting some of the men including Willie Pearse, Seán MacDermott and Joseph Plunkett. MacEntee himself was kept in the main block, and the order was given for them to leave the Barracks.

Outside the gate as the prisoners left, "a mob was gathered, composed almost entirely of women, soldiers' wives and dependents. They hooted and jeered and cursed us with an insensate rage, trying to strike at us through the files of the guards in their fury ... we passed through them, however, turned by Kilmainham Jail and entered the grounds of the Royal Hospital."

They got to the Quays, and boarded "an old tub, a cattle-boat ... Prisoners, we left Ireland; and thus ended our Easter Week."

MacEntee's memoirs end here.

After the Rising

General court-martial

On 1 May 1916, MacEntee was moved to Stafford prison, but was back at Richmond Barracks for his general court martial on 9-10 June 1916, where he was represented by Henry Hanna, KC. Along with three others, the charges included the murder of Constable Charles McGee at Castlebellingham, and the attempted murder of Lieutenant Robert Dunville.

Reported The Irish Times: MacEntee "positively denied the charge of murder ... the constable received no abuse from him, and he lamented his death." MacEntee also refuted a charge "of having given assistance to the King's enemies", his defence noting that he had previously applied to the 16th Division for a Commission, the application having fallen through. He pleaded guilty to having taken part in the rebellion.

MacEntee was sentenced to death, this being commuted to penal servitude for life.

Later life

Seán MacEntee was imprisoned at Dartmoor, Lewes and Portland prisons, being released in the general amnesty of 1917. Serving on the Executives of both Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers in 1917, he went on to be elected as a Sinn Féin MP for Monaghan South in 1918. He took his seat in Dáil Éireann in January 1919, after its establishment.

During the War of Independence, MacEntee was Vice-Commandant of the Belfast Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). He opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, being strongly against partition, and during the Irish Civil War he was interned by the Irish Free State government at Kilmainham and Gormanstown prisons (1922-3).

He would go on to become a founder of Fianna Fáil, and to be elected as a TD for county Dublin in 1927. He subsequently had a long political career, during which he held a range of government ministries, becoming Minister for Finance, 1932-9; for Industry and Commerce, 1939-41; Minister for Local Government and Public Health, 1941-8; Minister for Finance, 1951-4; Minister for Health, 1957-65, and Minister for Social Welfare, 1957-61; and Tánaiste, 1959-65.

Seán MacEntee retired from politics in 1969, and died in 1984.

These pages are based on personal testimonies and contemporaneous accounts. They reflect how people saw things at that time and are not meant to be a definitive history of the period.

The words of Seán MacEntee

Voices 16 objects

Voices 16 galleries

Credits

Seán MacEntee's recollections are taken from his Witness Statement and his memoir - Episode At Easter (published by M.H. Gill & Co.). Extracts are published with the kind permission of Seán MacEntee's family, Gill & Co. and the .

Further biographical information from Dr Tom Feeney's biography has been included with the kind permission of the publisher, the . Additional information courtesy of .

Seán MacEntee's image is reproduced with the kind permission of his family.