10 new things we鈥檝e learned about the Iraq war and its legacy

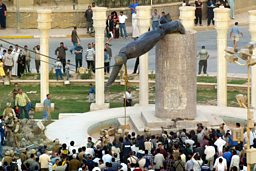

Twenty years ago a US-led coalition, including the UK, invaded Iraq. Within a few weeks Saddam Hussein’s tyrannical regime was toppled. But the consequences of the Iraq War have lasted many years.

In a new series, Shock and War: Iraq 20 years on, the 麻豆社’s security correspondent Gordon Corera has been speaking to some of those at the centre of the controversial decision to go to war and those affected by it.

Here are 10 new things revealed by the series.

1. The September 11th 2001 attacks were not the reason for invading Iraq

The terror attacks on the US – so-called 9/11 – may have changed some of the calculations but the desire for regime change in Iraq and to take action was already there.

“It came on to our agenda well before 9/11,” Sir Richard Dearlove, the head of MI6 (Britain’s foreign intelligence service) at the time, explains. “And although it looks as though 9/11 was the trigger for a change in policy [on Iraq], I don't think it really was.”

2. It wasn’t really about weapons of mass destruction

Weapons of Mass Destruction – or WMD – were the main public justification for war but behind the scenes they were seen more as the best way of selling it to the public.

“We were wrong on WMD. But I got to tell you, my personal belief, we would have invaded Iraq if Saddam Hussein had a rubber band, a paperclip, and somebody would have said, 'Oh, he's going to put your eye out – let's take him out.' That's my opinion,” says Luis Rueda, head of the CIA’s Iraq Operations Group at the time.

3. There were worries within MI6 about what was going on

When British spies inside MI6 first learnt of US plans for regime change, they reacted with surprise and doubt.

“One of the more senior officers in the service reacted by saying ‘crikey’; and I think it led to one of them actually warning Number 10 that it probably wasn’t that good an idea,” an MI6 officer working on Iraq at the time who asked to remain anonymous told the 麻豆社. They also believe weapons of mass destruction were not the real motive, just the public and legal justification. “I think from the government’s point of view it was the only thing they could find… I mean there was nothing else. WMD was the only peg they could hang the legality on.”

4. Relationships in Washington were "terrible"

Everyone knew there were tensions between more cautious voices like Colin Powell, the Secretary of State, and hawkish figures like Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary of Defense, Vice-President Dick Cheney and other neo-conservatives or neo-cons. But it turns out things were even worse than they looked.

Download and listen to Shock and War: Iraq 20 years on

"Essential listening..." Why the US and UK went to war in Iraq and its legacy. In Shock and War the 麻豆社's Security correspondent Gordon Corera speaks to those at the heart of the decision-making.

“I wouldn’t say the relationships were pretty bad – they were terrible,” says Richard Armitage, then the Deputy Secretary of State, who says the more hawkish voices often had not seen military service in the way he and Powell had in Vietnam. “The problem with the neo-cons is they needed to smell some cordite and none of them ever had.”

5. Tony Blair thought staying close to the US was vital

The Prime Minister at the time was worried about the US acting alone and wanted to maintain the UK’s relationship. He questions whether his successors have enjoyed the same influence.

He told Gordon Corera: “When I was prime minister, there was no doubt either under President Clinton or President Bush, who the American president picked up the phone to first. It was the British prime minister. But….today we're out of Europe and would Joe Biden pick up the phone to Rishi Sunak first, I'm not sure.”

6. UN Inspectors were shocked at what politicians were saying about WMD

UN Inspectors watched with surprise the confident statements by political leaders about WMD; but when they were given tip-offs by US and UK intelligence they found nothing. They drew a blank when looking for mobile biological labs.

”That was a big moment because that was a key plank of the case for war.” says one inspector. “It was just basically glorified ice cream trucks and a flatbed.”

“There were some cobwebs,” another inspector adds.

7. Tony Blair defends not taking a last-minute way out of war

In a video-conference call shortly before the war, in March 2003, President George W. Bush said he was worried Tony Blair could lose a vote in parliament.

He offered the UK the chance to back out of the invasion and only help with the aftermath.

I want regime change in Baghdad, not London, he said.

But Tony Blair turned it down: “I was sure that our alliance depended on us doing this together. Our own armed forces were very keen that we should play the part with them if we wanted influence…

"If Britain had left the alliance at that point... it would have had a significant impact on the relationship.”

"I will never think removing Saddam was the wrong thing to do."

Former PM Tony Blair "acknowledges mistakes" but is optimistic about the Middle East.

8. MI5 warned action against Iraq would increase terrorism

Security officials believe Iraq had an impact on radicalisation, fuelling the terrorist threat. Eliza Manningham-Buller was head of MI5, Britain’s domestic intelligence agency, at the time. “Our involvement in Iraq… gave Bin Laden his jihad,” she says, speaking of the leader of Al Qaeda. She says evidence was found in the video testaments of would-be suicide bombers that MI5 recovered in the UK. “Where we had insight into the motivations of those concerned… it was clear that this (Iraq) was a contributing factor.”

We got ourselves into this trap of never intervening even when we need to.Jonathan Powell

9. Have we learned the wrong lessons from Iraq?

Iraq came after a period of interventionism – often to deal with human rights abuses, such as in Kosovo – but it led to a sapping of confidence afterwards. For instance, parliament decided not to intervene in Syria in 2013 when the Assad regime used chemical weapons against civilians.

“We got too much confidence by the time we came to Iraq. Then Iraq happened. And after that, everyone thought, oh God, no, we mustn't intervene. And we got ourselves into this trap of never intervening even when we need to,” says Jonathan Powell who was Tony Blair’s Chief of Staff.

10. Iraqis haven’t got the democracy they were promised

“There is no way one can feel sorry for getting rid of Saddam Hussein,” says Iraqi-Kurdish politician Barham Salih. He has just stepped down as President of the country. But he acknowledges significant problems. “Do we have a viable Iraqi state today in Iraq? I tell you, no. It's work in progress, sometimes not in progress, I have to admit… because corruption is a crippling, crippling disease of the political system in Iraq today. Seventy percent of your population is below the age of 30. They don't give a damn about what happened under Saddam Hussein. They want the future.”

More compelling podcasts on Radio 4

-

![]()

Nazis: The Road to Power

The story of how in just 13 years, Hitler led a fringe sect with less than a hundred members and outlandish ideas to be the dominant force in German politics.

-

![]()

Putin

Jonny Dymond tells the extraordinary and revealing story of Vladimir Putin's life with the help of guests who have watched, studied and dealt with the Russian president.

-

![]()

Americast

Commentary on North America now with editor Sarah Smith, Today host Justin Webb, social media and disinformation correspondent Marianna Spring, and the 麻豆社's senior North American reporter, Anthony Zurcher.

-

![]()

Tunnel 29

The extraordinary true story of a man who dug an escape tunnel under the Berlin Wall.