The real deal: How William McIlvanney transformed Scottish fiction

8 December 2015

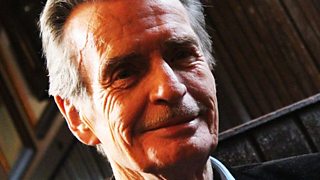

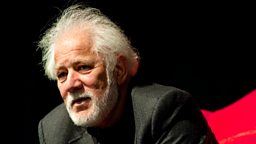

William McIlvanney, one of Scotland's greatest writers whose novel Laidlaw was hailed for changing the face of crime fiction, . A documentary, , premiered at the Glasgow Film Festival in February 2015 and aired later on Â鶹Éç Two Scotland. Here, Â鶹Éç Arts presents Brian Morton's profile of the author, written to coincide with the documentary's premiere, and also a set of exclusive conversations and readings not seen in the film.

From a cabbage patch to a harvest of bloody needles in just three literary generations. If there is a direct line from the so-called 'Kailyard' writers of the late 19th century, many of whom were Presbyterian ministers, to the playful savagery of Irvine Welsh and the still rising body-count of 'tartan noir', then at its midpoint stands William McIlvanney.

He is the acknowledged father of contemporary Scottish crime fiction, but also the thoughtful chronicler of a particular way of life and of thinking, whose uniqueness to Scotland was again evident in the referendum debate.

The acknowledged father of contemporary Scottish crime fiction is also the thoughtful chronicler of a particular way of life

The revolt against the Kailyard was led by writers like George Douglas Brown, whose The House With The Green Shutters (1901) smashes the complacency of small-town life, and J. MacDougall Hay, whose Gillespie (1914) exposes an older Scottish way of life to the brutal irruption of modernity.

Brown in particular influenced the writers of the Scottish Renaissance, who wanted to rid their literature of smallness and parochialism.

They in turn opened the way for the documentary 'realism' (which was still three-parts fancy) of H. Kingsley Long's and Alexander McArthur's No Mean City (1935) and then for a tide of new Scottish fiction in the 1960s and 1970s which looked hard at a country which had lost an imperial role and not yet found a convincing new voice.

The fiction of Robin Jenkins (1912-2005) was often set in exotic, British Council-invested places, but it was always about Scotland. Archie Hind's The Dear Green Place (1966) found a new kind of poetry in Glasgow, the Gles-Chu of the title.

Alan Sharp turned a Joycean eye on the Clyde littoral in A Green Tree In Gedde (1965) and The Wind Shifts (1967); the trilogy remained unfinished when Sharp went off to Hollywood. Meanwhile Gordon Williams found a new, unflattering but still hopeful angle on Walter Scott's country and Robert Burns's country in From Scenes Like These (1968).

Burns's country is also William McIlvanney's country. He was born in Kilmarnock in 1936, a defining year of the Depression and of the slide towards another European war.

His father was a former miner, but father and mother both had the typical autodidactic urge of the Scottish working class of that period and William and his brother Hugh, now a distinguished sports writer, both grew up with a knowledge of and love for books.

William studied English literature (and that would have been the course title in those days) at the University of Glasgow, the first in his family to receive higher education, thereafter training and working as a teacher in his native quarter.

The same observational sharpness that fuels the fiction also yielded almost forensically accurate verse

McIlvanney’s first novel was a thinly disguised reworking of the Hamlet plot, called Remedy Is None (1966). It was followed two years later by A Gift From Nessus, a typical second novel in its even more studious literariness.

And then for a moment it seemed that McIlvanney’s natural bent might be poetry. Like John Updike, the same observational sharpness that fuels the fiction also yielded almost forensically accurate verse, and The Longships In Harbour (1970) is a substantially undervalued example of modern Scottish poetry.

But then came a double breakthrough, first with Docherty (1975), a book which so precisely established its central character that old miners constantly approached McIlvanney to say that their story had at last been told.

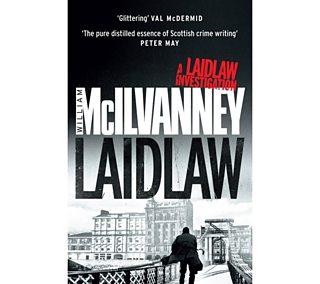

Two years on from that, a surprise. In Laidlaw (1977) McIlvanney seemed to make a turn into genre, with the first of what would become three books about the Glasgow detective Jack Laidlaw, a man who kept editions of Unamuno and Kierkegaard in his desk drawer, along with a half of whisky and a pair of cuffs.

A cluster of highly recognisable secondary characters helped Laidlaw with his existential enquiries and a brand of writing about crime and the pursuit of crime was born, in which big ideas sat alongside procedural niceties.

It is hard to imagine the work of Val McDermid or Ian Rankin, who acknowledges the debt, without Laidlaw or the subsequent books The Papers Of Tony Veitch (1983) and Strange Loyalties (1991).

And it is hard now to picture a certain aspect of Scottish life without seeing it through McIlvanney’s eyes.

So confidently does he present his characters in a naturalistic but not self-consciously researched environment that when Docherty’s grandson turns up in The Kiln (1996), the finest of his more recent novels, we accept his presence as readily as we do a third-generation character in William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha sequence and ask the same question: whether the author possesses his material, or whether it possesses and expresses him.

The essence of McIlvanney’s vision, and his ability to live with words as well as by words, is that he is equally skilled as a poet and, like his brother, as a journalist. The two were mixed in Weddings And After (1984) and other bulletins have come along, not least in his regular blog.

And yet there is no didactic strain in any of this. McIlvanney gave up teaching in 1975, when Docherty became real, and has ever since shown no desire to deliver lectures, flag up symbolism, or point us to big conclusions.

Like his distant ancestor James Galt, who set out early 19th century Ayrshire life with pawky realism, McIlvanney looks and reports and finds an unsuspected music in everyday lives and extraordinary events.

The of this article was published in February 2015, to accompany the film.

William McIlvanney tributes

-

![]()

Janice Forsyth and Christopher Brookmyre discuss McIlvanney's influence, with an archive interview with the late Scottish writer.

-

![]()

Â鶹Éç News reports on William McIlvanney's death, with tributes from the Scottish literary world.

Watch the programme

-

![]()

On Â鶹Éç Two Scotland on Tuesday 15 December at 10pm, and on Â鶹Éç iPlayer for 30 days thereafter.

Exclusive readings

Programme clips

Related Links

-

![]()

Discover the best of books and authors from Â鶹Éç Arts

More from Books

-

![]()

Seven must-read novels by female authors.

-

![]()

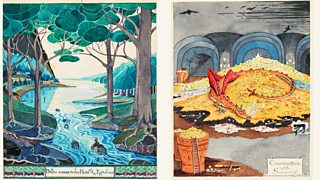

Tolkien's own illustrations of his fantasy universe.

-

![]()

The author picks his three favourite works of science fiction.

-

![]()

Judge these books, and their genres, by their covers.