The 17th-Century sci-fi trailblazer you’ve never heard of

18 June 2018

Mary Shelley is credited by some . But long before Frankenstein there was a groundbreaking work of prose written by Margaret Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. As her work is honoured as part of the , BRIAN MORTON delves into The Blazing World.

In October 2002, a man called Dallas Thompson appeared on the cult radio show and described how he had travelled into the planet’s interior through an opening at the North Pole.

Thompson was lying in the remains of his crashed car when all this happened, but before the California fire service had got to him, he’d seen sabre-tooth tigers, hairy mammoths and had met representatives from the Lost Tribes of Israel.

Thompson, who has since gone to ground (in the other sense), wasn’t the first, and won’t be the last to claim some experience of the Hollow Earth. Adolf Hitler was a believer, and there are those who believe he lives there still, planning a comeback.

Edgar Allan Poe made reference to the theory at the climax of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym. So, too, did Edgar Rice Burroughs. Most famously Jules Verne , rather than at the Pole, in Journey to the Centre of the Earth.

All these men were late adopters, though.

The most vivid description of the kingdom of inner space, its life, its fauna, society and culture, was published in 1666, by Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle.

That she was writing at all was the wonder

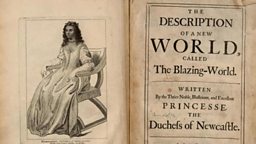

Cavendish's extraordinary fable is known in full as .

It is the story of a beautiful woman who is kidnapped by a suitor but who is then caught up in ocean storms that drive their craft northward into realms of ice.

The crew dies of cold but the woman, warmed by both beauty and intelligence, slips through what Jason H. Pearl describes as an "interstitial passageway [which] exists as a wrinkle in space", and finds herself in a world peopled by Bear-men, Fox-men, Bird-men and other creatures.

Once the Emperor of the Blazing-World establishes that she is not a goddess, he marries her and makes her his consort.

In his realm, skin colour does not seem to matter, though it is much more various than in our own; positively Farrow & Ball, in fact. Likewise, social roles are distributed without conflict or friction.

One doesn't have to be very sharp-eyed to note that Cavendish was writing just a few years after the Restoration and in full memory of the Civil War; she was 26 when .

That she was writing at all was the wonder.

As we celebrate the achievements of extraordinary women, and the intellectual and cultural achievements of the North, it's worth pausing to consider how unlikely Margaret's actually were.

The title of Pearl's book, , is an indication of how she is generally positioned: as a forerunner of modern science fiction and utopian fantasy.

Women, even of her class, were not expected to dabble with chemicals and lenses

The Blazing World is an acknowledged influence on Alan Moore, who includes references to it in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

Again, you don’t have to be a quick-eyed feminist to note the gender issue there, and this goes to the heart of Cavendish's own story and that of her remarkable fantasy fiction.

The Blazing World was actually published as an appendix to another work, which bears an even more unlikely title to appear above a female name in the 17th century.

Her were the result of her own scientific endeavour.

Women, even of her class, were not expected to dabble with chemicals and lenses, but Cavendish had an extraordinarily speculative mind: The Blazing World even includes her intuition that light exists as both wave and particle, this nearly three centuries before that became orthodoxy.

One wonders whether The Blazing World, issued with a faintly patronising poem of approval by her husband William Newcastle, were issued as a kind of camouflage, as if to disguise (in her own words) the Philosophical within the Romancical and "meer Fancy".

In "My Birth, Breeding, and Life", Margaret is ever anxious to point out how retiring and painfully shy she is, though "I hold it necessary sometimes to appear abroad" (all in the line of wifely duty, is the implication).

William compares her (favourably?) with Columbus, who found what was already there: "But your Creating Fancy, thought it fit / To make your World of Nothing, but pure Wit".

Was this to disguise or soften the subversive nature of what Margaret was doing?

A later Margaret always liked to insist that she was not just the first female prime minister but the first scientist to occupy Number 10.

A later Margaret always liked to insist that she was not just the first female prime minister. There's still resistance to both.

Margaret Cavendish was all too aware, or was made aware that she was speaking outside her station, even as a great lady.

Her political commentary in The Blazing World is decidedly egalitarian, albeit under a monarchy with social duties strictly demarcated.

Her ambition to be "Margaret the First" is easily dismissable as a solitary lady’s imaginary whim. And yet, what is rarely noticed is that Margaret appears as a character in her own fantasy.

The Empress may well be a self-projection, but when that great lady is looking for intellectual models and leafing through "Galileo, Gassendus, Des Cartes, Helmont, Hobbes, H. More, &c", another name is proposed: "the Duchess of Newcastle; which although she is not one of the most learned, eloquent, wittyand ingenious, yet she is a plain and rational Writer: for the principle of her Writings, is Sense and Reason".

Perhaps, in writing fantastically, Margaret Cavendish, woman of her time, and yet not, just wanted to be taken as seriously as the men.

is part of at the Great North Museum.

The , which runs from 22 June to 9 September 2018, celebrates the North of England’s pioneering spirit with a programme of exhibits, live performances and new artworks.

Three venues - BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Sage Gateshead and Great North Museum - act as hubs for the exhibition and there are trails themed by art, design and innovation exploring Newcastle and Gateshead.

Great Exhibition of the North

-

![]()

Opening ceremony

Â鶹Éç Arts and Â鶹Éç North East present live coverage on Friday 22 June.

-

![]()

The Women by Women exhibition showcases women on both sides of the lens.

More on Margaret Cavendish from Â鶹Éç Radio

-

![]()

The Duchess Who Gatecrashed Science

Naomi Alderman asks why Margaret Cavendish fascinated and infuriated the men of her era.

-

![]()

Free Thinking

Why are women, like Margaret Cavendish, left out of some historical accounts?

-

![]()

Woman's Hour

Includes an interview with Danielle Dutton who wrote a novel, Margaret the First, about Margaret Cavendish.

-

![]()

In Our Time

The Cavendish family produced a whole succession of figures who pushed science forwards.

More from Â鶹Éç Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms