Bacon in Moscow

Stephen Wakelam's play for Drama on 3, Bacon in Moscow, reveals how Francis Bacon became the first major Western artist to have a solo exhibition in the Soviet Union.

This is the story of an extraordinary project, born of perestroika and glasnost, which challenged Soviet views on art and sexuality. The illustrations here are a selection of artworks which formed part of the exhibition.

All main images © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023. Photos: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

In the late summer of 1988 a convoy of lorries rumbled through Poland. At the USSR border they were met by an armed military convoy, accompanying them all the way to their venue in Moscow, a gallery space at the Central House of the Union of Artists. The contents of the lorries – near 30 paintings worth in excess of £20 million – happily arrived safely, having travelled the 1794 miles from London.

The paintings dated from 1944 to the present, all originating from a cluttered, seemingly chaotic space above a garage in South Kensington, the artist Francis Bacon’s studio. This was to be a retrospective of the artist’s work, nowhere near the scale of his exhibitions in London, Paris, and New York but notable as the first show by a modern Western painter behind the Iron Curtain in the history of the Soviet era.

‘A man with whom I can do business’ Mrs Thatcher had said, famously, of her meetings with the main instrument of the new openness, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev. This was the (brief) era of glasnost and perestroika. The tortuous and sometimes comic way in which this exhibition had come about is the subject of my play Bacon in Moscow.

Soviet art up to that point was more likely to feature bronzed girls on tractors and heroic, beaming workers with power tools, than these stylishly bleak canvases by an openly homosexual artist (homosexuality was illegal in the USSR).

As Andrew Graham-Dixon, one of the British journalists present at the press conference which preceded the show, shouted out: "Why, if you are homosexual here, are you locked in the gulag for 25 years?" The reply from Tahir Salakhov, First Secretary of the Union of Soviet Artists, was diplomatic: "We are interested in Francis Bacon’s art, not his private life."

In fact, there were no overtly homosexual pictures in the show, the most notorious of which (euphemistically known as "The Wrestlers" - two men entangled on a mattress) was safely back in London and hanging above its owner’s bed, Bacon’s fellow artist, Lucian Freud.

But Moscow did get one of Bacon’s famous "Screaming Popes" – Head VI (1949), a nightmare image based on Velazquez’s "Portrait of Pope Innocent X". In a key scene in the play we show how it was one of these studies, reproduced in black-and-white in a tattered art magazine, that led to the idea of the exhibition.

There was also a brand new "Study" (Bacon liked to imagine his paintings as only provisionally "finished"): Study for a Portrait of John Edwards. Edwards, a handsome cockney, shown part-naked and seated in a shadowy space on a chair that has mainly disappeared, was Bacon’s companion. This beautiful and oddly serene image served as the poster picture for the show, perhaps chosen for prominence in that it didn’t resemble Bacon’s more disturbing images. Like many of the paintings it’s an interior. Most – particularly the triptychs (there were 5 in the show, including Study for a Self Portrait (1985-88) – are claustrophobic, figures usually confined behind horizontal and vertical lines, often in some form of distress. They are not paintings you expect to see on a living room wall. Bacon reflects a little ruefully in the play that no one laughs in his paintings, "And yet I have been happy."

No one laughs in my paintings, and yet I have been happy.Francis Bacon, quoted in Bacon in Moscow

There are comparatively few exteriors, certainly no conventional landscapes. Jet of Water (1988), very recently painted, is a version of an earlier painting whose owner had been reluctant to let go of. There had been worries from a number of private owners about letting their pictures travel to the risky Soviet Union – "bandit country", as somebody says in the play. But there was change in the air, a hunger for art that escaped committees and censorship – even for Bacon’s brand of (exuberant) nihilism.

There were queues round the block for the show. In the building’s 6 large rooms, with its tired, shabby décor, the Russian public – some of whom had waited in line overnight – looked intently at the two-dozen-or-so canvases. "Not glancing and moving and talking to each other like a London crowd, but taking in everything that they could," as James Birch, the original author of the book Bacon in Moscow points out in his account of the event.

What did the Russians think? In the West the received wisdom was that Bacon, more than any other painter in the immediate postwar period, had responded in his art to the horrors and anxieties of his time. And Moscow, after all, was a city whose suburbs the Nazis had reached, an empire where untold millions had died, at the hands of Stalin as well as Hitler. Or did the gallery visitors simply see evidence of a sick psyche (which they might well have been ready for after all those smiling, heroic, propagandist figures)? One hundred million watched the Soviet TV programme tied in with the exhibition, whose catalogue (5,000 copies) sold out. Grey Gowrie, the former British cabinet and arts minister, who gave the keynote address at the press showing, speculated that the Russians might have more in common with Bacon than his own countrymen.

Art is a lie that makes us realise truth.Vincent van Gogh

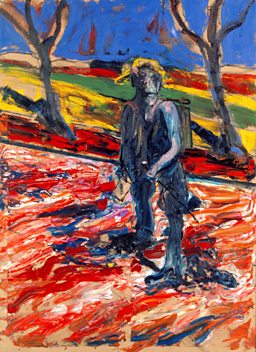

What Bacon shows is the dark side of life, the dark side of society. As a character in the play struggles to say, "He takes the skin off things." There’s a clarity in the artist’s unsentimental gaze. James Birch concludes his account of the show, noticing someone he had seen earlier in front of a particular painting: "As I went to leave the exhibition I passed the man in ragged clothes, still looking at Study for a Portrait of Van Gogh 111 (1957). He hadn’t moved." Van Gogh talked in his letters of art being a lie that makes us realise truth. It was an idea taken up by Picasso and impressed itself on Bacon.

There were folk, of course, who must have detested this bourgeois decadent painter, or who were unmoved, couldn’t see what the fuss was about. The entire Politburo and many Soviet dignitaries attended. This was a vast country, an empire in transition. The Bacon show – the very fact of its existence that September in 1988 – was a symbol of the whole concept of perestroika. Love or loathe the pictures, that’s what the fuss was about.

-

![]()

Listen to Drama on 3: Bacon in Moscow

The story of Francis Bacon’s ground-breaking 1988 exhibition in the USSR. With Timothy Spall and Luke Morris. Written by Stephen Wakelam, based on the memoir by James Birch.

Further viewing and listening on the �鶹��

-

![]()

Watch: Francis Bacon – Fragments Of A Portrait

Francis Bacon's paintings have been called sick and corrupt. He has also been hailed as the greatest British painter since Turner. This film study - Bacon's first appearance on �鶹�� Television - shows his work and its sources, and critically assesses his paintings. (1966)

-

![]()

�鶹�� Witness History: Francis Bacon in the archives

The painter Francis Bacon was known for his disturbing images and bohemian lifestyle. Over the course of his career he gave several interviews to the �鶹��.

-

![]()

The New Elizabethans: Francis Bacon

James Naughtie profiles the haunting artist of suffering, pain and death, most famous for his triptychs of the crucifixion and images of the screaming Pope Innocent X.

-

![]()

Start the Week: Francis Bacon revealed

Annalyn Swan, Russell T Davies and Mark-Anthony Turnage discuss the life and work of Francis Bacon with Andrew Marr.