This is what coronavirus will do to our offices and homes

One day, the virus will subside. It could be eradicated. But even then, life will not simply return to the way it was before Covid-19. Spurred on by the coronavirus crisis, architects have been rethinking the buildings we inhabit.

Scroll down to find out how the future might look.

Meet Laila.

It's 2025 and she works from home four days a week. It's been that way since the 2020 lockdown.

It's 06:30 and she's on her way to work.

Laila arrives at her office building at 07:00. Start times at the company where she works are staggered to minimise the number of people arriving at the same time.

Her "office days" are mainly for meetings. Gone are the days when she'd head into the office to work at a screen. She can do that at home.

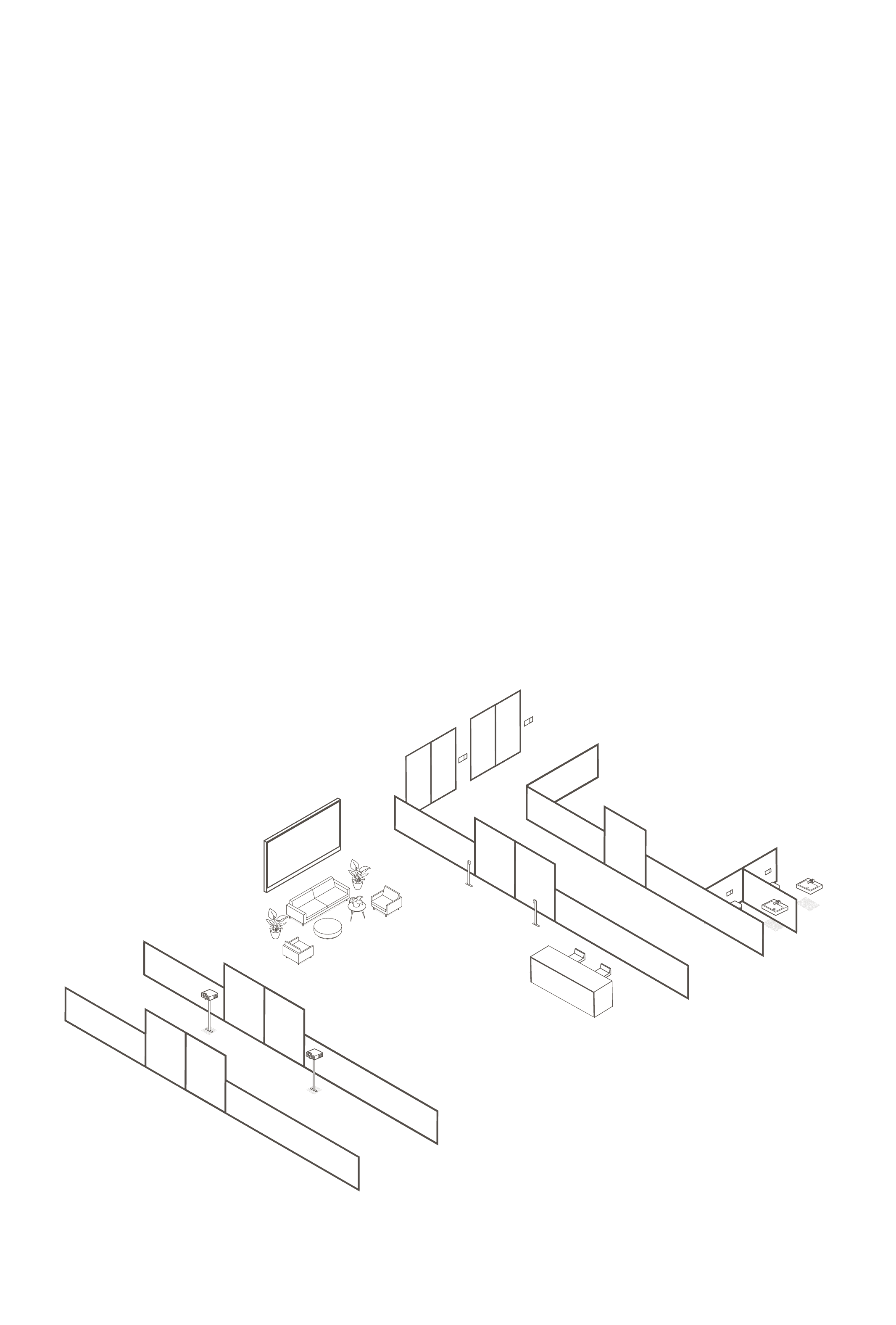

Laila's employer used to share a much larger office building with several other companies. Now they're in a smaller, newly-refurbished premises all to themselves.

On the ground floor Laila pauses in front of a thermal body scanner to check her temperature is normal. Today it's 36.5C. She passes.

A camera, used for facial recognition, identifies her as a staff member and a security barrier opens. At no point does she touch anything. Laila is on a contactless pathway.

The lift to her office on the fourth floor is voice-activated. Touchless technology has replaced grubby buttons. The maximum occupancy is two.

On the fourth floor she walks down the corridor and through the door. Both are wider than before, made that way to keep staff further apart and reduce the chances of a virus being transmitted.

At the door Laila uses a hand sanitiser. She's so used to it now that she doesn't even think about it.

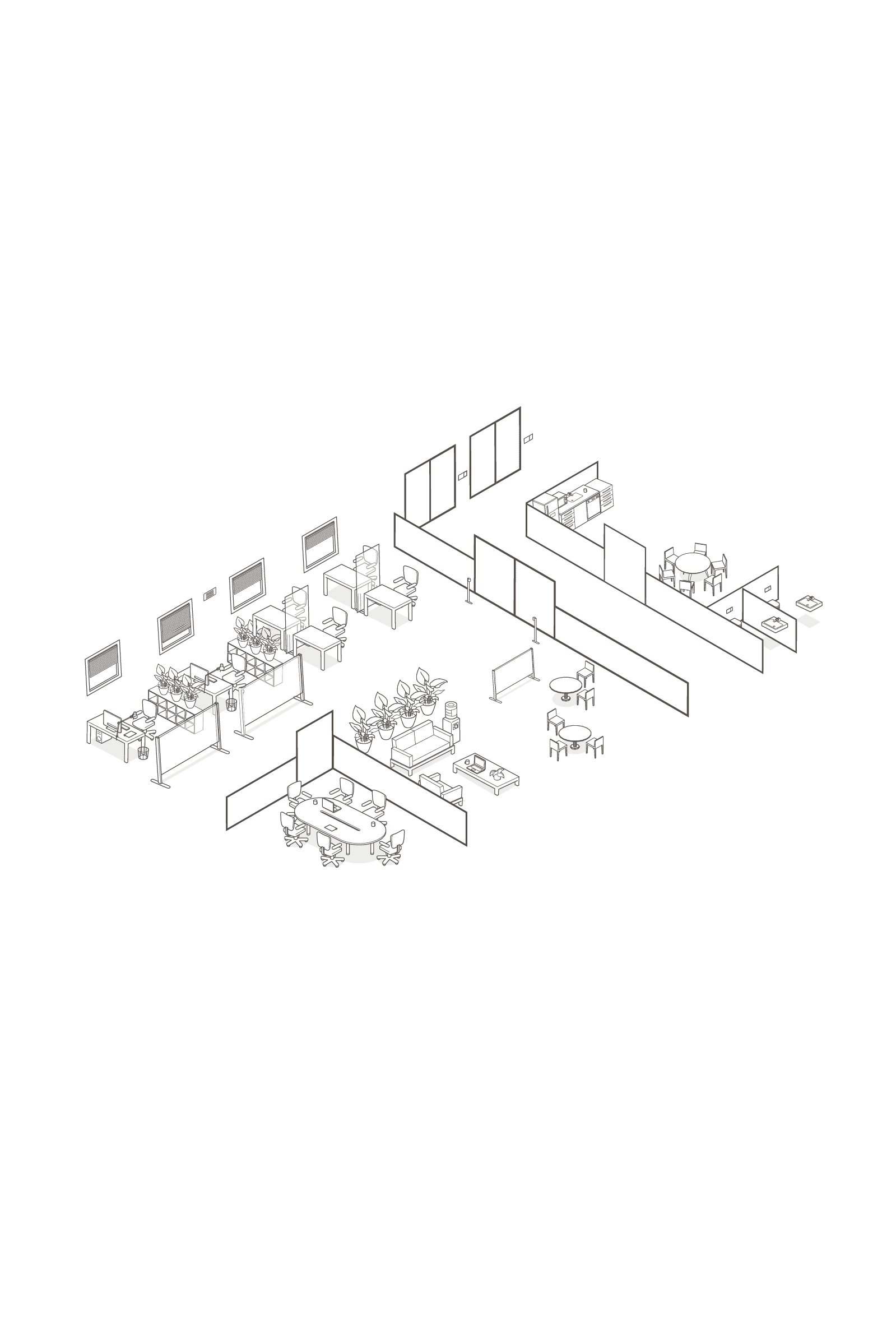

She sits down at the desk. Much of the furniture - as well as wall panels and facades - is made from antimicrobial material. It's easier to clean and harder for bacteria to stick to.

Laila makes a coffee in the kitchen area where the worktops are also antimicrobial. The handles on the drawers and cupboards are made of copper. It's a costly but naturally microbe-repellent material.

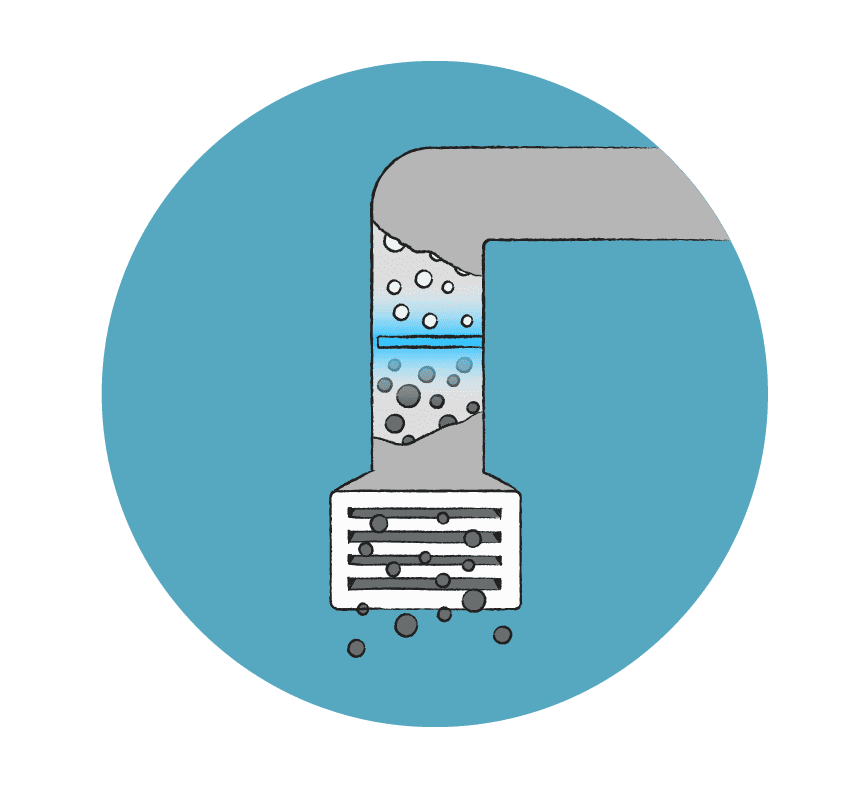

The air conditioning system uses UV light to kill pathogens. It also reduces the humidity to help prevent germs multiplying, responding to a stream of data from sensors fixed around the building, and wearable sensors used by staff.

Laila's office used to be completely open plan. Now she's partitioned off. To her left there is a clear plastic screen so that she can at least see her colleagues. The screens are removable, bolted into fixtures in the floor. They go up if there's the threat of an outbreak, but come out if the threat subsides.

In front of Laila's desk, the separation is done with plants. The staff got fed up with plastic everywhere a couple of years ago. They said it made the office feel like a hospital. Laila prefers the plants.

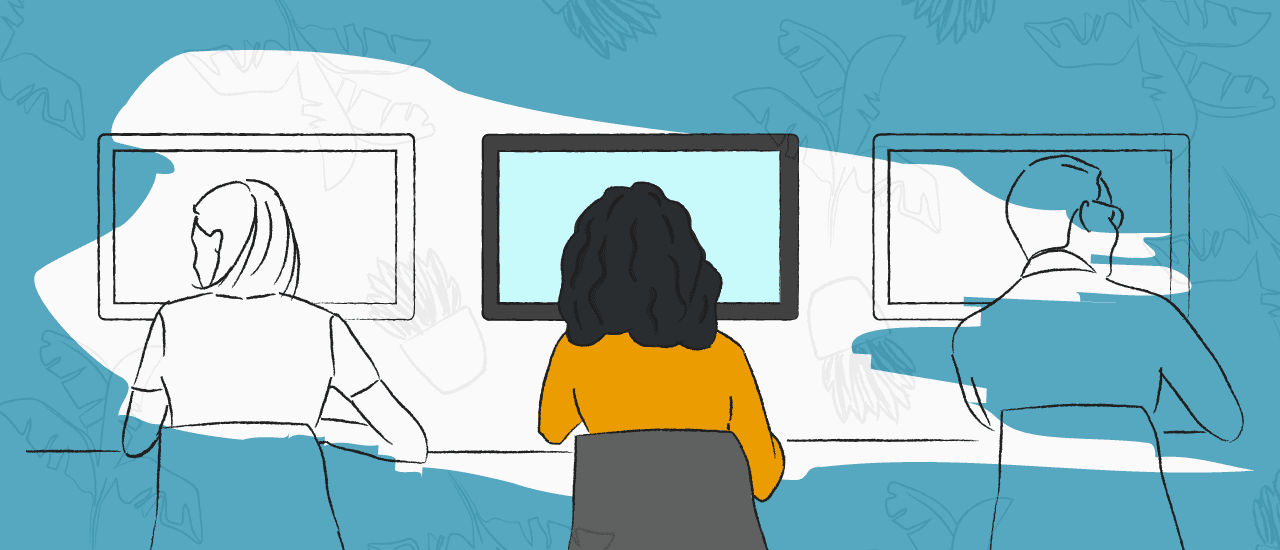

Laila's morning is spent in a meeting about a new project. It's face-to-face with colleagues - but all at a safe distance. The only reason Laila goes into the office now is for this kind of interaction - in which meeting people in real life produces better results than seeing each other online.

It's 16:00 and time to go home. Laila moved to the suburbs with a friend after the lockdown in 2020. It's a longer commute, but she doesn't mind as it's only once a week.

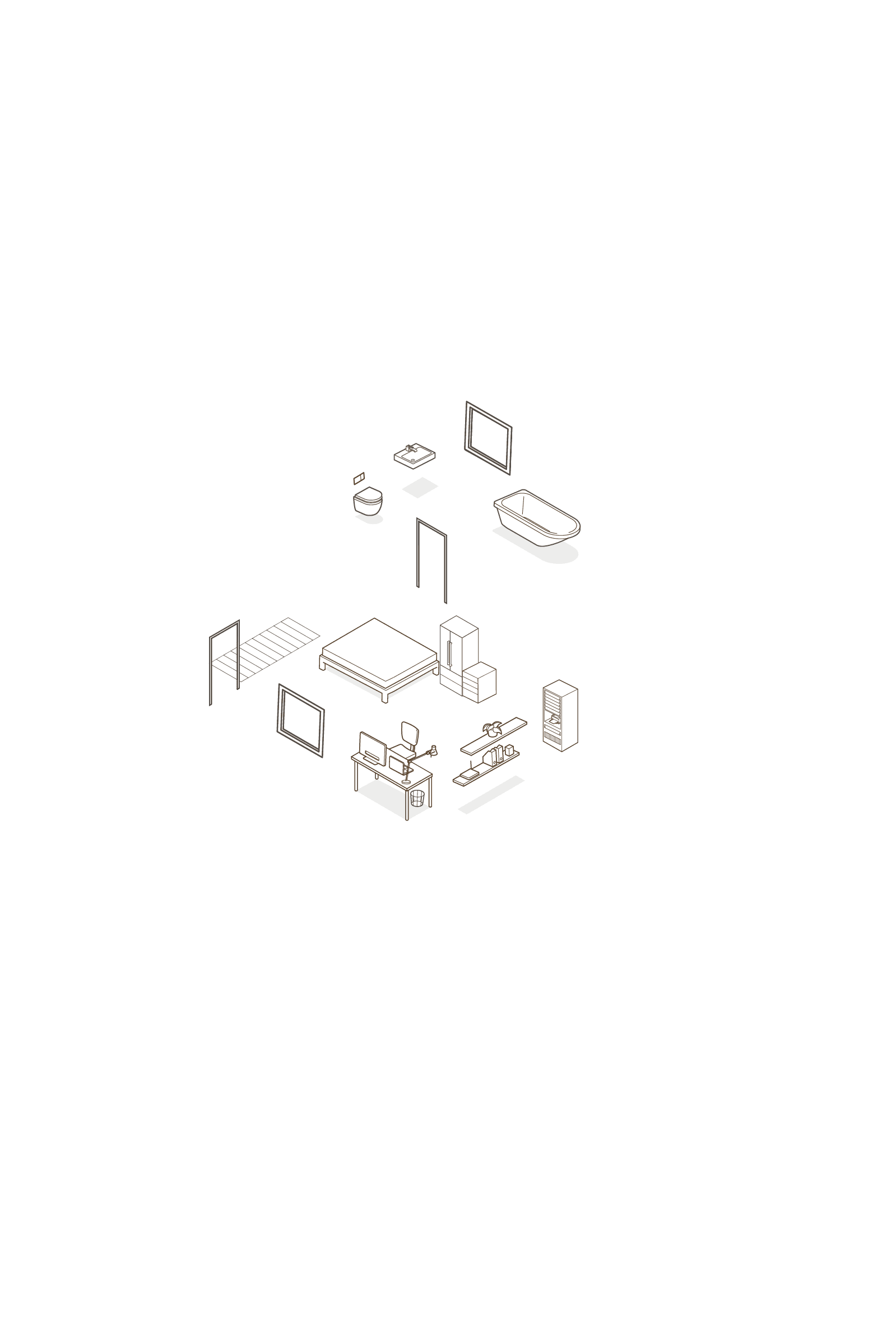

A bigger home meant more space. When the lockdown came she thought working from home would only last a few weeks, and that she'd manage with a laptop on the kitchen table.

But when weeks turned into months, and months turned into years, she knew she would need a home office and her old flat in town was nowhere near big enough.

She now works in an upstairs room. There's a new standing desk, a properly adjustable office chair and storage for documents.

She never realised, before, how important it was to have good lighting, so she had spotlights installed in the ceiling and bought a proper desk lamp.

Laila is saving up to replace the double glazing. She's near a big road and she needs to concentrate hard when she's working - sound-proofing is an issue she hadn't anticipated.

She thought about a loft extension and building an office in the garden, but decided on the bedroom office option for now.

It's been quite a change for Laila - and millions like her.

Not everything will change, of course

While Laila made changes to her life relatively quickly after the pandemic hit, architecture, in reality, moves slowly. Buildings typically take five years to design, finance and construct.

Many people can't afford to move house - or spend money on home improvements. And in the teeth of a recession, many employers won't have the money to relocate or reorganise.

If Covid-19 dies out in the coming months and a vaccine is found quickly, many homes and workplaces could return to something like "normal".

But aspects of Laila's imaginary life may become reality for many of us, particularly if there are continued outbreaks and no vaccine is found.

Financial pressure to change

Many architects believe a major shift towards working from home will be the most significant impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the built environment.

Why? The short answer is money, says Prof David Burney, who served as New York City commissioner for public architecture under Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

"Companies can cut their bills for office space dramatically by increasing the number of staff working from home – and they will do it," he says.

"We're already seeing some in the commercial real estate business in a state of panic. They can see the demand for office space declining."

The shift away from the city

"I think we could see a lot of existing buildings become unmarketable," says Hugh Pearman of the Royal Institute of British Architects (Riba).

Large-scale office spaces, particularly in high-rise buildings which are hard to modify, are already becoming less attractive.

"And there will be pressure to flee the city," he says.

Mr Pearman points out that health concerns have driven key architectural developments in the past.

Worries about disease and poor air quality triggered population movements away from city centres in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and the growth of suburbs was a direct consequence.

Making the home work

If pre-Covid homes were all about relaxing and recharging, post-Covid homes will be part home, part workplace, says UK architect Grace Choi.

"Many more people are going to want more space in their homes to work, or at least some versatility in the space that they have. We're all going to need to configure our space in a more intelligent way."

Ms Choi says her practice is already getting many more inquiries from builders about homes with office spaces and garden studios, as workers find that perching at the kitchen table with a laptop just doesn't cut it.

Homeworking doesn't suit many jobs, of course, and thousands of offices are here to stay. Architects envisage that creative thinking and new technology will help keep them relevant.

The rise of touchless tech

"The days of sitting there hammering away on a laptop are gone - you can do that from home," says Dale Sinclair, architect and director of innovation at AECOM.

"What's really exciting is that going into the office will be for collaboration, generating ideas with colleagues."

Mr Sinclair is one of the many architects predicting vastly more automation in offices, particularly "touchless technology" or "contactless pathways" and a greater use of data.

"Buildings are going to have a huge amount of technology: people using their phones to navigate through them, face recognition, voice activation. And we'll see many more robot assistants and sensors picking up data," he says.

"This whole area is going to really take off. We're already using this technology in hospitals – and Covid-19 is massively accelerating the move towards using it in other places."

Information from fixed and wearable sensors could be used to adjust air temperature and humidity in the fight against some pathogens.

Air conditioning systems using UV light to kill bacteria and some viruses are already in use, with light sources in the coils at the centre of the system or in the ducting.

Can open plan survive?

The downside of the open-plan office is obvious during the pandemic, but some experts believe that open plan could survive if measures to limit interaction are in place.

Where partitions are essential, architects and designers are trying to minimise their negative impact on social interaction.

Can they be removed when there's little threat, but reinstalled if there is an outbreak?

Can they be clear, rather than opaque, so that staff can still have eye contact with workmates?

For Ben Channon, head of wellbeing at Assael Architecture, biophilia - our in-built affinity with the natural world - is the way forward.

"We can use rows of plants to separate people. People are quite scared – they're not going to want to come back to a plastic cubicle that smells of bleach. In the right circumstances plant screening can be a much better solution - and can also help with air quality."

Mr Channon advocates using naturally antimicrobial materials like copper and its alloys, in high-touch areas like door and drawer handles.

Copper is expensive but "businesses are seeing the cost now of what happens when they don't have these things," he says.

The shape of things to come

While remote working for many may be the legacy of Covid-19, coming together in the real world is still fundamental to human psychology, says Sadie Morgan from London-based firm dRMM.

"Taking risks and creativity, essential for businesses, generally happens in groups, real groups - not in a virtual space - when you can see people directly and be in the same space."

Grace Choi agrees. "We shouldn't underestimate the need to get together to exchange ideas.

"We miss body language, cues for when to speak, fluid conversation and the connections between us."

What's the future for the office?

What's the future for the office?

Fujitsu announces permanent work-from-home plan

Fujitsu announces permanent work-from-home plan

How cities might change if we worked from home more

How cities might change if we worked from home more