'I've been naughty for years': Maurice Girodias and the 'dirty books' that helped to modernise literature

27 October 2016

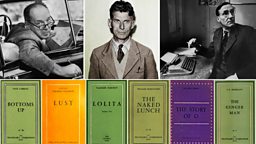

Olympia Press is known for publishing some of the most significant authors of the post-war era such as Vladimir Nabokov, J.P. Donleavy and William Burroughs. BRIAN MORTON discovers how Maurice Girodias sought to destroy censorship with a series of erotic green paperback books.

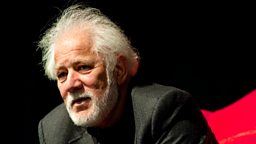

Though Maurice Girodias had a problem with the definite article – adding spurious ones to two of his most notorious titles, Story of O and Naked Lunch – he remains the representative book publisher of the 20th Century, or perhaps more accurately, the first truly postmodern publisher.

It's a profession that almost inevitably throws up mixed reputations. Girodias has been seen as everything from saintly to demonic, intensely loyal and treacherous, generous and grasping, as the champion of brave modernity in literature and as a shabby purveyor of “dirty books”.

Girodias has been seen as everything from saintly to demonic...as the champion of brave modernity in literature and as a shabby purveyor of “dirty books”.

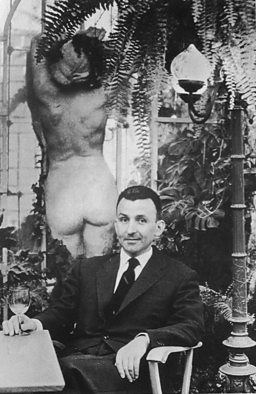

The most famous photographs find him respectively in the garden of the Grande Séverine in Paris, with an empty glass on the table behind him and a sculpted female rear on a level with his head, and late in life, wearing a similar unreadable grin, but with a human skeleton leering over his shoulder.

Every man is a “man of contradictions”, and no two images sum anyone up, but these ones come close.

Girodias's difficulties with the definite article may be an expression of his unusual transcultural background. He was the son of Jack Kahane, the Manchester-born publisher of “difficult” authors like James Joyce, Radclyffe Hall, Frank Harris and Henry Miller, a devoted “booklegger” whose business practice at Obelisk Press, swiftly passed on to his son at the even more notorious Olympia Press, and was “to begin a publishing business with or without capital and then run its nose into the ground with all possible speed”.

Authors like to be lionised. They also like to be paid. Throughout his career, Girodias and his above-counter authors were locked in seemingly irreconcilable differences over copyright and royalties.

They included J. P. Donleavy whose The Ginger Man (this one does have a “the” in the right place) became the focus of a never-ending feud; even in the mid-90s, five years after Maurice's death, Donleavy was still referring to his erstwhile publisher as “Girodi-ass” but with a certain affection in his voice.

His objection, apart from the ones the lawyers were asked to pick apart, was that a work of literature, albeit bawdy and picaresque, had been published in a list known innocuously as the Traveller's Companion but including titles like Frances Lengel's White Thighs, Angela Pearson's The Whipping Club, Marcus Van Heller's historical The Loins of Amon and Count Palmiro Vicarion's Lust.

Girodias on the freedom to publish

Maurice Girodias: "I have been naughty for a few years"

The French publisher on how his 'dirty books' helped to destroy censorship.

These were the “dirty books” (or “DBs”) that helped launch Olympia in post-war Paris. Girodias, a part-Jew with an English background, had managed to avoid trouble with the Nazis, leading to predictable charges of collaboration, though in his case it may simply have been wily charm.

He came out of the war with a supply of printing paper and a cellar full of canned celery. The former proved more profitable.

The authors of the “dirty books” liked to be paid for their work as well, though mostly cash in hand, and with little quibble about long-term copyright.

He came out of the war with a supply of printing paper and a cellarful of canned celery. The former proved more profitable.

All but Pearson of the group above is a pseudonym: “Lengel” was the Scot Alexander Trocchi, “Van Heller” was John Stevenson, the spurious “Count” was actually Christopher Logue; mostly emigrés, mostly broke, collectively sex-obsessed and cheerfully transgressive. Another of the group was the splendidly named “Akbar del Piombo” (né Norman Rubington) whose Fuzz Against Junk is a counterculture classic.

It was in this environment that not only Donleavy, but also Samuel Beckett and Vladimir Nabokov found themselves. Not always comfortably. If the common subject matter was sex (or in Beckett's case, death, the other presence in those Girodias portraits) there was a certain assumption on the part of Nabokov and the more litigious Donleavy that while the “DBs” were merely that, their books were art. Posterity would agree, but the genius of Olympia was its blurring of category.

If The Ginger Man and Lolita were two of the list's defining titles, two more pointed more sturdily at its ambiguity. Mason Hoffenberg, a chaotic drug user with a gift of salacious rhetoric, had written for Girodias as “Hamilton Drake” (Sin For Breakfast, anyone?) and as “Faustino Perez” (Until She Screams, why don't you?), but he also most famously collaborated with fellow-American Terry Southern on the lubricious modern fable that is Candy, an episodic narrative of desire whose reflexivity mostly frustrated the mackintosh brigade who wanted efficient one-handed porn but delighted the intelligentsia.

Another furious round of litigation ensued, from which Candy doesn't so much stand remote as a modern classic as embrace by way of sequel.

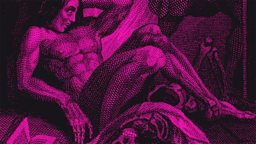

The final and arguably most representative Olympia title of all is another glimpse of female (or is it really male?) sexuality, the eternally strange and troubling Story of O by “Pauline Réage”.

Dogged detective work by Girodias/Olympia biographer John De St Jorre eventually proved that “Réage” was actually editor and translator Dominique Aury and that the novel, with all its baroque sado-masochistic apparatus, multiple penetrations and its little remarked sapphic aspect, had been written as a love-letter to an older man, Jean Paulhan.

It was he who arranged publication and he who made sure that the book was introduced into the highest echelons of French literary culture, where (in its problematic way) it remains.

A later work by “Réage” contains lines that go some way towards summing up the mystique, the fascination and the lasting cultural or philosophical importance of what Maurice Girodias did at Olympia.

He collapsed the distinction between “high” and “low” culture; he revealed that the “sacred” bond between author and publisher is always a devil's pact; and he suggested with a smile that “dirty books” and their cloaked authors offered a deep but usually unspoken truth about literary culture.

Here is “Réage” from the disarmingly innocent-sounding A Girl In Love:

“Who am I finally...if not the long silent part of someone, the secret and nocturnal part which has never betrayed itself in public by any thought, word, or deed, but communicates through subterranean depths of the imaginary with dreams as old as the world itself...”

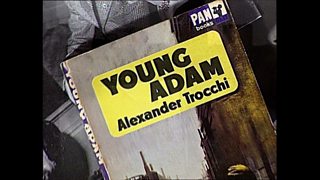

How Young Adam was 'sexed up'

Alexander Trocchi produced a series of erotic titles for Maurice Girodios' Olympia Press including Young Adam, which produced a successful film adaptation in 2003.

Biographer James Campbell reveals that, in order to arrange the publication, Girodios famously requested Trocchi altered the book to feature a sex scene in every sixth page.

Family ties: Jack Kahane

-

![]()

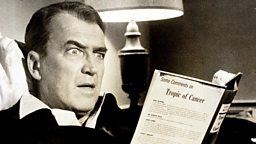

Read the feature on Jack Kahane, Girodias' father, who published Lady Chatterley's Lover and Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer in the 1930s.

Girodias was the son of Jack Kahane, the Manchester-born publisher who took advantage of a legal loophole in France's obscenity laws that meant books published in English were not subject to censorship.

His Obelisk Press would publish some of the great literary classics of the 20th century including DH Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover and books by James Joyce, Radclyffe Hall, Frank Harris and Henry Miller.

A Very British Pornographer

In a new documentary on Kahane for �鶹�� Four, Neil Pearson travels to Paris to follow the trail of one of the most important - and least likely - figures in 20th century literature.

More from Books

-

![]()

Seven must-read novels by female authors.

-

![]()

Tolkien's own illustrations of his fantasy universe.

-

![]()

The author picks his three favourite works of science fiction.

-

![]()

Judge these books, and their genres, by their covers.