Black History Month

To mark Black History Month, we have worked with illustrators to tell the stories of ten significant people and events in black British history.

Ivory Bangle Lady (circa 4th century AD)

The Ivory Bangle Lady's remains were discovered in 1901, buried near Sycamore Terrace, a residential street in a York suburb.

A shard of bone was discovered inside her stone coffin. It had the inscription SOROR AVE VIVAS IN DEO which translates as ‘Hail sister, may you live in God’, suggesting that she may have been a Christian.

A number of other luxury grave goods were also buried with her: some blue glass beads, fragments of five bone bracelets, silver and bronze lockets, two yellow glass earrings, two marbled glass beads, a small round glass mirror and a blue glass perfume bottle.

The most telling of her grave goods were two bracelets, one made of jet stone, which probably came from Whitby on the north-east coast of England, the other made of African ivory. The presence of the objects suggests that she was a woman of high social status, from the upper strata of Roman York, a settlement then known as Eboracum. Her story shows that Roman Britain was a society of far greater racial diversity than we might imagine.

Illustration by Sarina Mantle [@]

John Blanke and the Westminster Tournament Roll (1511)

It is thought that John arrived in England in 1501, as part of the entourage of Catherine of Aragon, who had come to London to marry Arthur, Prince of Wales and subsequently, after his death the following year, married his younger brother, Henry VIII.

Blanke performed at key state events. He even wrote to Henry VIII asking for a promotion and a pay rise. His skilfully worded petition was successful. Tudor records also show the King sent him a wedding gift of fine clothes.

He is not only the first Black Briton whose name we know but also the first for whom we have a portrait. That’s because among the events he performed at was the 1511 celebration to mark the birth of Prince Henry, son of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. The infant, who died ten days after his birth, was the couple’s second child and the second to have been lost.

The festivities of 1511 are recorded in the Westminster Tournament Roll, which is a sixty-foot illustrated vellum roll held today at the Royal College of Arms in London. Blanke appears twice on the Roll, shown on both occasions within the procession riding a grey horse and wearing an identical uniform to his five fellow royal trumpeters. The musicians’ costumes differ only in the fact that John Blanke wears a brown and yellow turban.

Illustration by: Olivia Mathurin-Essandoh [@]

The Somerset Case (1772)

James Somerset came to England from Boston, Virginia in November 1769 with his master, Charles Stewart. He converted to Christianity and after two years under Stewart, escaped. After just two months of freedom in November 1771, Somerset was recaptured.

He was put on board the Ann and Mary, a ship bound for Jamaica under Captain John Knowles, to be sold. Two days later, however, his Christian godparents Thomas Walkin, Elizabeth Cade and John Marlow obtained a writ of ‘habeus corpus’, which protects an individual from arbitrary imprisonment. Determined to fight for his freedom, Somerset enlisted Granville Sharp, a civil servant who had taken on the anti-slavery cause.

In 1772, Somerset’s case came to court. It was argued that no positive law relating to slavery existed in England and the law of Virginia was not applicable in England.

The case attracted much popular attention, especially amongst Britain’s black population, some of whom, as a result of the ruling, had reason to fear for their own legal status. Lord Mansfield, who was proceeding over the case was reluctant to give judgement but ruled that he could not determine whether a case could be allowed or approved by the law of England, meaning that Somerset was discharged.

The judgement appeared to grant freedom not just to Somerset but to all black people in Britain. Although this was not explicitly stated by Mansfield, it is nonetheless what most people took his judgement to mean.

Illustration by Ralph Akhigbe [@]

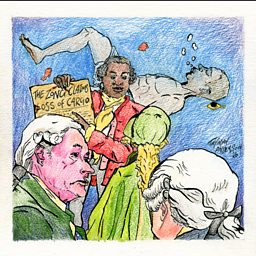

The Zong Massacre (1781)

What took place on the Zong in September 1781 brought to light a moral case against the slave trade in Britain.

The Zong sailed from Ghana with 442 slaves on board, around twice the number a ship of such size could transport without catastrophic loss of life.

Navigational errors meant the ship was running out of fresh water. Disease had broken out on the slave decks and among the crew.

To preserve supplies and protect their profits by ensuring that at least some of the slaves reached market in Jamaica alive, the crew of the Zong murderously cast 133 of the most vulnerable slaves overboard.

It was a massacre that stemmed from self-interest and incompetence. When the Zong arrived in Jamaica just three weeks later there were still 420 gallons of water on board. Just 208 of the 442 Africans who had been packed into the Zong at Accra were still alive.

The terrible incident was only brought to wider national attention when the insurance claim brought by the owners of the Zong against the ‘loss of cargo’ was refused. The first anonymous reports of the case were spotted in the English newspapers by former slave, writer and abolitionist Olaudah Equiano.

The insurance case came to court in 1783, when Granville Sharp (a civil servant who had taken on the anti-slavery cause) attended the case. Sharp employed a shorthand writer to attend court and record the testimonies given. They were then published, exposing some of the darkest secrets of the slave trade and outrage slowly built in the public’s consciousness.

Illustration by Taymah Anderson [@]

Sam Sharpe (Jamaica, 1831)

Enslaved Sharpe was a literate Baptist deacon, and a leader among the enslaved. In the weeks before Christmas 1831, he secretly planned a strike.

He and his followers pledged to refuse to work after Christmas unless they were offered wages.

The slave owners met the appeals of the strikers with bullets and bayonets. In response, the strikers became rebels. The cane fields and the great houses of the slave owners were set ablaze. At least twenty thousand slaves rose up. Some reports suggested the final figure was fifty or even sixty thousand.

The rebellion lasted two weeks and the captured rebels, including Sharpe, were executed. The uprising played a part in convincing politicians in Britain that the costs of maintaining slavery were too high and was one of the factors that led to the abolition of slavery.

Illustration by Habiba Nabisubi [@]

Sarah Forbes Bonetta (c.1843-1880)

As a child Sarah Forbes Bonetta was held captive by a West African King before being made a gift to Queen Victoria. Her name came from Captain Forbes, who agreed to transport her from Africa, and his ship the HMS Bonetta.

Queen Victoria wrote about their first meeting at Windsor Palace in November 1850. “her parents & all her relatives having been sacrificed. Capt. Forbes saved her life, by asking for her as a present... She is 7 years old, sharp & intelligent, & speaks English.”

Her life was transformed by the Queen’s readiness to accept her and ensure she received an excellent education, but also into adulthood her story was framed by mid-19th century British attitudes to race. These included the idea that for her health she could not stay in England and needed to be returned to Africa. When Captain Forbes published her story, he wrote of her talents and called her a “perfect genius”. Her story became wrapped up in the twisted debates where Victorian racial thinking meant such intelligence among Africans could be dismissed as an aberration.

Illustration by Lily Hammond []

"The Three Dikgosi Kings" (1895)

The three men were: King Khama of the BagammaNgwato people, Sebele I of the Kwêna people and Bathoen I of the Bangwaketse. Their journey radically changed the fate of the land and people.

They came to Britain on a mission. Their aim was to win over the British public in their struggle against Cecil Rhodes, who was threatening to take over Bechuanaland. Cecil Rhodes was the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony (in present day South Africa) and a diamond-mining millionaire who ruthlessly expanded British control in southern Africa.

The three kings were educated Christians who intended to outmanoeuvre Rhodes by appealing directly to the British people. With the support of their main ally, Reverend Willoughby, they toured the UK, attending meetings and dinners and gave speeches in towns and cities across the nation. On one occasion they were hosted by Queen Victoria.

The kings cleverly presented themselves to the British people as beneficiaries of the Victorian ‘civilising mission’ and were well received, becoming minor celebrities. The strategy paid off and through the tour they were able to win enough support to keep Bechuanaland out of the hands of Cecil Rhodes. The tour of the kings was one of the moments when Africans were able to influence colonial rule through diplomacy.

Illustration by Abbi Bayliss [@]

British West Indies Regiment (1915)

The British War Office, which was responsible for the administration of the British Army, initially rejected proposals of eager West Indian recruits. However, after much controversy, it formed the exclusively black labour battalion. The men were volunteers from British colonies of the West Indies. They served in Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

West Indian islands contributed more than £2 million in goods, oil and medical supplies to the war effort. In an eager effort to participate, men crossed the Atlantic Ocean, arriving in the United Kingdom on the SS Danube in May 1915. They were remanded by East London’s West Ham police and informed they’d need to sign up for the British West Indies Regiment (BWIR).

The War Office was intent on the BWIR not fighting against Europeans, meaning that many of the soldiers were limited to non-combatant roles yet still exposed to danger, as well as having to overcome segregation, discrimination in rank, housing and pay.

A total of 397 officers and 15,204 other ranks served in the BWIR – playing an important role in World War I.

Illustration by Shika Vowotor [@]

1919 Riots

Overshadowed by the memory of the war, the year 1919 was one of the most violent years of the twentieth century. There were riots and violent disturbances in nine cities throughout the United Kingdom, including Cardiff, Glasgow and Liverpool.

White working-class union workers and former servicemen lacked the resources to challenge shipping magnates. They largely blamed, targeted, and took out their frustrations on black and other ethnic groups who they saw as foreign competitors for jobs and for the attention of white women.

Hundreds were injured and another two hundred and fifty arrested. Five people were killed.

Liverpool, well known for its black population, experienced ferocious rioting in June 1919. There was an amalgamation of frustration and tension amongst black and white seamen. Police arrested dozens of rioters; black, Arabic and Asian businesses and homes were set ablaze. White rioters lynched Charles Wootton. He had fled from his house to escape. He was 24-years-old when he died and had served in the Royal Navy during the war.

Illustration by Toni Ojo [@]

The Bristol Bus Boycott of 1963

By the early 1960s there were around 3,000 people from the Caribbean and Africa living in and around the St. Paul's area of Bristol.

They were subjects of the British Empire who had come to Britain to find work. However black people were kept out of certain industries by what was called the 'colour bar'. The existence of the colour bar was common knowledge - it was both accepted and supported by unions. The Bristol Omnibus Company were notorious for operating a colour bar to prevent black people from becoming bus drivers and conductors.

In 1963 the young men in the illustration set out to take on the bus company and expose the unfairness of the colour bar. To do this they organised a boycott of the bus company. The Bristol bus boycott became a huge campaign that rallied support from many Bristolians and, in the end, forced the bus company to abandon its colour bar and employ black and Asian drivers. This success influenced the implementation of the 1965 Race Relations Act.

Illustration by Laura-Jay Doohan.