Five amazing lockdown recreations of black people from historical portraits

Opera singer Peter Brathwaite used lockdown creatively.

Responding to the to reproduce a work of art using only household items, he embarked on an extraordinary project: to recreate as many artworks depicting black people as possible, posting the results on social media using the hashtag .

Over 80 artworks later, Peter’s remarkable recreations have made a huge impression, particularly in their relevance to the Black Lives Matter movement.

As part of Black History Month on Â鶹Éç Radio 3, Peter explores five of his recreations in depth, digging deeper into the stories of the characters he has brought to life.

He also shares discoveries he has made about himself, his Barbadian heritage and ancestry, through the processes of researching and recreating each portrait.

1. The man with the ship on his head

In the first episode we meet Joseph Johnson, the maimed Georgian street performer and former sailor whose act involved wearing an enormous model of a ship on his head. The original image is an 1815 etching by John Thomas Smith.

Peter says: When I found the etching of Joseph Johnson, I was on a bit of a roll on my recreative journey. I'd found a number of portraits that depict their black subjects as real people, not caricatures, and Joseph Johnson's was one of those. It was etched by John Thomas Smith in 1815 and appeared in a collection called Vagabondiana or, Anecdotes of Mendicant Wanderers Through the Streets of London; with Portraits of the Most Remarkable Drawn From Life.

It’s estimated that by the end of the 18th century, at least 10,000 black people lived in London, with a further 5,000 elsewhere in the country. Smith wanted to give as true-to-life a picture of London street life as possible, specifically documenting the capital’s homelessness crisis. Johnson’s appearance certainly was remarkable, though his story isn’t especially uncommon. Discharged from the Merchant Navy when wounded, he wasn’t entitled to a seaman’s pension, nor could he claim an allowance from the parish - because he was born abroad. So he had little choice but to take to the streets...

-

![]()

The man with the ship on his head

🎧 Listen on Â鶹Éç Sounds

2. The boy with the monkey on his back

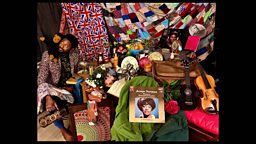

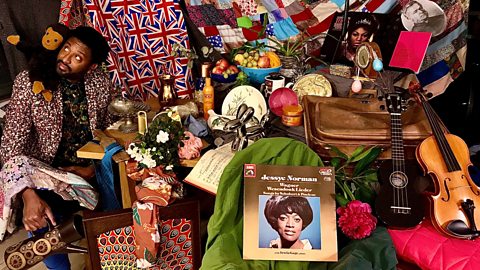

Peter casts himself in the role of the anonymous boy who appears to the left of the extravagant 17th-century oil painting, The Paston Treasure. This still life by an unknown artist of the Dutch school, now housed in Norwich Castle, was created in the early 1670s and documents a wealthy family's lavish collection of objects.

Peter says: A Twitter follower introduced me to this painting. It was a nudge that came fairly early on in my Getty Museum Challenge series. It was only a few days into my quest to Rediscover Black Portraiture, and the dressing-up pile was already taking on a life of its own. I think I was subconsciously gearing up for a big one - and so, the Paston Treasure was just the ticket.

It really is a remarkable painting - and pretty famous too, in art history circles. But while much scholarly attention has been paid to its technicalities, the family that commissioned it and the provenance of the objects piled high on the table, relatively little has been said about the black figure who simultaneously seems both to command the scene and exist on its margins.

When I recreated this painting, this sidelined figure had to be centre stage. That’s the point of my project, after all - bringing marginalised black figures of art history into the foreground. So I cast myself in the boy’s role.

Stepping into the anonymous black man’s shoes would bring his reality and his truth into the picture: creating a scene where his culture could shine, amaze and be treasured.

How to recreate an epic artwork using household objects

Peter Brathwaite's own family history influenced this recreation of The Paston Treasure.

-

![]()

The boy with the monkey on his back

🎧 Listen on Â鶹Éç Sounds

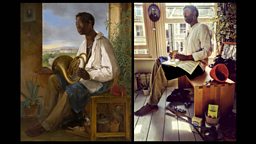

3. The man with the French horn

In the third episode of Peter's series, we meet Emmanuel Rio, a horn player and gardener in the employ of Emperor Francis I of Austria, as depicted by Austrian artist Albert Schindler in 1836.

Peter says: I came across Emmanuel’s portrait before I knew his name and story [until very recently, the figure was anonymous], but I was immediately drawn to him, as a fellow musician. It’s an intimate scene that on closer inspection is brimming with details that capture a crucial moment in Emmanuel’s extraordinary journey - from enslavement in a Portuguese colony to court service in Austria and his eventual abandonment.

There’s real tenderness in this painting. The level of detail implies that Rio was well-regarded and a good, devoted subject. But that’s just what he was: a subject. There’s no getting away from the fact that Emmanuel, though technically free at this point in his life, was never able to determine his own fate. His dependence on the imperial family and their subjugation of him is plain to see in his remarkable facial expression.

Today, as I look at Emmanuel’s portrait, I chart the line from then to now. As a black classical musician, I think of the progress made and the work that still needs to be done to make my own industry truly diverse. Emmanuel Rio’s story is heartbreaking. But, I’m fortified by the fact that this portrait exists. He was there. I see myself represented. I am here, now, and so is he, in a way, because he has a face and he has a name.

-

![]()

The man with the French horn

🎧 Listen on Â鶹Éç Sounds

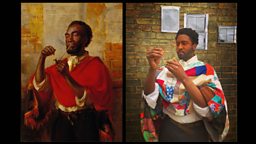

4. The man with the pipe

In episode four, Peter recreates Thomas Stuart Smith's The Pipe of Freedom, a portrait of an enslaved African man who has just been granted his freedom following Abraham Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

Peter says: There it is, in black and white - President Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. It’s pasted to a wall and partly covers a placard announcing the sale of slaves. For this formerly enslaved African, the moment of realisation is joyful, but also heavy. It’s the realisation that everything he’s ever known has been shattered. A whole community based on the social, political and economic organisation of white masters and black slaves is no more.

After my initial step into Smith’s painting, I emerged thinking about the stack of family history records I’d been collecting. Addo, my grandad’s grandad’s grandad, had been kidnapped in Ghana, crammed onto a slave ship and forced to work the sugar plantations of Barbados, later serving as a favoured house slave. Finally, in 1817, at the age of 75, he was officially “released, manumitted, enfranchised, set free and forever discharged of and from all and all manner of servitude, slavery and bondage whatsoever…” His freedom cost £50, most probably paid from his own pocket.

For me, recreating and reimagining this portrait became about honouring Addo’s memory and his long road to freedom. It was freedom that came so late in life that he only got to enjoy it for 14 years.

-

![]()

The man with the pipe

🎧 Listen on Â鶹Éç Sounds

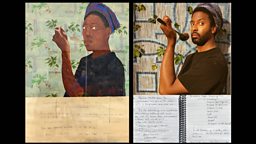

5. The woman with the spoon

In the fifth and final episode of Peter's series, we meet artist Sonia Boyce, whose 1982 self-portrait Rice n Peas celebrates her Black British identity through the medium of food.

Peter says: "My mother used to shout at me every meal time because I ate so little and so slowly… she was worried because I was so thin." These are the words handwritten on the lower portion of Rice n Peas, a self portrait by Sonia Boyce - a British artist of Barbadian heritage, like me. Surrounding this jotted-down recollection are scribbled names of familiar foodstuffs. It’s a British Afro-Caribbean buffet banquet!

Above the faded scrawl on its stained, scuffed paper panel is Boyce herself. Boyce’s portrait is striking and complex. Spoon clutched awkwardly in her raised hand, she looks out to us, lips closed, eyes wide, hair tied. She has recreated herself in a stylised, almost caricatured way. But there's a defiance in her penetrating gaze at the viewer, as if she's saying: "This is me, here. Have you got a problem with that?"

She's dictating the terms of how we view her, how we judge her, how we know her. In her image, I see all the anonymous black figures I’ve encountered on this journey of Rediscovering Black Portraiture: silenced and unable to articulate themselves in the face of whiteness. Through this portrait, Boyce reclaims the “space” of the portrait, making it truly hers. Ours. Mine.

-

![]()

The woman with the spoon

🎧 Listen on Â鶹Éç Sounds

Opera singer Peter Brathwaite reveals his extraordinary lockdown project, Rediscovering #BlackPortraiture, in a five-part series of The Essay. Listen now on Â鶹Éç Sounds.

-

![]()

Listen to all five episode of Discovering Black Portraiture

Peter Brathwaite meets and recreates a host of black characters as depicted in artworks over the centuries.

-

![]()

Thinking Black

Writer Colin Grant explores the fascinating stories of five individuals who challenged the boundary of race.

-

![]()

Mayflower Portraits

Five writers reflect on the impact of the Pilgrims setting sail on the Mayflower 400 years ago.

-

![]()

29 things that only people who collect pebbles will understand

Can't seem to stop picking up pebbles? You're not alone – although it can sometimes feel that way.