�鶹�� broadcasts in Polish began on 7 September 1939, a week after Germany invaded and ten days before Soviet Union forces launched their attack. Occupied in little over a month, the �鶹�� initially spoke for a nation unable to speak for itself. And over the coming years of World War and Cold War, the �鶹�� saw itself as having a special role: to broadcast in the interests of the Polish people.

Forty years later, in 1979, the �鶹�� were surprised to be given permission by the Polish authorities to hold an exhibition in Warsaw’s Victory Square to commemorate the wartime role of the �鶹�� Polish Section. This was to be the �鶹��’s first exhibition behind the Iron Curtain and indicated, initially at least, a thawing of Cold War relations, with a public display including a German ENIGMA encryption device smuggled out by Polish intelligence and deciphered at Bletchley Park.

For the �鶹��’s Head of Central European Services, Noel Clark, it was also an opportunity to showcase the �鶹�� in a contemporary context. But the night before the opening, as Clark recalls in this interview for the �鶹�� Oral History Collection, problems started emerge.

The public response to the exhibition’s cancellation, as Clark reports, indicated the close bond that still existed between the broadcaster and its Polish audience. It also indicates governing anxieties about the continuing influence of the �鶹�� inside Poland. As the British Embassy in Warsaw had enviously noted in February 1979, “the value of the �鶹�� is infinitely greater than Embassy information work”.

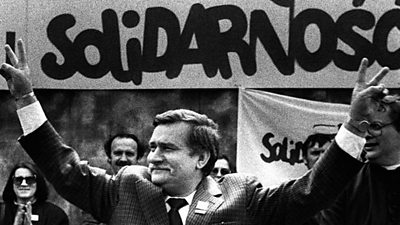

At the same time, the Polish authorities were coming under intense public pressure for political and social reform after three decades of communist rule. A general economic decline was accompanied by increasing industrial action, and by 1980 a wave of strikes, including those led by the electrician Lech Walesa at the Lenin Shipyard at Gdansk, brought Poland to the point of crisis. This culminated in the August 1980 Gdansk Agreement whereby the Polish government agreed to a number of the strikers demands, including the right to form a non-governmental Trades Union: Solidarnosc.

Meanwhile, a new generation of émigré broadcasters who had grown up under communist rule in Poland arrived at the �鶹�� after the protests that had swept across the continent in 1968 and the purges that followed in Central and Eastern Europe.

First among these was Kris Pszenicki who quickly realised that the editorial style of the �鶹�� Polish Section needed updating. As he later put it, “It took time before some “old-timers” were persuaded that linguistic norms were coined on the Vistula, not in the vicinity of the Thames”. By the start of the 1980s, however, the Polish Section, now led by Pszenicki, was transforming itself into an agile and innovative broadcasting unit.

As the Solidarity movement grew, reaching a peak of around nine million members, speculation mounted about what the Polish government would do to reassert its control over Polish society. The answer, announced by Prime Minister General WojciechJaruzelskion Sunday 13 December 1981, was the declaration of Martial Law, involving the extensive use of censorship, the rounding up of thousands of Solidarity supporters and the shooting of demonstrators.

At the �鶹��, as Noel Clark recalls, news of this development produced a flurry of activity at Bush House, the home of the �鶹�� External Services, as the World Service was then known.

As intended, Martial Law made it extremely difficult to get up-to-date news from inside Poland out to the rest of the world. However, in this respect, the �鶹�� had three significant advantages. The first came as somewhat of a surprise to the assistant head of the �鶹�� Polish Section, Eugeniusz Smolar, one of the new generation of Polish broadcasters, who in this new oral history interview reveals how the �鶹�� outwitted Polish censors.

The delight at discovering an alternative international telephone line into Poland, via Istanbul, which hadn’t been shut down under Martial Law was matched by an equally improbable development at the Polish Academy of Sciences. For Smolar, this began with being summoned to the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall.

The Istanbul telephone line and the IBM computer link provided the Polish Section of the �鶹�� with vital insights into the unfolding events inside Poland, which were reflected in broadcast output. However, this technological good-fortune was underwritten by the personal relations of some �鶹�� Polish staff with leading figures in the Polish opposition movement who they had been to school and university with and protested with, before leaving Poland.

These connections were known to some of the managers in Bush House and there were obvious editorial concerns about the risk of manipulation and bias in Polish programme output. However, as Noel Clark, who observed this closely at the time, later noted, “the �鶹�� was never let down” by its Polish staff.

"the younger ones who I felt perhaps most uneasy about at the beginning, had lived themselves in Poland, in a Communist society, knew what it meant to be able to listen to the �鶹��, an unbiased impartial source of straight news. And they knew that above all the �鶹��’s credibility was our most precious asset in Poland, and therefore they were every bit as eager and far better qualified perhaps to judge than myself, than I was, what was reliable information emanating from Poland."

The activities of the �鶹�� Polish Section were not confined to Bush House, however, and the Smolars’ home telephone became a conduit that carried information from reform organisations in Poland such as KOR and Solidarity, to the outside world. Recording, transcribing and publishing this information became a considerable task in its own right, involving a number of �鶹�� Polish staff, outside of their �鶹�� working hours.

This culminated in the regular publication of the Uncensored Poland News Bulletin between 1980-89, edited by Kris Pszenicki. Published under the auspices of the Information Centre of Polish Affairs, a charity run by former members of the Polish Section, Smolar describes it as “the most authoritative source”on events in Poland in the 1980s.

Crucial to the significance and appeal of this publication was the application of �鶹�� editorial values, such as balance, in its preparation. It became a vital source of Polish news for governments around the world, including Britain and America, civil society groups, trades unions and universities who took up subscriptions to get the inside story on events in Poland and the evolution of the Solidarity movement.

In 1982, Solidarity was officially banned by the Polish government and although Martial Law came to an end the following year, the Solidarity movement continued as an underground opposition movement, with broad appeal in Polish society.

The ascent of the reformist Mikhail Gorbachev to the leadership of the Soviet Union in 1985 and the continuing decline of the Polish economy created the conditions, by 1989, for the Polish Round Table Talks which led to the end of communist rule in Poland and Solidarity as the dominant party of power.

Reflecting on these radical changes, foreshadowing the collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe in 1989, Eugeniusz Smolar, then the head of the �鶹�� Polish Section, considers the contribution of the �鶹��. For him, Polish Section broadcasts presented listeners in Poland with an alternative: they reflected the “pluralism in Polish public life” and were a source of information that people could trust.

Written by Dr. Alban Webb, University of Sussex.