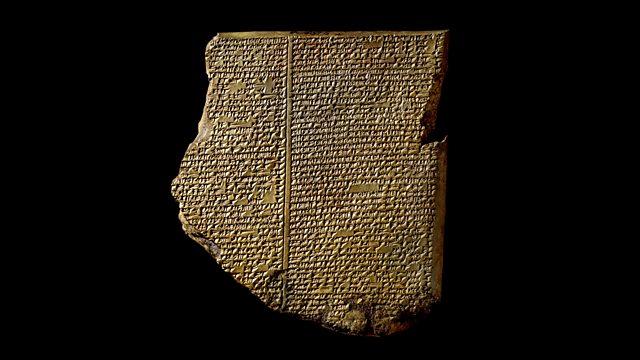

Flood tablet

Neil MacGregor describes the discovery of a clay tablet pre-dating the Bible that tells a similar tale to the one of Noah and the flood. The implications shook the Christian world.

A small tablet was found in modern Iraq and brought back to the British Museum. When it was translated, back in 1872, it turned out to be an account of a great flood that significantly pre-dated the famous Biblical tale of Noah. This discovery caused a storm around the world and led to a passionate debate about the truth of the Bible - about story telling and the universality of legend. In a week that looks at the emergence new ways of expression like literature and mathematics, Neil MacGregor introduces us first to the British Museum's provocative "Flood Tablet".

Last on

More episodes

Previous

You are at the first episode

![]()

Discover more programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects about communication

About this object

Location: Iraq

Culture: Ancient Middle East

Period: About 700-600 BC

Material: Ceramic

��

This Assyrian tablet tells the story of a plan by the gods to destroy the world by means of a great flood. Ut-napishti, like the biblical Noah, builds a huge boat to rescue his family and every type of animal. When this tablet was first translated in 1872 it caused a sensation. How could the similarity between the Mesopotamian myth and the biblical Flood story be explained?

A piece of the world's oldest literature

Mesopotamian poets had told versions of the story of the flood for 2,000 years before this tablet was written for King Ashurbanipal's Library. This version is part of the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh - the first great epic of world literature. Gilgamesh is a hero who sets off on a quest for immortality. He battles with monsters and ultimately must confront his own nature and mortality.

Did you know?

- When George Smith translated this tablet he was so excited he took his clothes off.

The power of knowledge

By Jonathan Taylor, Curator, British Museum

��

The Flood Tablet is a truly amazing object. Almost 150 years after its sensational appearance, it still captures the imagination like no other tablet. Perhaps even more amazing, though, is where it comes from — the Library of Ashurbanipal.

Ashurbanipal was a king of Assyria during the mid-seventh century BC. Fate had propelled him to become the most powerful man ever to have walked the earth. The exquisite reliefs that once decorated his palace in northern Iraq project the image of an accomplished hunter and warrior. But his library of clay tablets tells another story.

As a young boy Ashurbanipal had been trained not in kingship but in the scribal art; he was probably expected to serve as an expert advisor to his older brothers. When he became Ashurbanipal, King of the World, he used his power to assemble a library capturing the accumulated wisdom of all Mesopotamia.

In addition to great literature such as the Epic of Gilgamesh (to which the Flood Tablet belongs), there were hymns, prayers, rituals, dictionaries, magical and medical works, letters and treaties, as well as archives of legal and administrative documents. Most important of all were the manuals to help him divine the will of the gods, and thereby predict the future.

With the benefit of his unusual education, Ashurbanipal understood the power of knowledge. His library is that of a reflective and educated man, but also one designed to consolidate a king’s rule. His success is plain for all to see.

One of the most remarkable things about clay tablets is that they survive at all. Had the Assyrians written with parchment, nothing would have remained of this great library.

This in turn means that we have not just the words of the texts, but also the very clay manuscripts on which those texts were originally written. Among them are some that proudly proclaim: “I am Ashurbanipal,” writing the name on the homework of the future king.

Throughout his rule, Ashurbanipal retained his interest in scholarship. He boasted that: 'I have read cunningly written text the Sumerian of which is obscure and the Akkadian difficult to clarify. I have examined stone inscriptions from before the flood that are blocked up, sealed, mixed up.'

Letters between him and court scholars reveal discussions of omens and other complicated matters. The safety and prosperity of the empire depended on their correct interpretation.

The survival of Ashurbanipal’s library, albeit in fragmentary condition, has helped us to read and understand cuneiform writing, and given us a wealth of information about ancient Assyria. Even today, these tablets are the most heavily studied by modern scholars, seeking to piece together the broken fragments of the scholar-king’s library, and thereby reveal its astonishing riches.

The Flood Tablet: a first encounter

By Jacqui Honess-Martin, playwright

��

After a week of preparation in the library, my first impression upon seeing the actual Flood Tablet was one of bewildered anticlimax.

Tucked away in the corner of a gallery at the British Museum was a chip of stone no bigger than my hand. Dull, worn, unimposing and the lack of straight edges made it look sort of lopsided on its mount.

This had caused all that fuss? This tiny lump of rock had made a man called George Smith tear his clothes off and run screaming through the Museum when he found it? That brought him fame, fortune and a premature and agonising death in the middle of the desert?

Surely this was not the piece of stone upon which a story was etched, so controversial that the then Prime Minister attended the meeting at which it was first read. A story that cut straight to the heart of Victorian understanding and that still galvanises and splits society today. It really didn’t look as if was hung straight.

The deciphering of the Flood Tablet and the rest of the epic of Gilgamesh by George Smith was the subject for my next play. It didn’t even have a spotlight.

Nose pressed to the glass I squinted to make out the scratches and markings of the cuneiform. And then something dawned on me.

This tiny fragment had been found amongst the rubble of a fallen, ransacked city, 13 miles wide and abandoned for 2,000 years to the devouring desert sands. It had been found again amongst piles of broken pieces that had been shipped thousands of miles on horseback and by sea to the British Museum.

It had eventually been deciphered, through the poor light of the Victorian smog, by the lowliest of assistants, a man who taught himself to read its language. A man who realised instantly the incredible story locked into the tiny rivets and bird-like indentations that I now struggled to make out.

Nestled amongst the other tablets, it suddenly held a quiet humility. A self assurance that it would be found. Its story would be told. Again and again. The oldest narrative set down would endure. It didn’t need a bigger stand.

Taking in the gallery around me for the first time I realised everything in this incredible building was the same. The survival of every object against the ravages of time bestowed it with a sense of calm. Every single thing has been someone’s obsession, passion and joy. Every fresh understanding a controversy; every discovery a story. I hurried from the gallery, humbled, moved and anxious to begin my own.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Mon 8 Feb 2010 09:45�鶹�� Radio 4 FM

- Mon 8 Feb 2010 19:45�鶹�� Radio 4

- Tue 9 Feb 2010 00:30�鶹�� Radio 4

- Mon 29 Jun 2020 13:45�鶹�� Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Communication—A History of the World in 100 Objects

A History of the World in 100 Objects - objects related to communication.

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects