How a single locust becomes a plague

Vast swarms of desert locusts that tore through East Africa and beyond earlier this year are breeding again, with a second wave of insects now threatening food supplies and livelihoods. It's the worst infestation in a quarter of a century. How did it get so bad?

A desert locust like this - a type of grasshopper - usually likes to live a shy, solitary life. It develops from an egg into a young locust - known as a hopper - and then into a flying adult. It's a simple, if unremarkable, existence.

But every now and then, desert locusts undergo a Jekyll and Hyde transformation. When they get crowded together - such as on diminishing areas of green vegetation - they stop being solitary creatures and become "gregarious" mini-beasts.

In this newly-sociable phase, the insects change colour and form groups that can develop into huge flying swarms of ravenous marauding pests.

Such swarms of locusts can be huge. They can contain up to 10 billion individuals and stretch over hundreds of kilometres. They can cover up to 200km (120 miles) in a day, devastating rural livelihoods in their relentless drive to eat and reproduce.

Even an average swarm can destroy crops sufficient to feed 2,500 people for a year, according to the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

The last major upsurge - a sharp rise in the number of swarms - in West Africa in 2003-05 cost $2.5bn in harvest losses, according to the UN.

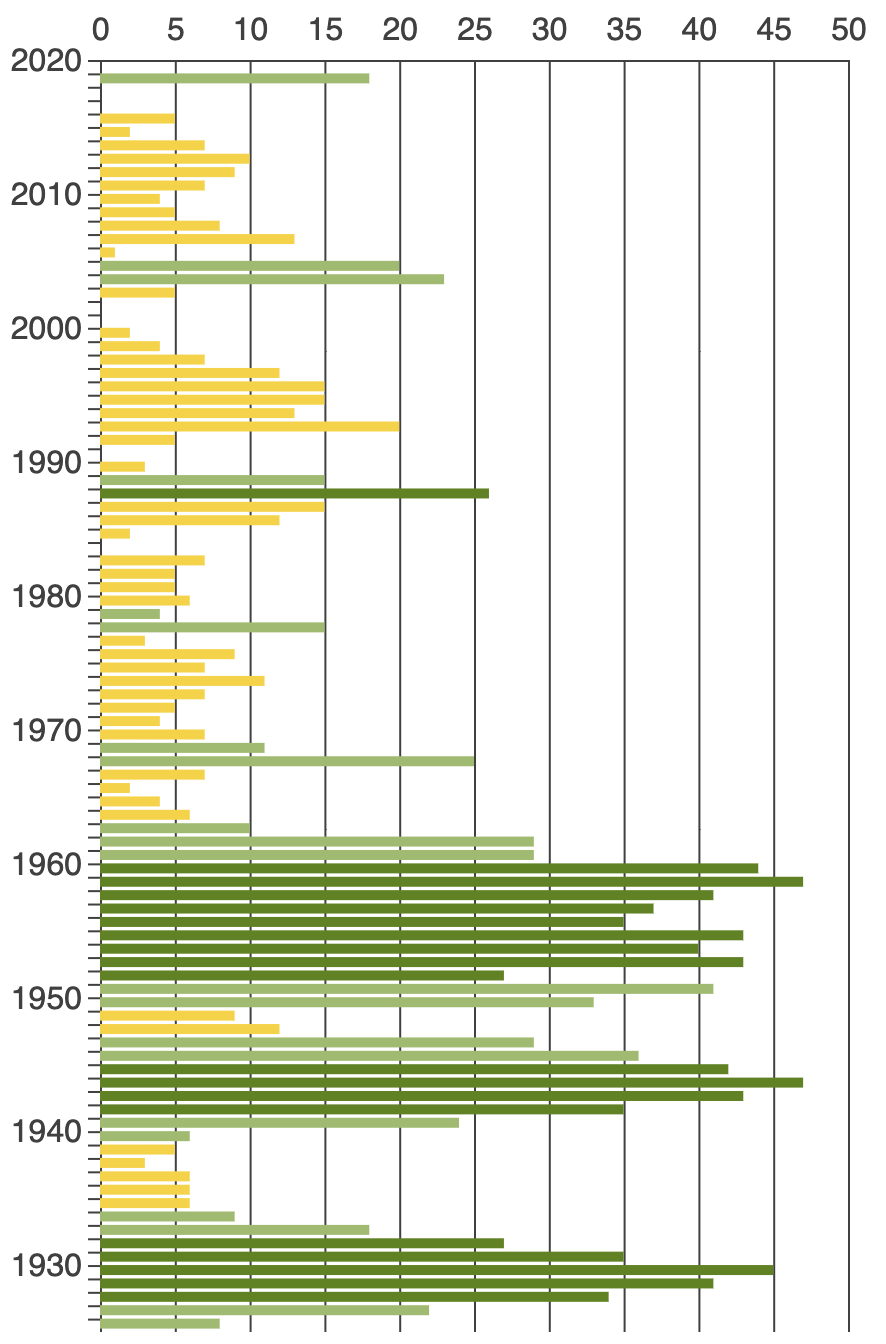

But there were also large and damaging upsurges in the 1930s, 40s and 50s. Some of them spanned multiple regions, reaching the numbers required to be declared a "plague".

Overall, the FAO estimates the desert locust affects the livelihood of one in 10 people on the planet - making it the world's most dangerous migratory pest.

A desert locust like this - a type of grasshopper - usually likes to live a shy, solitary life. It develops from an egg into a young locust - known as a hopper - and then into a flying adult. It's a simple, if unremarkable, existence.

But every now and then, desert locusts undergo a Jekyll and Hyde transformation. When they get crowded together - such as on diminishing areas of green vegetation - they stop being solitary creatures and become "gregarious" mini-beasts.

In this newly-sociable phase, the insects change colour and form groups that can develop into huge flying swarms of ravenous marauding pests.

Such swarms of locusts can be huge. They can contain up to 10 billion individuals and stretch over hundreds of kilometres. They can cover up to 200km (120 miles) in a day, devastating rural livelihoods in their relentless drive to eat and reproduce.

Even an average swarm can destroy crops sufficient to feed 2,500 people for a year, according to the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

The last major upsurge - a sharp rise in the number of swarms - in West Africa in 2003-05 cost $2.5bn in harvest losses, according to the UN.

But there were also large and damaging upsurges in the 1930s, 40s and 50s. Some of them spanned multiple regions, reaching the numbers required to be declared a "plague".

Overall, the FAO estimates the desert locust affects the livelihood of one in 10 people on the planet - making it the world's most dangerous migratory pest.

| Year | Recession | Upsurge or decline | Plague |

| 2019 | 0 | 18 | 0 |

| 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 2014 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 2013 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 2012 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 2011 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 2010 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 2009 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 2008 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 2007 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| 2006 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2005 | 0 | 20 | 0 |

| 2004 | 0 | 23 | 0 |

| 2003 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 2002 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2001 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2000 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 1999 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 1998 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 1997 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| 1996 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| 1995 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| 1994 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| 1993 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| 1992 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 1991 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1990 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 1989 | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| 1988 | 0 | 0 | 26 |

| 1987 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| 1986 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| 1985 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 1984 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1983 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 1982 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 1981 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 1980 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 1979 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 1978 | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| 1977 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 1976 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 1975 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 1974 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1973 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 1972 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 1971 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 1970 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 1969 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| 1968 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| 1967 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 1966 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 1965 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 1964 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 1963 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| 1962 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| 1961 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| 1960 | 0 | 0 | 44 |

| 1959 | 0 | 0 | 47 |

| 1958 | 0 | 0 | 41 |

| 1957 | 0 | 0 | 37 |

| 1956 | 0 | 0 | 35 |

| 1955 | 0 | 0 | 43 |

| 1954 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| 1953 | 0 | 0 | 43 |

| 1952 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| 1951 | 0 | 41 | 0 |

| 1950 | 0 | 33 | 0 |

| 1949 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 1948 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| 1947 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| 1946 | 0 | 36 | 0 |

| 1945 | 0 | 0 | 42 |

| 1944 | 0 | 0 | 47 |

| 1943 | 0 | 0 | 43 |

| 1942 | 0 | 0 | 35 |

| 1941 | 0 | 24 | 0 |

| 1940 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 1939 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 1938 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 1937 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 1936 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 1935 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 1934 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| 1933 | 0 | 18 | 0 |

| 1932 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| 1931 | 0 | 0 | 35 |

| 1930 | 0 | 0 | 45 |

| 1929 | 0 | 0 | 41 |

| 1928 | 0 | 0 | 34 |

| 1927 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| 1926 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Source: FAO | |||

| Note: Recession means locusts are present at low density; upsurge means several locust outbreaks have accelerated through breeding; a plague means widespread and heavy infestations for more than a year; the end of a plague is called a decline. | |||

New swarms of locusts are developing

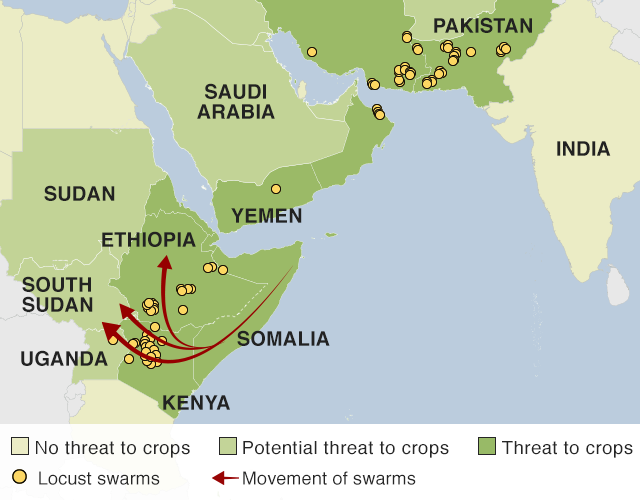

Earlier this year, the worst swarms of desert locusts in decades decimated crops and pasture across East Africa and beyond, threatening the food security of the entire sub-region.

The ravenous insects spread rapidly in January and February through a number of countries in East Africa - including Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia - as well as areas of Pakistan. It became the worst infestation in Kenya for 70 years and the worst in Somalia and Ethiopia for 25.

The FAO now fears that favourable wet weather in March and beyond will lead to a second wave of swarms posing an "unprecidented threat" to livelihoods once again.

Insect numbers could grow another 20 times, the FAO warns, unless control activities are stepped up.

A number of countries are on locust alert

This could be particularly devastating in East Africa - a region already suffering widespread food insecurity because of conflict, droughts and floods. But the situation is also worrying in Iran and Yemen, the FAO says, where new swarms are also developing.

Tens of thousands of hectares of croplands and pasture have already been damaged by locusts throughout East Africa.

At their peak earlier this year, swarms were eating 1.8m tonnes of vegetation a day across 350 sq km (135 sq miles), the FAO says.

The organisation believes one swarm in Kenya covered an area 40km by 60km (25 miles and 40 miles).

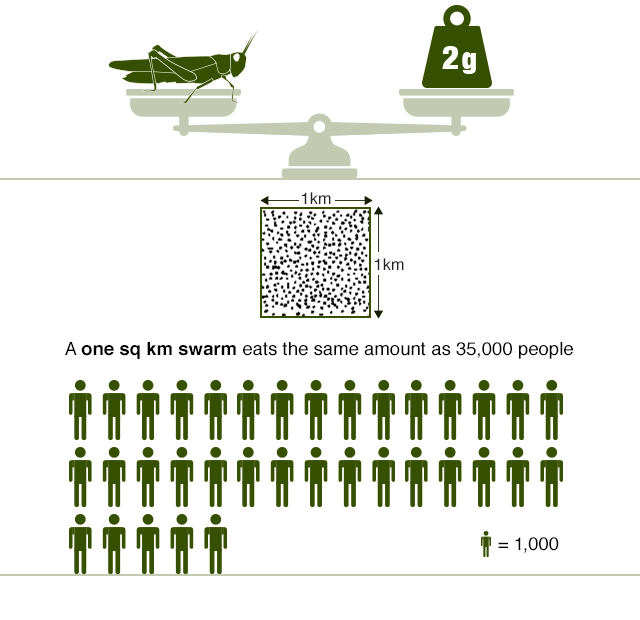

How much can a locust consume?

An adult desert locust can eat its own weight in food every day - about 2g Source: FAO

Source: FAO

The prospect of a new wave of locusts in Kenya and Ethiopia, possibly bigger than the first, is worrying in itself, but the timing couldn't be worse, says Keith Cressman, the FAO's senior locust forecasting officer.

"Now is the beginning of the rainy season in those countries and the beginning of planting. Seeds are germinating and they're sprouting and now you've got locust swarms."

These current maturing swarms will soon lay eggs that will produce another generation of locusts maturing around harvest time, Mr Cressman says, threatening crops twice.

The locust crisis also comes at a time when countries are dealing with a rise in coronavirus cases as well as the asssociated restrictions on movements, complicating control operations.

Ali Bila Waqo, a 68-year-old farmer working in north-eastern Kenya, was one of those affected by the recent swarms. He was hopeful of a good grain harvest this season, with recent rainfall ending a long period of drought.

But locusts destroyed all his maize and beans in February.

"They ate most of our grains and what they didn't eat, dried up," he says. "That has hurt us a lot. We saw the food with our eyes but we never even got to enjoy it."

Mr Waqo, who remembers a previous locust infestation in the 1960s, describes how the swarms blacken the skies.

"It gets dark and you can't even see the sun," he says.

Extreme weather has fuelled the crisis

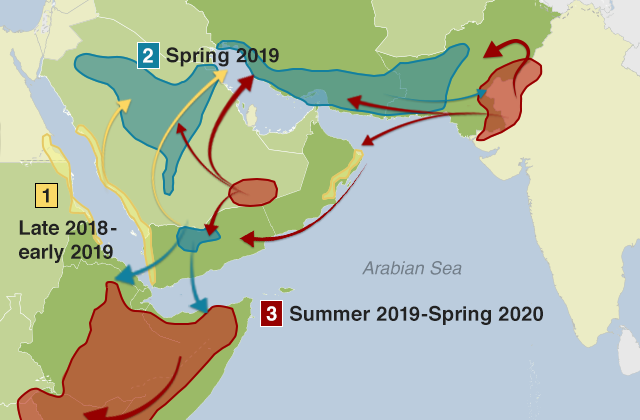

The causes of the current infestation go back to the cyclones and heavy rains of 2018-19.

Desert locusts typically live in the arid areas of about 30 countries between West Africa and India – a region of about 16 million sq km (6.2 million sq miles).

But the wet, favourable conditions two years ago on the southern Arabian Peninsula allowed three generations of locusts to flourish undetected, the UN says.

The upsurge has been developing since 2018

By early 2019, the first swarms headed to Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Iran, breeding further before moving to East Africa.

Further swarms formed and by the end of last year had developed in Eritrea, Djibouti and Kenya.

Spring breeding is now expected to cause further infestations in East Africa, Yemen and southern Iran in coming months.

Even though such infestations are notoriously hard to battle because of the wide geographical area affected, the FAO's Mr Cressman believes more could have been done earlier to tackle this particular locust upsurge.

"If there were greater and more successful efforts of control made in some of the key countries, it might have minimised the situation," he said.

People are trying to tackle the huge swarms

With the locust swarms in East Africa unprecedented in terms of their size and destructive potential, countries are scrambling to deal with them.

Containment of the outbreak depends on two major factors - monitoring and effective control.

The Desert Locust Information Service, run by the FAO, provides forecasts, early warning and alerts on the timing, scale and location of invasions and breeding.

But once populations reach critical levels, such as in East Africa, urgent action needs to be taken to reduce locust populations, as well as prevent more swarms from forming and spreading.

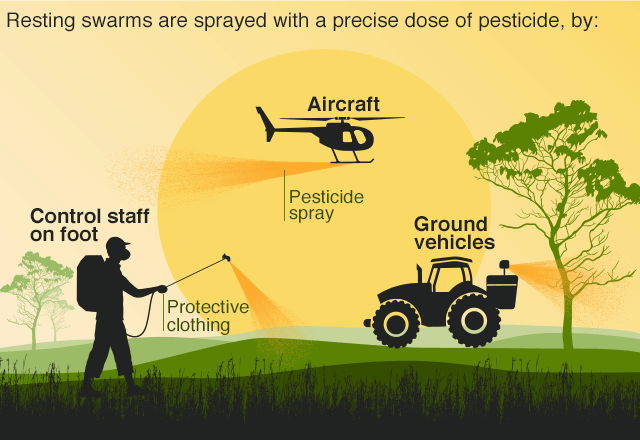

How locust swarms are tackled

Source: FAO

Source: FAO

Although there is ongoing research into more environment-friendly solutions, such as biological pesticides or introducing natural predators, the most commonly used control method is pesticide spray.

Showered onto the pests via hand pumps, land vehicles or aircraft, whole swarms can be targeted and killed with chemicals in a relatively short period of time.

For this reason, the FAO is currently working with governments to carry out a number of aerial pesticide spraying campaigns.

So far, more than 240,000 hectares across 10 countries have been treated and hundreds of people have been trained to carry out ground operations.

The campaign is much more efficient than it was earlier in the year, Mr Cressman says, and restrictions on movements caused by coronavirus have not hampered operations to any significant extent.

But controlling such large populations of insects over large, remote areas remains a logistical challenge. You never really know what percentage of the locust population you have successfully targetted, explains Mr Cressman.

But action taken now will determine what happens next. If the current upsurge crosses more borders and infests more regions, devastating more crops, it could be declared a "plague".

For this reason it crucial to "join hands and share knowledge and skills" to prevent further deterioration of the situation, Mr Cressman adds.

Yet, for Kenyan farmer Ali Bila Waqo, such action comes too late. The only thing he and his family could do to battle the pests when they descended was to bang on jerrycans and shout.

Yet, he remains philosophical about what has happened.

"It is God's will. This is his army," he says.

Credits

Words and production by Lucy Rodgers, field production by Joe Inwood, design by Zoe Bartholomew and Millie Wachira, development by Becky Rush, Catriona Morrison and Purity Birir. Locust images by Swidbert R Ott and Stephen Rogers and Getty Images. Kenya farming images by the �鶹��.

Hundreds of billions of locusts swarm in East Africa

Hundreds of billions of locusts swarm in East Africa

Locusts add to food security concerns

Locusts add to food security concerns

UN warning for Ethiopia, Kenya, Eritrea and Sudan

UN warning for Ethiopia, Kenya, Eritrea and Sudan