How do we understand abstract art?

Claudia Hammond:

ãAt first glance the irregular shapes and geometric patterns of abstract art could appear difficult for the human brain to interpret. Art exhibitions like this one at the Saatchi Gallery in London, provide a visual feast for the brain, but not everybody sees it in the same way. While some will feel engaged and stimulated, others will find it impenetrable and difficult to understand. We are processing an enormous amount of information when viewing a piece of abstract art. Scientists can monitor these processes, giving them an insight into how the brain responds and this is beginning to reveal some fascinating results.ã

Art and our brains

When we visit an art gallery, traditional landscapes and portraits are easy to enjoy. We recognise the subject from our own knowledge of the world. Abstract art is more difficult. We are often unsure about what we are seeing. And uncertain of what response is expected.

Can modern science play a role in helping us understand the processes happening in our brain when we view a piece of abstract art? And can it predict whether we will like what we see?

Inside the mind of the viewer

Claudia and neuroscientist Dr Luca Ticini discuss how our brains process visual art. Our natural response to artworks can be altered by science. When magnetic pulses are applied to specific parts of the brain, our enjoyment can be raised or lowered.

Looking at beautiful artworks activates the pleasure centres of the brain. Applying small magnetic pulses that interfere with the neural activity in the prefrontal cortex decreases aesthetic appreciation for both abstract and representational art. But applying this to just the posterior parietal area decreases enjoyment of representational art only. This is because this area is more involved in the recognition of objects, showing that the brain processes representational and abstract art quite differently.

Images featured: The Hay Wain by John Constable, National Gallery; Small Horizon with Orange, Lime, Lemon and Cherry: June 1957 by Patrick Heron. ôˋ The Estate of Patrick Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2014. Bridgeman Images

How do we understand abstract art?

Claudia Hammond (CH): ãSo Luca youãve been investigating how the brain actually processes art when we look at it. How much do we know about what goes on when weãre looking at a piece of abstract art compared with something much more traditional and representative?ã

Luca Ticini (LT): ãWhen we observe a representational painting our eyes would stop on salient features like the dog, the house, the man. While when we observe an abstract painting we perceive it more uniformly so the eyes will scatter around, will scan the painting without stopping in a particular place. This is also reflected in the activity of the brain. When we observe a representational painting, there are specific areas in the brain, well localised, that are activated and are specialised for processing letãs say houses, faces and dogs etc. While when we observe abstract painting we donãt have this kind of activity. The activity in the brain is widespread and so we cannot really locate it.ã

CH: ãSo we know that some people really like abstract art and some people donãt, do we know whatãs going on in the brain if people do like it?ã

LT: ãYes, if we observe this model of the brain, so when we like a piece of art there is an increase of activation in our brain in specific areas, particularly in the orbital frontal cortex, which is located in between the eyes, in the prefrontal cortex and in the posterior parietal cortex. And we can even enhance or reduce the activity in these areas and therefore enhance or reduce the appreciation of art. For instance, if we stimulate by applying small magnetic pulses, these areas of the brain for instance the prefrontal cortex, what happens is that we will decrease the likability of the paintings whether they are abstracts or representational. Instead if we pulse the parietal cortex, we will decrease selectively the likability of paintings which are representational because this area is more involved in the recognition of objects.ã

CH: ãThat seems absolutely amazing that you can use this to actually change whether someone likes the picture theyãre standing in front of or not.ã

LT: ãYes absolutely and if you apply small currents in the prefrontal cortex you can even increase the appreciation of art.ã

CH: ãSo this is what galleries need? The need to have one of these.ã

LT: (laughs) ãAbsolutely.ã

Context is key

How our brains process visual information is not the only factor to consider.

Scientific studies indicate that we derive more or less pleasure depending on what we know about the subject. This applies to our enjoyment of, for example, food and drink as well as art.

Gallery authenticity

One study showed that people liked paintings less if they thought they were made by a computer rather than a human artist, even when the pictures were actually identical.

Parts of the brain involved with memory were stimulated more - it might be that remembering information about art and culture gives us greater pleasure.

Artists on abstract art

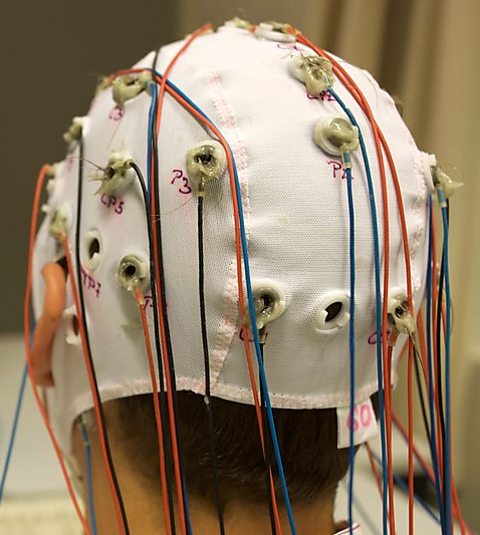

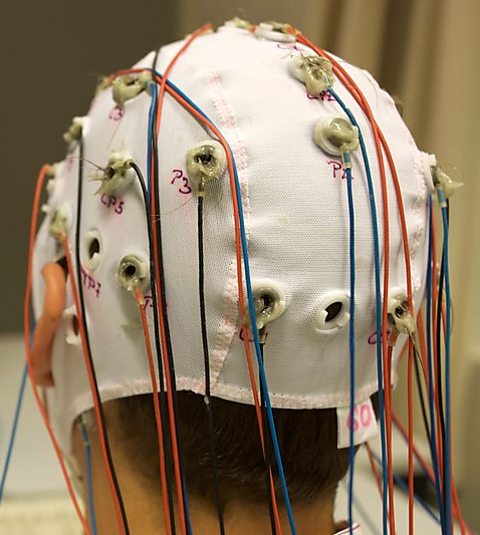

This is reinforced by research which suggests artists tend to enjoy abstract art more than non-artists. Another study has recorded the electrical rhythms occurring in the brains of both groups, by using electrodes glued to the scalp. This showed that the artistic background of the individual considerably influenced how abstract art is processed. The pattern of brain activity in artists revealed focused attention and active engagement with the visual information. This may be due to making use of memory to recall other artworks in order to make sense of the image.

The unseen hand

Scientific research suggests that the human brain unconsciously simulates the brush-strokes of an artwork due to cells known as mirror neurons.

It was known that these cells fire when carrying out and observing actions. Recent research suggests this applies not just to actions we observe, but also to actions used by the artist to create works of art.

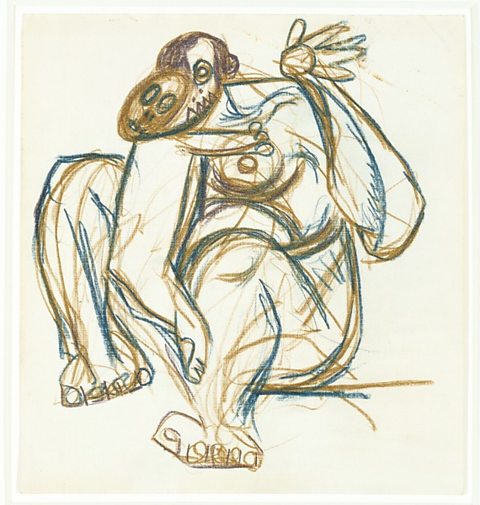

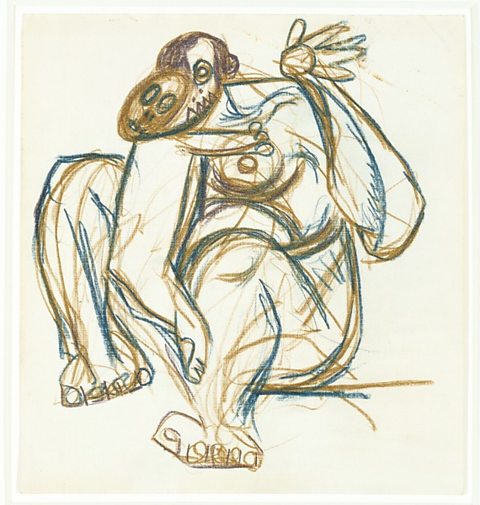

For example, when looking at the painting on the right our brain can imagine the movements performed by Kandinsky in its creation. Brush-strokes are a major feature of abstract art. Unlike figurative paintings, where there is an attempt to capture an object from the natural world, they are a means within themselves.

The artist and psychology

Kandinsky was keenly interested in psychology, a relatively new discipline when he began painting abstract art in the early 20th Century. This had a significant impact on the art he produced.

Wassily Kandinsky

Kandinsky, widely credited as the first abstract artist, called it the 'science of the soul' and his art explored the relationship between colour and form.

He carried out ãpsychological testsã of students and staff at the Bauhaus art college in an attempt to prove that the mind pulled certain colours and shapes together.

Jackson Pollock

Many other abstract artists have been influenced by psychology. Jackson Pollock began Jungian psychoanalysis in the late 1930s, in an attempt to cure his alcoholism. During these sessions, he created a series of drawings. Although Pollock moved away from this style of art, he continued to be interested in the processes of the brain. He said his famous drips were an example of an artist allowing his unconscious mind to determine the form of a painting.

Hearing colour

Much of Kandinskyãs art was an attempt to capture and represent how he experienced the world.

In addition to his interest in psychology, Kandinsky had a neurological condition known as synaesthesia, where stimulation of one sense produces experiences in another.

In Kandinskyãs case, he said he could ãseeã sound and ãhearã colour. He described a trip to the opera in Moscow by saying he saw, "All my colours in spirit, before my eyes. Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me.ã

Kandinsky lived with synaesthesia from childhood. He claimed that mixing colours in his paintbox created a hissing sound, with each colour on his palette making a different noise.

Learn more about this topic:

What is Art?

Following a day in the life of seven UK-based artists and designers as they tell us about their careers in art, crafts and design. Suitable for teaching pupils aged 11 - 14.

Inside the Human Body. collection

A series of short films looking at how the human body works.

Biology with Dr. Chris van Tulleken. collection

Doctor Chris van Tulleken introduces some handpicked biology clips from the ôÕÑ¿èÓ archive for use in the classroom.