Heaven is a noisy place

After months of Covid and confinement, Neil MacGregor and the Revd Lucy Winkett consider how community has traditionally been fostered by close contact with the saints.

The former director of the National Gallery and British Museum, Neil MacGregor, and the Rev Lucy Winkett, Rector of St James' Church, Piccadilly, find spiritual inspiration in the religious art of the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery.

After months of Covid and confinement, today's service considers how community — within society and across time — has traditionally been fostered by close contact with the saints.

For centuries the saints gave shape to the calendar and cohesion to communities. They helped individuals in distress, constantly affirming that we are never alone. They made the universal local and individual — and they were flawed humans, just like us. Virtually everybody had their own name saint, as did every trade, town and community. Looking at these paintings is like joining a really good party: You immediately recognise a lot of the guests, wearing not name tags, but symbols — and you know what bits of life they can help you with. They are shown with realism or fantasy, with admiration or humour, as people we have come to know well.

Crivelli’s Madonna of the Swallow is an intact Renaissance altarpiece. In its small, lower scenes, it shows the love of God among fallen humanity. On top of the altar perches a swallow — who builds her nest in the temple (Psalm 84) and who, for centuries symbolised the Incarnation, as out of the dirt and mud of her nest, she soars to heaven. The community of saints includes the natural world, as well as the living and the dead.

Finally, the saints are shown by Fra Angelico making music in heaven with all sorts of instruments — even bagpipes. Heaven is being with other people — and heaven is a noisy place.

Producer: Andrew Earis.

Last on

More episodes

Previous

Script

Music

When the Saints go marching in

Louis Armstrong

CD: 100 Hits Legends – Louis Armstrong (Demon Music Group)

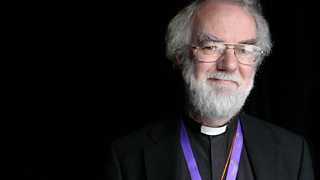

Neil MacGregor (in Trafalgar Square)

Good morning. It is the jazz classic that everybody knows, performed in New Orleans, on the banks of the Missisippi, and around the world.�� It is also one of the greatest of all spirituals, bringing an irresistible tune to the baffling Book of Revelation.��

Oh, when the Saints is of course a song of the Last Judgment, of the end of time, when sun and moon shall cease to shine, and a new world of justice and love will begin. ��But it is also very much a song of this world, of now, and it’s no surprise that it was popular with civil rights marchers of the 1960s, for it’s a hymn of hope, a song of community, social and spiritual, that promises a glorious togetherness, in which we all hope to find our place. ��But what does it mean to join the saints, to be in that number?

I suspect that we’ve all been thinking a lot about community over the lockdown months of isolation, separation, distancing and disruption - wondering what holds us together, what we can share, even when we can’t meet. And I think that we can find encouragement, ��perhaps even some answers ��by spending a bit of time with the saints, here, in Trafalgar Square, in the centre of London, where they march, sing and make music every day - in the magnificent paintings that hang in the building right in front of me, the National Gallery.

I’m with Lucy Winkett, Rector of St James’s Piccadilly, just up the road from here, and together we’re going to join the saints.

Lucy Winkett

It’s sometimes said that a saint isn’t someone whose life makes you think ‘gosh that looks like hard work. Saints are human beings who live their lives in such a way that you think ‘I’ll have what she’s having’.�� Saints are somehow especially alive.�� Many of them have suffered terribly of course; and many die for what they believe in. The Christian tradition will always insist that life in abundance is our calling: ��the saints are the ones who’ve said yes.

Let us pray.

God of time and eternity; in the middle of this global city, we thank you for the men and women we call saints whose lives speak to us across continents and centuries.�� Give us grace and energy to hear their voices today as our prayers join with theirs for the world Christ came to save. Amen.

Music

O quam gloriosum – Victoria

The Queen’s Six

CD: Journeys to the New World (Signum)

Reading

Revelation 19.6-8

Neil MacGregor (Walking into Sainsbury Wing)

We often talk of saints and their righteous deeds as of people who are distant or dead.�� but walking into one of the early rooms at the National Gallery reminds you that 500 years ago almost everybody lived with the saints on a day to day basis. You, your family and friends were named after a saint. A saint was the protector of your church, your town, your profession. Along with Easter and Christmas, it was the great saints’ feast days that marked the rhythm of the year and in a world before Bank Holidays, it was on the saints’ days that you were free from work, when the whole community joined in the festivities, in what we might now call street parties. The saints accompanied you through every stage of your life, guiding, helping and encouraging you and the people around you.

At home you would probably have small images of saints, perhaps on a bit of paper pinned to the wall, but there would be grander ones, like these paintings, in your church, and you would get to know the very well. So entering a room like this, you would have a sense of joining a gathering of friends. You know their stories and their legends, how they lived and died, what they suffered or achieved for the love of God. And you recognise a lot of them. St Peter is there with the keys given to him by Jesus, St Andrew carries the X-shaped cross on which he died, St Catherine holds the wheel of her martyrdom, ��St Francis patiently persuades a wolf to stop killing people, while over here St George less patiently slays his legendary dragon.

Music

Iste Confessor – Scarlatti

The Sixteen

CD: Iste Confessor – The Sacred Music of Domenico Scarlatti (Coro)

Lucy Winkett

In a world of few books, these are the stories that you know and that you tell your children. These are people that you know well – you live with their images, you speak to them every day. Saints are companions who reassure us that the path we tread, however challenging or alarming, is one that’s well trodden. In this vast and unknowable universe, we are never alone. ����

The word Sanctus/sancta from which we get ‘saint’ means holy– which in its turn means set apart. Saints are apart from us in some ways – they have lived ordinary lives in an extraordinary way - but the saints themselves are a human and humane crowd; full of opinions, unwise pronouncements, strange behaviour but ultimately examples of what human life can be. Sometimes because we experience them in two dimensions in a painting or a window, we start to believe that they themselves are too pious, a bit boring, perhaps obsolete in the modern world. But this couldn’t be further from the truth.

By turns courageous or foolhardy, awkward as well as inspiring, saints are human beings who somehow have an irreducible desire to travel towards the centre of things, close to the dwelling place of God.�� Like a journey to the centre of the earth, saints will come close to the heat and the dust of living at the core, where ‘the souls of the righteous are in the hands of God’. It’s a journey we can join.

Sainthood had a geography as well as a history: to travel towards their graves physically was a statement that you wanted to emulate them spiritually, and walk with them along the way. In one of her spiritual reflections, the 14th century English writer, Julian of Norwich, describes a saint as ‘a kind neighbour. To paraphrase the Beatles’ song, we’ll get by with a little help from our saints..

Music

Sanctus from Mass in A minor – Imogen Holst

The Choir of Clare College, Cambridge

CD: Imogen Holst – Choral Works (Harmonia Mundi)

Neil MacGregor (In front of Crivelli altarpiece)

The painting we’re standing in front of now shows a young, very serious, Virgin Mary, crowned, richly robed and seated on a throne, with the chubby infant Jesus on her lap. ��This is the court of heaven.�� She’s flanked by the almost life-size figures of two very familiar saints – two ‘kind neighbours, of our knowing’ - Jerome on one side, and Sebastian on the other. Painted in north Italy around 1490, it was designed to sit above an altar, in front of which the priest would say Mass, while the congregration��would kneel to pray and to receive communion.��

Music

Agnus Dei from ‘Westminster Mass’ – Roxanna Panufnik

Westminster Cathedral Choir

CD: Roxanna Panufnik – Angels Sing (Warner Classics)

Painted in sparkling greens and pinks, reds and gold, housed in its original carved frame, it’s called the Madonna of the Swallow, for the artist has lovingly painted the bird, with its red throat and forked blue-black tail, perched, far above all the figures, right at the top.�� It was painted by Carlo Crivelli : we know that, because, on the ledge below the throne, he has painted a little strip of paper, stuck on with six blobs of ceiling wax – just like a post-it note—with his name clearly written on it. ��He also proudly tells us that he is Venetian, though in fact he had to spend most of his life outside Venice, after being imprisoned for seducing a sailor’s wife. If you want to look at the picture, you can find Crivelli’s Madonna of the Swallow on the Sunday Worship webpage.���� ��

Now to our two holy helpers, the saints who stand with Jesus and Mary in heaven. On the left is Jerome, magnificently dressed in the red robes and hat of a cardinal. He was a great scholar, who around 400 retired to the wilderness to dedicate himself completely to prayer and penitence, and to translating the Bible into Latin. It was Jerome’s Bible that the Catholic church used for over a thousand years:�� so he holds up a little model church, resting on two large books, just to remind us - and the Christ Child, who from the security of his mother’s knee, looks apprehensively at this strange old man with a beard - just how much the church that we know rests on his, Jerome’s, work. ��Jerome knows he’s a celebrity, and he enjoys it. While Jerome was working, legend has it that a lion came to him, in pain because of a thorn in its paw: Jerome calmly and kindly removed the thorn, and the lion stayed with him ever after, a devoted household companion—and now here the lion is, with Jerome, in heaven, holding up his paw asking for him to help, just as we also ask him to help us with his prayers.

The old, contemplative Jerome is balanced on the right by the young, active Sebastian, a valiant ��Roman soldier, who switched his allegiance from the Emperor to Christ, was condemned to have arrows shot at him by his own soldiers, and was later, after much suffering, put to death. Because of that suffering, he became one of the saints whom you asked to protect you against the plague -- so across medieval Europe, Sebastian had a very large following indeed. Now in heaven, he’s dressed like an elegant young nobleman, solemn, a little shy, but stylish, his long blonde hair elaborately back-combed in what must be the latest fashion. In his right hand, he holds out an arrow, as he moves forward, to offer his suffering and his service, and the service of us, his followers, to the Christ Child.

The Christ Child is sitting on his mother’s lap, naked but for a few swaddling bands, and a coral necklace. But this is not just the infant Christ. His halo has in it, clearly visible, a cross, painted in bright red: this is the halo that marks the Christ who was seen by the apostles after the Resurrection. In heaven, in eternity, all moments in time are present. So we are looking at the child, but we see that this is also the Saviour, crucified, dead and risen:�� and his little hand holds, just manages to hold, an apple. It is the apple of the Fall in the Garden of Eden, the symbol of all the sin from which this child’s, this man’s, suffering has redeemed the world. Our two saints are talking to him, speaking for us, so that when, at the end of time, he comes to judge the world, he will have mercy on us.

Music

Ave Maria from ‘Adiemus – Songs of Sanctuary’ – Karl Jenkins

Polyphony

CD: Karl Jenkins – Motets (Deutsche Grammophon)

Reading

Revelation 21: 5,6��

Lucy Winkett

To group saints around Mary and Jesus is a familiar and common sight in Christian iconography. ��Christ and his mother are central of course, but neither is an ordinary human being. Saints are. Saints are closer to us, maybe less intimidating – and the community they are creating - for instance visually in this piece, is a community that always has space for the viewer to join. Our emotions are stirred by seeing them, and so our love is quickened. It’s not just a painting it’s an invitation to join in and remember that earth and heaven are but one breath away from each other.

The adult Sebastian and Jerome are in the presence of the child Jesus who died long before either of them were born. The painting in itself then upends time, but unifies it too: reminds us that the minutes and hours of our lives are a way of surviving the truth depicted in this scene; which is that life is eternal and love is immortal. It’s hard to be constantly aware of this reality so we live in a more manageable framework relating to the span of a human life and a human story. In this way, time itself is merciful and saves us from the colossal realisation of the nearness of God, that can overwhelm us when we realise the truth of it. Saints are human embodiments of this spiritual paradox. They take time into eternity and bring eternity into time.

Music

O God our help in ages past (St Anne)

Westminster Cathedral Choir

CD: Favourite Hymns – Westminster Abbey Choir (Griffin Records)

Neil MacGregor

Below the conversation in heaven, at the level that our eyes would be on if we were kneeling in prayer in front of the painting, are three little scenes, each about the size of a piece of A4 paper on its side. Like the large picture above, they also show us Jesus and Mary, Sebastian and Jerome, but this time not outside time and space in heaven, but when, like us, they were here, on earth. And what a contrast. No glowing colours, no gold here - earth is dull, drab fare by comparison. The figures are small, and we see them, like all human beings, confined to one, particular place, at one moment in need and in pain. In the chilly dirt of the Bethlehem stable, the new-born Jesus is kept warm only by the ox and the ass breathing over him. The saints on earth are isolated, as they confront their troubles alone. Jerome, half naked, beats his breast in penance for his sins, and has to share his desert retreat with dangerous dragons and snakes – as well as his faithful lion; Sebastian stripped to a loin-cloth, writhes in pain, tied to a tree, as arrows tear his flesh. This is the loneliness of life on earth. But above lonely earth is is the energising community and conversation of heaven. What separates the two worlds is death. What links them is devotion to Christ, and the saints, who by their steadfast keeping of the faith have already moved from this world to the next, who will be with us as we pass through death, and with whom we will ultimately – we hope – go marching in, to take our place with God and with them, in the company of heaven.

Music

Give us the wings of faith – James Whitbourn

Westminster Williamson Voices

CD: James Whitbourn – Living Voices (Naxos)

Lucy Winkett

Often the reason people are made saints is not only because of how they lived but how they met their death. How did they make that transition from earth to heaven?�� If they give up their lives as witnesses to the love of God, then they are the most venerated. The most precious gift we have been given is life itself, so to give it back to God is the highest possible calling. Saints then, show us how to live but can also teach us how to die. This altarpiece unites flesh and spirit, and is itself a place where all creation is present. Not only are creatures there - Jerome’s lion and Mary’s swallow - but also an abundance of fruit and flowers around them. And it’s no accident that this illustration is the backdrop to a priest holding up the host, the bread during the Mass. When the priest hold up the bread, the congregation looks directly at the body of Christ, united with the whole of creation.

Neil MacGregor

But what about that beautiful swallow, still perching on its ledge above the throne, and which gives the altarpiece its name?����

Listeners to Tweet of the Day know that swallows migrate thousands of miles to over-winter in Africa. But in Crivelli’s day, it was thought that swallows hibernated here, in mud, and so they became a symbol of the Incarnation – a heavenly being appearing in earthly clay -- and, as they could soar from earth to heaven, they were also a symbol of the Resurrection. Like the altarpiece itself, they inhabit and link two worlds. But for many viewers of the painting, ��Crivelli’s swallow ��would also have been ��a quotation,�� a visual echo of Psalm 84: the swallow builds her nest in the temple of God, which is to say, in the church itself:����

Music

How lovely are thy dwellings – Brahms

Tenebrae

CD: Brahms + Bruckner Motets (Signum)

Reading

Psalm 84

Neil MacGregor

In Crivelli’s painting, we catch a glimpse of heaven – even if it is only a small glimpse, with just two saints. The French philosopher Sartre famously said that Hell was other people. But no – being with others - the strength and the pleasure of community, is the essential feature of heaven, and ��the more people there are in heaven, the merrier. We are not meant to be alone. It is surely significant that Jesus taught us to pray not to My, but to Our Father.

Music

Sonata for 2 violins - Barbara Strozzi

Ensemble Poiesis

CD: Barbara Strozzi (Aeon)

Prayers – Lucy Winkett

God whose home in heaven is brought close to us on earth by the whole company of saints: we pray in tune with all creation in thanksgiving for the astonishing gift of life itself.

In remembering the lives of the saints across the world and across time, we pray in solidarity with all who suffer today.��

For those enduring the pain of grief, the desolation of loneliness, the bewilderment of diagnosis or the daily struggle of poverty and injustice.

May all who suffer on this day know deep in their souls, that they do not walk this path alone.

In union with Christ and the whole company of heaven, let us pray that God will bless us, in the words that Jesus gave us…

The Lord’s Prayer

Music

For all the Saints (Sine Nomine)

Salisbury Cathedral Choir

CD: Great Hymns from Salisbury (Priory Records)

Neil MacGregor and Lucy Winkett (walk to Angelico)

Just around the corner from the Madonna of the Swallow is a painting made in Florence about fifty years earlier by the Dominican friar, Fra Angelico. Long, narrow, and crowded, it gives us an astonishingly expansive, view of Christ in the Court of Heaven, at the end of time. It looks riotous.�� Clothed in white, radiant against a background of shining gold, stands Christ, bearing a halo and carrying a flag that both have the red cross of the Resurrection.�� He is surrounded by more than 250 rejoicing figures, none of them socially distanced, who are playing an astonishing variety of instruments – organs and drums, viols and tambourines and of course, trumpets.�� ��The noise must be overwhelming, exhilarating.

Music

O clap your hands – Gibbons

Cambridge Singers

CD: Faire is the heaven – Music of the English Church (Collegium)��

Lucy Winkett

The Book of Revelation from which we heard earlier gives us that rather riotous ways of expressing the peon of praise that’s constantly offered by the whole company of heaven. The saints teach us that prayer isn’t a start-stop thing that we ‘do’, it’s an orientation that carries us in life through death to life beyond. Whether we can ask the saints to pray for us was one of the more contentious arguments during the Reformation.

But in a world more atuned to our interdependence with the environment, now we will understand the eternal outpouring of prayer not simply to be human but offered by all that can give voice in creation; in union not only with Jerome, Sebastian and the others but with the swallow, the lion and all the created order.��

This eternal praise is continually outpoured by all of creation visible and invisible. All that happens when we pray is that we join something that is going on already, and will continue long after we’ve stopped.

The song of the saints in eternity won’t ever leave us mired in sentiment or intellectual musings, because it’s music that binds, like blood that flows through a living body. The song of the saints in eternity is a costly song, poured out to irrigate our earthly unity, rooted in the lived experience of those who suffered then and suffer still. Heaven is already here. A breath away. And when we sing with the saints, we can hope to be in that number…��

Music

When the Saints go marching in

Louis Armstrong

CD: 100 Hits Legends – Louis Armstrong (Demon Music Group)��

Broadcast

- Sun 6 Sep 2020 08:10�鶹�� Radio 4