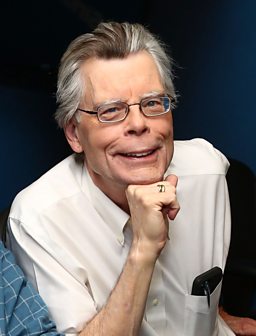

Ten things we learned when the Archbishop of Canterbury met author Stephen King

In the latest episode of The Archbishop Interviews, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, meets “The King of Horror,” Stephen King. The bestselling author of over 60 novels, including Carrie, The Shining and Misery, and hundreds of short stories, engages with the Archbishop over organised religion, disorganised religion and the very definition of evil.

1. King’s versatility surprises people

The Archbishop confesses that he didn’t know that King wrote The Green Mile and Shawshank Redemption. He’s not alone.

I chose to believe in God when I sobered up many years ago.

“The thing that I remember best about those books,” says King “is being in the supermarket one day and going up an aisle where this woman was looking at me, and she said, ‘I know who you are. You write all those scary stories. And that's all right. For some people, that's fine. I don't read those scary stories. I like uplifting things like that Shawshank Redemption.’ And I said, ‘I wrote that,’ and she said, ‘No, you didn't.’ So that was it. That was our whole conversation!”

2. Organised religion is – largely – anathema to King

King was raised a Methodist, where teetotalism was emphasised (“the girls would say ‘lips that touch alcohol shall never touch mine’”). He describes a general atmosphere of “good fellowship” at the church, but despite that and the fact his daughter is now a minister in the Universalist Church (his sons are both writers), King is circumspect about some organised religions.

“There are a lot of organised churches who have mistaken politics for part of their religion, where people get together and all believe in the same thing… once you start to group people together, someone's going to become an outsider and then there's going to be fights over religion and blood is going to flow.”

3. King’s faith and spirituality came from sobriety…

“Organised religion is one thing. Faith is another,” says King. Explaining his particular credo, he says: “What I care about is individual spirituality – the belief in a personal god, the god of your understanding - I'm very much in favour of that.”

This belief has been shaped by King’s battle against alcoholism.

“I chose to believe in God when I sobered up many years ago. They said to me, ‘The alcohol and the drugs are going to be more powerful than you are.’ And I could not seem to get sober. I got to a point where I felt that I just could not simply do this. There was a guy in a book I read who said: ‘Higher power? Buddy, there ain't no power higher than heroin.’”

4. …and literally put him on his knees

One of Stephen’s sponsors once asked him if he ever got on his knees to pray. “’I said, No, do you?’ And he said, reluctantly, as only a lapsed Catholic can: ‘Yes, I do get on my knees.’”

Through my meditations... I try to think of things that I really regret, things that really embarrassed me... the most important part is to remember those things and then move on with the day.

“At that point,” says King, “I decided that I would accept the God of my understanding. They keep it real simple, they say: ‘Get down on your knees in the morning and ask for help to stay away from drugs and alcohol for one day. And, if you do, when you get ready to go to bed, get down on your knees and thank the God of your understanding for the help that you got that day.’”

5. Meditations have been key to moving on

Now “straight and sober” for 33 years, King finds it easier to “live a moral life.” “When you do something that's rather shitty, you know that you've done it and you have to talk about it a little bit because the last thing that I want to do is to get drunk or to get stoned.”

Relieved that his grandchildren never saw him at his worst, King still has regrets such as being asked to leave his son’s Little League baseball game for drinking a beer in a paper bag.

“What I do is I go through my meditations, which are both at this point rather boring and also rather wonderful, and I try to think of things that I really regret, things that really embarrassed me… the most important part is to remember those things and then move on with the day.”

6. We want to stare evil in the face

“I think we find evil interesting,” says King, “and we find it necessary to see it and to understand it as well as we can so we can avoid it.”

“When I was probably 10 or 11 years old, there was a young man named Charles Starkweather who cut a bloody path across the Midwest. He shot and killed seven or eight different people [actually 11], and I read every story about him in the newspaper that I possibly could. My mother asked me: ‘Why are you so interested in Charles Starkweather? Do you admire him?’ And I said, ‘No, I don't admire him. But if I meet somebody like him, I want to know them when I see them.’”

7. The Exorcist is an optimistic film

Stanley Kubrick once called King during the filming of The Shining at Elstree Studios in the UK. He said, “Ghosts are basically optimistic, aren’t they?”

“It was seven o’clock in the morning,” recalls King, “I’m hung over and all at once we’re trying to have this philosophical conversation.” Kubrick believed ghosts were a sign of life after death, but King wasn’t convinced because it was based on Kubrick’s belief there was no hell.

However, King does see optimism in one of the most unlikely of places – The Exorcist. “I think that that is a very optimistic film because the little girl Regan is possessed by a demon. She didn't do anything wrong. It came in from outside. It's a supernatural entity like God.”

Stanley Kubrick called me to talk about ghosts...

Stephen King recalls a conversation about the afterlife, with the great film director.

8. Evil is part of the equation

Underlining why he can find solace in The Exorcist, King says: “The question that haunts me, and shows up in my books again and again and again, is how much evil comes from us? How much is bred in the bone and how much, if any, comes from outside?”

In his novel Desperation, he explores the duality of good and evil as embodied by spirituality and God. “There is a little boy in there who says ‘God is love, God is love.’ And at some point later on, he says, ‘God is cruel.’ And another character says, ‘Well, God is everything. He's both “God is love”, and “God is cruel”, and we have to accept that has to be part of our life.’”

“But acceptance doesn't equal just sort of standing back and saying let it happen,” qualifies King. “When Mr Putin invades the Ukraine, you have to do something about that. You have to be part of what I call the bright side of the equation.”

9. “If you keep a chip on your shoulder, it's going to give you a bad posture.”

In 1999, King was hit by a van when he was out walking near his home in Maine. The injuries he sustained required him to learn to walk again and caused a quarter of a century of recurring pain.

“Did I forgive Brian Smith for hitting me? No. Did I hate him? No. There was no great wheels of fate turning. He was just a bad driver. He lost control of his vehicle because a couple of dogs were fighting in the backseat over a cooler that had meat in it.”

“If you keep a chip on your shoulder, it's going to give you a bad posture.”

10. “Time slips through our fingers.”

Asked by the Archbishop where he finds the deepest experience of loving and being loved, King replies: “My family, my wife, my kids, my grandchildren, even my dog.”

“I try every day to love life itself – and I know that sounds like an empty platitude and people are probably going to see this and roll their eyes – but what I mean by that is time slips away through our fingers. Time is water. Yesterday I was 16, and today I'm 74.”

“I try at some point every day to look around myself, at the sky, at the plants, and try to find something that I can, not just be grateful for, but love for that one moment.”

-

![]()

Listen to The Archbishop Interviews Stephen King

Described as the “King of Horror”, Stephen King became a household name with novels such as Carrie, The Shining, and Misery. Those and countless others have been adapted for the big screen, including The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile, providing some of the most captivating moments in cinema history.

More deep conversations on Radio 4

-

![]()

The Archbishop Interviews... Tony Blair

The former PM reveals that the values and principles of his faith underpinned his career.

-

![]()

This Cultural Life: Brian Cox

Actor Brian Cox talks to John Wilson about the experiences and influences that have shaped his stage and screen career.

-

![]()

Sir Alex Ferguson: Made in Govan

From tenements to toolmaking to tournaments, Sir Alex Ferguson reflects on how his early life shaped his extraordinary career.

-

![]()

Desert Island Discs: Lyse Doucet

Lauren Laverne's guest is the �鶹��’s award-winning chief international correspondent.