Parents naturally want to protect their children and will often keep from them difficulties they are going through in their own lives… Particularly, it seems, when they are dealing with their own mental health battles. However, for Joe Wicks, this silence, and not knowing, only made it more difficult for him to cope as a child.

In Joe Wicks: Facing My Childhood, Joe reflects on his relationships with his parents, who both suffered with severe mental health issues

Joe Wicks:

I was really not ready for this wave of emotion and gratitude that came through.

Aw, someone's knitted me, look. It's got all the big curly hair and the beard.

But the one thing I never expected, was that so many of the mums and dads who took part with their kids would start contacting me - not about their physical health, but about their mental health.

"Dear Joe, for many reasons I've struggled with my mental health over the past few years… my son's father has mental health, as well as addiction issues… I suffer with very low self-esteem and confidence, and felt really depressed… as a mid-40s woman, who suffers with anxiety and depression…"

Again the words that keep popping up - it's just literally anxiety, depression, anxiety, depression so much of it. You can't process that, you can't just go "oh that's another one, thanks!" Like it's, every single one of these stories is a real person.

The thing is, I do relate to it. My mum and dad were up and down, up and down, all my life. My mum had severe OCD and my dad was in and out of rehab - like, it was madness. I remember sort of being a child and just being like so upset and confused and lost. It was really tough, and then when I read these letters from parents that are saying that they're going through similar mental health issues, I can't help but feel a connection.

I worry about what impact parents' mental health is having on kids, about how my own childhood has affected me.

It comes in waves, some days I'm like, "I really love this", other days I just want it to stop, I don't want to be the 'body coach', I just want to be Joe. I don't want to have to carry all these emotions and stuff, it's like I'm just in the middle of it all, aren't I? It's just like this is what I do, but it does, it must, affect me more than I think.

“My mum and dad were up and down, up and down all my life. My mum had severe OCD and my dad was in and out of rehab - it was madness. I remember being the child in that scenario, and just being so upset and confused and lost. It was really tough.”

Joe Wicks

Although best known for getting the country exercising over lockdown, Joe has other goals - one of these is to encourage parents who are suffering with their mental health to be open with their children. In his documentary, Joe Wicks: Facing My Childhood, Joe speaks to others who have had similar experiences to his own.

During the documentary, Joe met Dympna Cunnane, psychologist and Chief Executive Officer of Our Time, a charity which supports children who have a parent with a mental illness.

She’s seen how parents facing difficulties with their own mental health can find it difficult to share this with their kids. “It’s often the case that parents have never spoken [about it] to their children. And it's that silence that leaves both parents and children struggling alone."

Dympna spoke to the Parents' Toolkit about the positives that can come from being open with your child as well as giving advice on how best to have these conversations.

Why parents keep quiet

Not talking about mental illness can be the default for many families, like it was for Joe’s…

“Talking openly about your problem seems such an obvious and simple thing for families to do. But it's definitely something that never happened in our house.”

Joe Wicks

“There’s a lot of stigma about mental illness so parents often feel embarrassed and ashamed,” says Dympna. “They keep it to themselves because they are concerned that the child might also be ashamed and embarrassed about the illness.”

Dympna says that often parents aren’t speaking in an attempt to protect their children, but she thinks that this can make things worse, not better.

The side effects of silence

“By not talking about it, it leaves the child feeling confused and scared,” says Dympna. “Sometimes they might feel responsible for not being able to make their parent happy.”

Not speaking to a child about mental illness doesn’t mean they won’t be exposed to it, explains Dympna: "When parents don't communicate, the children are left alone to understand what's going on around them. Without a conversation explaining what’s happening, it becomes a kind of secret, but it's not as if it goes away.”

That’s how Joe felt…

“I think the worst thing as a kid is that you feel like it's your fault. You feel like you're to blame or that you're not worth enough. Or that your parents don't love you enough. And those feelings are hardcore man. You can't carry them as a kid.”

Joe Wicks

Child-friendly ways to talk

The idea of talking to your child about your mental health can be daunting. Dympna has seen how parents themselves don’t often have a language, other than using medical diagnosis terms, with which to explain things to their children.

She has advice on how make these topics suitable for younger children…

At the very early ages, you're really talking about feelings and moods - like happiness and sadness - which children understand very well.

If your child is upset or worrying, it is best to listen to their concerns and explain in plain, child-friendly language rather than the language of mental illness which could increase their worries.

It’s important that these conversations go two ways - you want an open channel so your child can share their feelings too.

You can use stories, books, cartoons, which are age-appropriate and easily accessible, to help you open up the conversation with your child.

As your child gets older, Dympna explains that you can gradually introduce more complicated language to explain how your illness affects you and may change your behaviour, emphasising that it’s not their fault or their responsibility to make you better.

They might also hear things on the playground about mental illness that they don't understand,” she continues. “It will be helpful for you to give them a good explanation so that they can challenge any myths and stereotypes that arise. In this way the child can feel confident about their own understanding and possibly help others to be more sympathetic.”

“Tłó±đ˛Ô, as they get to teenage years, they need more hard information about how the brain works, what anxiety is,” says Dympna. “They will Google anyway, so for the parent, it's about being ready for that.”

Having that first conversation

It’s a good idea to plan when, where and how you’re going to have these conversations, says Dympna.

“Think about how you're going to do it. Think about your language. Think about what might be the best moment. The right moment will come if you've thought about it. And I think most parents know that there are bad moments and good moments.”

If you or your child are distressed, that may not be the right time, they might simply need reassurance until they feel better. “Find a quiet moment to do it where there's a sense of connectedness.”

You don’t need to do this alone. Dympna says it can be useful for another family member or family friend to be there. Letting your child know that they can mention what’s happening to another adult is important too: “One of the most important things is that the child doesn't become isolated and has another trusted adult to talk to.”

Sharing is important, but boundaries are vital. “I think it's really important that you think about when you share the information and the level of which you share it. You don't need to give all the personal details.” She adds, “With oversharing you risk passing the burden onto them.”

The benefits of talking

Dympna has seen first-hand the positives from having these conversations. “What we hear from the children who are in our workshops is for the first time somebody is actually talking to them about this thing that they know is there, but they haven't been allowed to speak about it. It’s such a relief. They don't feel responsible anymore for their parents’ bad mood.

“When somebody does talk to them, whether it's an ill parent or a well parent, then the child can cope better with the changes in the parents' mood or behaviour because they understand it as an illness rather than as the parents being angry with them.”

She explains that this can improve relationships: “They develop sympathy for the parent, rather than fear and anger."

Continuing conversations

Once you’ve had that first conversation, Dympna explains that these chats can just become another part of normal life.

“I think that's about the continuing conversation. It's like anything else in the family that needs to be talked about over and over again, this is one of them. It's important that the communication channel is available and open.”

Joe is hopeful that by having these conversations, parents across the country can make a real impact…

“We can't always stop parents from struggling with their mental health, but we can try to prevent the kids from ever having those feelings of confusion and anxiety that mental illness can create. And we can do that by learning to communicate with each other better.”

Joe Wicks

Parents’ Toolkit and commissioned a survey which spoke to over 2000 parents of primary children about attitudes and experiences of mental health in 2022. It found that parents have been experiencing a sense of uncertainty that hasn’t gone away and some faced challenges which they say could have impacted their child’s mental health. Read more here…

Speaking to Â鶹Éç's Tiny Happy People - Joe Wicks shares his thoughts on parenting, baby number four, big families and being a partner.

More from Â鶹Éç Bitesize Parents' Toolkit…

Parents' Toolkit

Fun activities, real-life stories, wellbeing support and loads of helpful advice - we're here for you and your child.

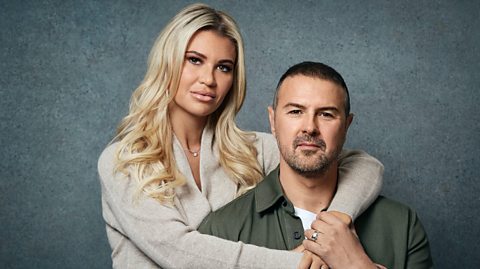

Paddy & Christine McGuinness - Our Family and Autism: Advice for parents

Paddy and Christine McGuinness have 3 autistic children - their experiences may help parents who're looking for, or have received, an autism diagnosis for their child

Roman Kemp: The Fight for Young Lives - mental health tips for parents

An exclusive film for Parents' Toolkit sees Roman Kemp remember how his mental health dipped in his school years and sharing the signs he observed and how he talked to his parents about his struggles. Two mental health experts offer additional advice.

Mental health first aid kit for parents: Who to ask and what to do

Worried that your child needs help with their mental health? Here's how you can access professional help and support your child while you wait.

Child mental health: Parents have their say

How do parents feel about mental health in 2022? Read about the results of our survey, in partnership with Netmums, here...

How to get your kids back out there and thriving after two years of lockdowns and isolation

YoungMinds have some tips to help you help your child get back out there doing the things they love post-pandemic.