Episode Transcript – Episode 12 - Standard of Ur

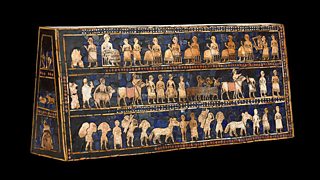

Standard of Ur (made around 4,500 years ago). Wooden box inlaid with mosaic, found in southern Iraq

At the centre of pretty well all great cities, in the middle of the abundance and the wealth, the power, and the busy-ness, you'll find a monument to Death on a massive scale. It's the same in Paris, Washington, Berlin and London.

At the moment, I'm standing in Whitehall, just a few yards from Downing Street, the Treasury and the Ministry of Defence, where the Cenotaph marks the death of millions in the great wars of the last century. Why is death at the heart of our cities? Perhaps one explanation is that in order to retain the wealth and power that our cities represent, we have to be willing to defend them from those who covet them. In this week's programmes, I'm looking at the moment, about five thousand years ago, when people first started living in cities.

Today's object, from one of the oldest and the richest of them all - seems to say quite clearly that the power of cities to get rich is indissolubly linked to the power to wage and win wars.

"For the Iraqis, it's a symbol of their very deep long tradition, being one of the centres of civilisation." (Lamia al-Ghailani)

"Since the invention of history, five to six thousand years ago, a large part of history has been the history of competing classes and class conflicts - Marx was not so wrong." (Anthony Giddens)

Cities started around five thousand years ago, when some of the world's great river valleys saw a step change in human development. Fertile land, farmed successfully, became in just a few centuries very densely populated. On the Nile this hugely increased population led, as we saw in the last programme, to the creation of a unified Egyptian state. In Mesopotamia, the land between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates - now Iraq - the agricultural surplus, and the population that could support, led to settlements of up to 30,000 - 40,000 people, a size never seen before, and to the first cities. Co-ordinating groups of people on this scale obviously needed new systems of power and control, and the systems devised in Mesopotamia around 3000 BC have proved astonishingly resilient. They have pretty well set the urban model to this day. It's no exaggeration to say that modern cities everywhere have Mesopotamia in their DNA.

Of all these earliest Mesopotamian cities, the most famous was Ur. So it's not surprising that it was at Ur that the great archaeologist Leonard Woolley chose to carry out his excavations in the 1920s. At Ur, Woolley found royal tombs which themselves could have been the stuff of fiction. It was Woolley who famously gave Agatha Christie both a husband - she married his assistant - and the inspiration for a novel: �Murder in Mesopotamia'. There was a queen and the female attendants who died with her, dressed in gold ornaments; there were sumptuous headdresses; a lyre of gold and lapis lazuli; the world's earliest known board-game - and a mysterious object, which Woolley initially describes as a plaque:

"In the farther chamber was a most remarkable thing, a plaque, originally of wood, twenty three inches long and seven and a half inches wide, covered on both sides with a mosaic in shell, red stone, and lapis; the wood had decayed, so that we have as yet little idea of what the scene is, but there are rows of human and animal figures, and when the plaque is cleaned and restored it should prove one of the best objects found in the cemetery."

This was one of Woolley's most stupendous finds. The 'plaque' was clearly a work of high art, but its greatest importance is in what it tells us about the exercise of power in these early Mesopotamian cities.

What Woolley found is now in the British Museum - and I'm just coming in to the Mesopotamian galleries to find it - here it is: it's about the size of a small briefcase, but it tapers at the top - so that it looks almost like a large bar of Toblerone. It's decorated all over with small mosaic scenes. Woolley called it the Standard of Ur, because he thought it might have been a battle standard that you carried high on a pole in a procession or into battle. We've kept that name, but it's actually hard to see how it could have been a standard of that sort, because it's obvious that the scenes are meant to be looked at from very close up. Some scholars have thought it might be a musical instrument or perhaps just a box to keep precious things in, but we just don't know. We asked Dr Lamia al-Ghailani, a leading Iraqi archaeologist who now works in London, what she thinks this is:

"Unfortunately, we don't know what they used it for, but for myself, it represents the �whole' Sumerians. It's war, it's peace, it's colourful, it shows how far the Sumerians travelled - because the lapis lazuli came from Afghanistan, the red marble came from India, and you've got all the shells which came from the Gulf. And so it's a fantastic piece, and it's beautiful!"

So far in these programmes, each of the objects I've looked at has been made in a single material - stone or wood, bone or pottery - all of them substances that would've been found close to where its maker was living. Now, for the first time in the series, I'm looking at an object that is made of several different, quite exotic materials. Only the bitumen which held together the different pieces could have been found locally, it's a trace of what is now Mesopotamia's greatest source of wealth - oil.

What kind of society do you need to be able to gather these materials in this way? Firstly it needs to have agricultural surplus, but it then needs a structure of power and control that allows the leaders to mobilise that surplus and exchange it for exotic materials along extended trade routes. That surplus will also feed and support priests and soldiers, administrators and, critically, craftsmen able to specialise in making complex luxury objects like the Standard. And this is the society that you can see on the Standard itself.

On the Standard, the scenes are arranged like three comic strips, one on top of each other. One side shows what must be any ruler's dream of how a tax system should operate. In the lower two registers, people calmly line up to offer their tribute of produce and fish, sheep, goats and oxen; and on the top register, the king and the elite, probably priests, are feasting on the proceeds while somebody plays the lyre. And you couldn't have a clearer demonstration of how the structures of power work in Ur: the land workers shoulder their burdens and deliver offerings, while the elite drink with the king - and to emphasise the king's pre-eminence, the artist has made him much bigger than anybody else - in fact so big that his head breaks through the border of the picture. What we are looking at in the Standard of Ur is a totally new model of how a society is organised. We asked the former Director of the London School of Economics, Professor Anthony Giddens, to consider this shift in social organisation:

"From having a surplus, you get the emergence of classes, because some people can live off the labour of others, which they couldn't do in traditional small agricultural communities - everybody worked. Then you get the emergence of usually a priestly warrior class, you get the emergence of organised warfare, you get the emergence of tribute and something like a state - which is really the creation of a new form of power I think. So all those things hang together, and that was the way it happened really, the conjunction of all those things.

"You can't have a division between rich and poor when everyone produces the same goods. So it's only when you get a surplus product which some people can live off and others have to produce, that you get a class system; and that soon emerges into a system of power and domination. And you see the emergence of individuals who claim a divine right, that integrates with the emergence of a cosmology, you have the origin of civilisation there but it's bound up with blood, it's bound up with dynamics, it's bound up with personal aggrandisement - you can't really have those things in the same way in a small village community."

If one side of the Standard shows the ruler running a flourishing economy, the other side shows the army he needed to protect it - and that brings me back to the thought that I began with; that it seems to be a continuous historical truth - that once you get rich you then have to fight to hang on to it. So, it's not surprising that the king of civil society that we see on one side also has to be the commander-in-chief we see on the other. The two sides of the Standard of Ur are in fact a superb and alarmingly early illustration of the military-economic nexus, of the ugly violence, that underlies prosperity. Let's turn to the war scenes.

Once again, the king's head breaches the frame of the picture; he alone is shown wearing a full-length robe and he holds a large spear, while his men lead prisoners off either to their doom or to slavery. Victims and victors look very alike - because this is almost certainly a battle between close neighbours. The losers are shown stripped naked to emphasise the humiliation of their defeat. In the bottom row, we have some of the oldest-known representations of chariots of war, and one of the first discoveries of what was to become a classic graphic technique - the artist shows the asses that are pulling the chariots, moving from a walk to a trot to a full gallop, gathering speed as they go. It's a technique that no graphic artist would better until the arrival of film.

Woolley's discoveries at Ur coincided with the early years of the modern state of Iraq, created after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War. One of the focal points of that new state was the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, which received the lion's share of the Ur excavations. From the moment of discovery, there was a strong connection between Iraqi national identity and the antiquities of Ur, so the looting of antiquities from the Baghdad Museum during the recent war in Iraq was felt very profoundly by the Iraqis:

"The plundering of Baghdad has continued for a third day to the consternation of international aid agencies ..." (Â鶹Éç news report)

" ... at the National Museum in Baghdad we were shown where Sumarian artefacts were ripped down when it was looted just after the war, but experts say an even greater cultural crime is now being committed. This official calls it a �rape of the history of mankind'." (Â鶹Éç news report)

But for Iraqis in particular, these objects have a very special place. Here's Lamia Al-Ghailani again:

"For the Iraqis, we think of it as part of the oldest civilisation - which is in our country, and we are descendants of it. We identify quite a lot of the objects from the Sumerian period that have survived until now .... so ancient history is really the unifying piece of Iraq today."

So Mesopotamia's past is a key part of Iraq's future. Archaeology and politics are set to remain closely connected as, tragically, are cities and warfare.

I began this programme by suggesting that all urban societies might ultimately depend on violence to defend their wealth, but in the next programme, I'll be taking a more hopeful view. I'll be in the Indus Valley, in modern Pakistan and India, looking at a civilisation whose cities were defined, not by memorials, kings and victories but, apparently, by their peaceful plumbing!

-

![]()

Listen to the programme and find out more